"Queen of Stars" by Bryn Sparks

"Whether to Go Through" by Christopher Rowe

"Cerbo en Vitra ujo" by Mary Robinette Kowal

"Cut and Paste" by Peter Gutiérrez

"The Deep Misanthropic Principle" by Brandon Alspaugh

"Temple Part II: A Map of You" by Steven Savile

"Indigestion" by Robby Sparks

"Indigestion" by Robby Sparks

"Only an Echo" by Michael C. Reed

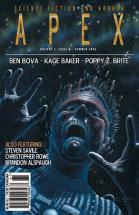

Ben Bova’s “Duel in the Somme” leads off issue #6 of Apex Digest with an aerial combat tale. Sort of. Tom Zepopolis is a self-professed geek working in the advanced projects department at his design company. Tom and his supervisor, a rather large jerk-of-a-fellow named Kelso, both have designs on Lorraine, the office hottie. Not only is she beautiful, but she’s bright as well. All of this leads to a duel in the skies in World War One biplanes/triplanes. Except it’s all simulated in the company’s VR lab, both men goggled and gloved. The loser agrees to stop pursuing Lorraine.

I really liked this brisk little tale. In the Author’s Note at the end, Bova say that this story was inspired by “The Perfect Warrior,” which was published in 1963. I’m not sure when he wrote this story, but by today’s standards it’s really not science fiction. Everything in this story is possible today, or will be the day after tomorrow, so there really isn’t any speculation to it. But that hardly matters. As always, Bova’s lucid prose is quite readable, and his characters are well-drawn. Read it and find out who “dies” in the skies, and who gets the girl. In the end, it’s not winner take all as Tom and Kelso agreed upon.

“Queen of Stars” by Bryn Sparks is an enjoyable high-tech adventure set in deep space. Moesha and her lover Aaron are the only crew aboard their massive stellar-sailed vessel currently in the Jovian system. Wanting to test her latest pair of high-tech stiletto footwear she’s designed and built, she dons her nanotech space suit and ventures outside onto the hull of their ship. But soon pirates arrive, breach the hull, and rape and murder Aaron, leaving Moesha stuck outside to deal with her predicament and the loss of her lover.

What could have been a run-of-the-mill adventure story is strengthened greatly by two things. First, Sparks’s use of detailed imagery is quite good: from the black nan-suit that Moesha sprays on her body, a second skin that exists somewhere between organic and inorganic, to the grisly depiction of the space pirates who devour Aaron. The author barely describes the death of Moesha’s lover, but because he depicted the pirates so well before the foul deed is committed, he doesn’t need to. And all this is seen by Moesha on the outside of the ship through the aid of the nan-suit which interfaces her brain with her ship’s systems within. I found this a clever storytelling device for this first-person narrative, allowing the protag to be wherever she needs to be to tell the tale.

The second notable quality lifting this story above sheer action and adventure is rather difficult to discuss without giving away the ending. But just let me say that it is a transcendence-type denouement that elevates this story above the mundane win, lose, or draw resolution. Oh, Moesha’s high-tech footwear comes to her aid as well. Hell hath no fury like a woman’s stiletto!

In Christopher Rowe’s “Whether to Go Through,” three spacemen, who are twenty-two days from establishing a Jovian orbit, suddenly find themselves in a strange, hot room. Instantly, they are terrified and try using all their training to ascertain their dire situation. One of them, Flaherty, dies from his fall and exposure, while the other two, Burton and Doyle, carry his body to keep it from burning on the hot floor. On the wall is a strange light that they assume is a doorway. The room is so inhospitable they know that they must go through. What will they do?

That’s the basic plot of this short-short that I would categorize as a "problem" story. It’s really not a character-driven tale, as these three spacemen are rather interchangeable and the tale is too short to get to know them, though I did feel their terror. This is a savage little piece, but in the end it leaves open more questions than it even hints at answering. Which is the point, I think.

“Cerbo en Vitra ujo” by Mary Robinette Kowal takes place within a series of orbital worlds and involves the young Grete’s search for her boyfriend, Kaj. Supposedly, Kaj is going away to school, but soon Grete finds out that is not the case. Kaj, like all third children of their parents and beyond, is an illigit, and such children must be careful so the organ harvesters don’t get them and sell their much-in-demand body parts, which, to her terror, Grete discovers has happened to her boyfriend.

This tale moves quickly as she first finds a woman wearing Kaj’s eyes, and then a pianist at Doc’s Piano Bar possessing his hands as well as another choice member of the handsome young man’s anatomy. Although I did see much of this coming, especially when Kaj’s other illigit siblings haven’t been seen in a while, Kowal does know how to tell a gripping tale, blending sex and violence to an exciting conclusion. While normally predictability would be a big drawback to a story, I wasn’t disappointed. Here, superior writing ability won me over.

Peter Gutiérrez’s “Cut and Paste” is an odd piece. Though it has a unique idea at its core, I found it a very frustrating read. I read it three times and I’m not sure I really got it. It appears that we have been invaded by our own alphabet by some unknown force. Whether this invasion force is your standard alien fare or the post-human singularity, I’m not quite sure. Neither of these is mentioned. The story’s narrator certainly isn’t much help. The rebels, as he calls them, have allowed him to be their spokesman, which means he and he alone is allowed the use of language in print. I do think this is rather the point and purpose behind the difficult prose that meanders throughout the story in true orbicular, academic fashion, telling this tale in vague abstractions. This is a plotless story written in the form of an essay. There are no characters except the nameless narrator and “the rebels.” The old writer’s saw “show don’t tell” is certainly turned on its head here. This is all telling and precious little showing. And for the most part, the telling is written by a narrator who is purposely trying to cloak his meaning in the ambiguity of cryptic words designed so as not to offend “his masters.” Or the entire story is nothing but “show,” meaning each word, each phoneme, each letter on the page is a opportunity for the reader to look the invasion force squarely in the eye. Know your enemy! Yes, not only was this one difficult to read, but very difficult to interpret. Even more difficult was it to convey to you, the reader, in the form of this story’s insidious enemy: the written word.

“The Deep Misanthropic Principle” by Brandon Alspaugh is a hard science fiction/horror tale that combines quantum mechanics, religion and, yes, monsters. It takes place aboard the generational starship the Pistis, where young protagonist Sophia, her mate, Philip, and the rest of the students are in informational quarantine. Below in the hold of the ship are creatures known as Fugues, hideous beings who were once human but underwent metamorphosis due to informational overload back in 2017 on Earth when human knowledge began doubling every minute. So why bring them along if that’s what they are fleeing? Well, that’s what this tale is about.

The story opens with their classmate Eve’s death, and Sophia and Philip boldly venture to the hold of the ship because the answer to her death may lie there with the Fugues. This was not the easiest tale to read, but if one reads carefully, the author’s intent does become apparent. I feel for the reader who doesn’t possess the requisite cutting-edge SF knowledge to make sense of this story. Although hard science fiction isn’t my bailiwick, I do consider myself well read in it enough to grasp most of the concepts here. Still, I found it a chore. Readers of the more theoretical SF found in Analog shouldn’t have any trouble with it. But it does make me wonder if the recent decline of science fiction in favor of fantasy has much to do with esoteric stories such as these. Yes, it’s important to push the genre toward a new future. But in the process I wonder if we’re leaving all but a few dedicated, zealous readers in our wake. For that is the true definition of the word esoteric, meaning: only for the initiated.

I always like to read a new writer’s first published story, and “Indigestion” by Robby Sparks is an entertaining one. In this alien-encounter tale, Hardin is a “presenter,” a lecturer of sorts who has been trained to perform this task since he was five when he was taken from his parents. Basically, he’s a slave to his Superiors. But Hardin has a plan to escape. While visiting off-world, a Girobian scientist gives him a serum to drink that when flushed from his bowels into Earthbase IV’s toilet facilities, will work its way into the water supply rendering his human captors unconscious, thus allowing him to escape. But the Girobians have an ulterior motive. Not only does the serum render the humans unconscious, it turns them into these strange piglike creatures that the Girobians not only carry their currency in (giving a whole new meaning to the term "piggybank"), but these creatures actually produce their currency in their digestive tract as well.

Pretty unbelievable, huh? Of course, but this is burlesque SF and it works! And it works because, though outrageous, it never crosses over to becoming blatantly absurd. On some level, this story takes itself seriously. Though you know that all this is impossible within the confines of reality, you do feel Hardin’s dire situation as the humor is kept to a minimum. I did find this story rather long at the upper length of a short story, nearly becoming a novelette, which is something Sparks can work on in the future. But he has the storytelling aspect down, and compression of style is something that can be learned with practice. Yes, this tale was ridiculous, and thoroughly enjoyable!

“Only an Echo” by Michael C. Reed is a slippery flash fiction piece with an SF bent. Peter and the little Jesus are sentient simulacra, placed near the water by what I’m assuming is some sort of odd nativity scene. All manner of newsprint, rotting food, and other debris clutter the scene. Not much of a plot here, but there is a tragic little moment at the end that mirrors the crucifixion. I’ll leave it to each reader to come to his or her own conclusion. It’s one of those open to personal interpretation.

In addition, this issue of Apex includes the second part of a four part serial by Steve Savile, “Temple Part II: A Map of You"