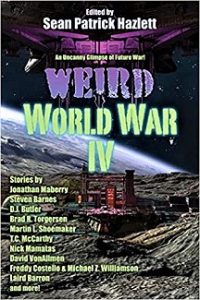

Edited

by

Sean Patrick Hazlett

(Baen Books, March 2022, tpb, 352 pp.)

“Deep Trouble” by Jonathan Maberry

“The Big Whimper (The Further Adventurers of Rex, Two Million CE)” by Laird Barron

“Reflections in Lizard-Time” by Brian Trent

“The Transformation Problem” by Nick Mamatas

“Triplicate” by Freddy Costello and Michael Z. Williamson

“We Are Not Monsters” by Steven Barnes

“Twilight of the God Makers” by Erica L. Satifka

“Portals of the Past” by Kevin Andrew Murphy

“The Door of Return” by Maurice Broaddus and Rodney Carlstrom

“An Offering the King Makes” by D.J. Butler

“A Line in the Stars” by Martin L. Shoemaker

“Astral Soldier” by David VonAllmen

“Chaos Redeemed” by Deborah A. Wolf

“Mea Kaua” by Stephen Lawson

“Wave Forms” by Nina Kiriki Hoffman

“Lupus Belli” by Julie Frost

“Ancient-Enemy” by Eric James Stone

“Blue Kachina” by T.C. McCarthy

“The Eureka Alternative” by Brad R. Torgersen

“A Day in the Life of a Suicide Geomancer” by Weston Ochse

“Future and Once” by John Langan

Reviewed by Victoria Silverwolf

All of the stories in this anthology take place during some kind of conflict that follows a Third World War. Although this might seem to be a limited theme, the various authors have risen to the challenge, and produced a wide variety of fiction incorporating science fiction and fantasy concepts into tales of struggles that do not always take place on battlefields.

The narrator of “Deep Trouble” by Jonathan Maberry gets involved in a secret project located at the most remote part of the Pacific Ocean, only because of an essay he wrote as a joke while a student. His tongue-in-cheek suggestion for what might be done under extreme circumstances turns out to be all too real, leading to extraordinary consequences for the entire world.

Without giving too much away, it should be said that this story depends on a famous concept from a noted writer of imaginative literature of the early twentieth century. Readers who are familiar with the works of this author will recognize this right away, and will not be surprised by the dramatic climax. Those who are not yet tried of the endless sequels and pastiches of the writer’s imagined universe will best enjoy this example, while others may find it overly familiar.

Written in a dense, difficult style, “The Big Whimper (The Further Adventures of Rex, Two Million CE)” by Laird Barron is hard to summarize. In brief, it features a greatly enhanced dog, partly mechanical, in the distant future, long after humanity has been replaced by a society of sentient ants. (This is also long after World War Three and an alien invasion, to add to the story’s complexity.) The dog encounters a strange being resembling a man, bringing the tale to an apocalyptic conclusion.

I have offered only a poor synopsis of this unique work, partly due to my failure to fully understand it. The brief description I have offered suggests that the author was influenced by Clifford Simak’s classic work City. It should be noted, however, that this variation on that award-winning book reads as if written by the most experimental New Wave authors of the late 1960s. In any case, it is certainly unusual, but may leave most readers scratching their heads.

“Reflections in Lizard-Time” by Brian Trent takes place when the Third World War is interrupted by the arrival of two different kinds of sentient reptiles from another plane of existence. The protagonist and a former enemy make an uneasy alliance with one of the two species, discovering why they came to this version of Earth and how it involves yet another race of beings.

The author manages to make the wild premise seem believable, and creates interesting non-human characters. The story is exciting and suspenseful, but it ends very suddenly with a major plot twist, almost as if it were the opening chapter of a novel.

The setting for “The Transformation Problem” by Nick Mamatas is a spaceship that left Earth for the far reaches of the solar system, in order to escape government oppression. The appearance in deep space of tiny black holes, combined with an anomaly in the ship’s artificial intelligence and conflict among the crewmembers, leads to a crisis.

There is a great deal of socioeconomic content to this story, which may have an influence on how readers respond to it. The narrative includes a reference to the granting of special rights to the incompetent and weak while robbing the productive members of society, which sounds like Ayn Rand style philosophy. On the other hand, the AI unexpectedly changes distribution of necessities on the ship according to the dictates of Karl Marx. The ending of the story seems to come out of nowhere, and the author’s intention escapes me.

“Triplicate” by Freddy Costello and Michael Z. Williamson is a satiric tale of a bureaucratic war in which Russians attempt to defeat an altered United States by dumping a huge amount of paperwork on them. The Americans fight back in a similar fashion.

Although the basic plot mocks red tape (and a sly reference to Eric Frank Russell’s Hugo-winning story “Allamagoosa” confirms this), much more of the story spoofs political correctness. This is a future world in which trees are known as Plant-Based Persons, as one small example. An important subplot involves the transformation of a nonbinary individual, using the pronoun “they,” into accepting her identity as female, after a romance with the male protagonist. How one feels about these kinds of issues is likely to influence how much one enjoys the nonstop lampooning of cultural liberalism. Regardless, the satire seems rather heavy-handed, particularly since the story is fairly long for a simple plot.

In “We Are Not Monsters” by Steven Barnes, a scholar attempts to warn the President of the United States that global interactions among gigantic corporations could result in the emergence of a new and dangerous entity. After his fears are dismissed by the government, he discovers that things have gone much farther than he expected, in a frightening way.

The plot builds slowly, from a quiet beginning to a truly terrifying climax. The author clearly worries about the power of international mega-corporations, so readers’ views of these organizations may determine their responses. In any case, this is an effective science fiction horror story.

“Twilight of the God Makers” by Erica L. Satifka features superpowered, winged humans created through genetic engineering, and grown in the wombs of ordinary women, who die when the enhanced beings burst out of their bodies. Formerly used as peacekeepers after a world war, they degenerated into demented monsters who attacked normal human beings. Government scientists continue to create new ones, who are kept in a maximum-security facility, in an attempt to solve the problem. When a violent superhuman escapes the prison, another who seems to be under control is sent to battle him.

Even if one accepts the fantastic premise, it is very hard to believe that a woman, out of patriotism, would be eager to sacrifice her life in such a horrible way. The plot depends on dozens, perhaps more, of such volunteers, which strains credibility. Aside from that, readers may enjoy the excitement of this very dark variation on superhero fiction.

The protagonist of “Portals of the Past” by Kevin Andrew Murphy is the semi-biological offspring of mechanical beings, living long after the Third World War. He encounters a woman from the past who takes him on a wild journey back and forth in time, as part of a struggle against other time travelers.

The author displays a great deal of imagination, and the story moves at a breakneck pace. For the most part, this is a love letter to San Francisco. To fully appreciate it, one should know quite a bit about the history of the city, from Spanish settlers to hippies. I found myself frequently interrupting my reading in order to find more information about the people and places mentioned in the text. This may be too much to ask of readers looking for a piece of entertainment.

In “The Door of No Return” by Maurice Broaddus and Rodney Carlstrom, an agent for a newly emerging African state uses magic to journey instantaneously through space, obtaining an ancient artifact of great power from a museum. With the help of a museum curator, he wages a battle against nations recovering from World War Three, that seek to seize the African continent for themselves.

The story is obviously an impassioned cry against the exploitation of African peoples, from slavery to the theft of artworks. As with many tales in this anthology, its welcome may depend on the reader’s attitude about the issues it raises. As a piece of fantasy adventure, it is entirely adequate. Some may think that it brings in too many supernatural elements, from the Shroud of Turin and numerous other artifacts to Lovecraftian nameless gods.

“An Offering the King Makes” by D.J. Butler takes place inside a computerized version of Egyptian mythology, somehow brought into being by a videogame genius. A team of soldiers, accompanied by a magician, battle monsters and parley with gods in order to defeat the self-appointed pharaoh who created the place. The war leads to an unexpected resolution.

I was never quite clear on how this virtual reality simulation interacted with the real world. The bloody deaths and bizarre transformations that occur seem to be actually happening, as far as I can tell. The story is an intriguing mixture of modern combat and ancient legends, if a little confusing.

The narrator of “A Line in the Stars” by Martin L. Shoemaker is a secret agent for a coalition of governments recovering from World War Three. The damaged Earth is dependent on the manufacturing done by orbiting space stations, even for such basic items as food. One of the stations has a secret supply of nuclear weapons, and is planning to use them on Earth. The narrator sneaks aboard a supposedly unmanned supply vessel in order to infiltrate the rebel station and stop their world-threatening scheme.

In essence, this is a high-tech spy story, something like James Bond in outer space. As such, it is reasonably tense, and holds the reader’s interest. How space stations are able to supply what the citizens of Earth need to survive is questionable. The narrator takes an unusual stance on the common libertarian theme of space travel being equivalent to freedom from government oversight, accepting the fact that bureaucrats and their regulations are inevitable, and not always a bad thing, if annoying. However, politics is not an important part of the story.

The title of “Astral Soldier” by David VonAllmen refers to a fighter who, due to the strange effects of a technologically advanced weapon, is able to project his soul outside his body. This makes him the perfect reconnaissance agent, as he can travel unseen into enemy territory. However, his body has to be protected by other soldiers while he journeys this way, even at the cost of their lives.

When a sneak attack kills his escorts, he has to proceed on his own, hiding his body while his soul finds a safe path, then going back into it so he can move his physical form out of danger. He discovers a secret enemy plot to make use of the technology that led to the power of astral projection, and must decide how to deal with the threat.

The fact that I felt a lengthy synopsis necessary may indicate that I found the premise intriguing and the plot compelling. In addition to this, the main character faces a crisis of conscience that makes this work emotionally powerful, and not just another war story.

The narrator of “Chaos Redeemed” by Deborah A. Wolf is a transhuman soldier, fighting a war against insurgents in Mexico, accompanied by an artificial intelligence inside her battle suit and a deadly, dog-like robot. A completely unknown animal destroys the enhanced (but not transhuman) soldiers at her side. Tracking down the seemingly impossible beast leads to an encounter with the supernatural.

Like some other stories in the book, this violent tale combines futuristic battleground technology with mythology. In this particular case, I found the blending of science fiction and fantasy slightly awkward. Given the setting, the reader may be able to predict the nature of the legendary creature. The fact that the devastation of a third world war is said to be due to the rantings of a “President Donaldson” may give a hint to the author’s political beliefs, but this is a minor part of the story.

“Mea Kaua” by Stephen Lawson takes place in a future of greatly transformed human beings, some able to fly and living in floating cities, others water-breathers dwelling in the depths of the ocean. When one of the airborne communities blocks out the sunlight that the sea people need for their underwater crops, the protagonist, a land-dweller, accepts a covert assignment to move the flying city out of the way. During his deadly mission, he rescues a winged woman from an attempted assault. They become allies, encountering both unexpected help and treachery.

The story is imaginative and full of violent action; perhaps too much for some tastes, with the hero slaughtering enemies left and right. The fact that this strange future world came about under the control of artificial intelligences after a devastating war, and that one of them is called Google, seems an unnecessary reference to the present in what is otherwise an exotic setting.

“Wave Forms” by Nina Kiriki Hoffman takes place in a near future when magic suddenly enters the world from nowhere, altering people in many different ways. Some become powerful wizards, others change into weird beings. (The premise reminds me of the “Wild Cards” series of superhero stories.) The narrator wakes up in a different body each day, which could be of any ethnicity, age, or sex. With the help of a woman who can transform herself into an unseen, ghost-like form, the narrator joins a group of rebels fighting to free their community from the dictatorship of a triumvirate of magicians.

Although it is not a comedy, the mood of this tale is much lighter than most others in the anthology, and might even be considered whimsical. The characters are appealing, but the plot ends just when the rebellion is about to begin. The story begs for a sequel, leaving the reader less than satisfied.

In “Lupus Belli” by Julie Frost, humans and werewolves fought a war, with the lycanthropes losing. The narrator was bitten by a werewolf during battle, and has become one himself, forced to live in the lycanthropic ghetto. After killing a pair of attackers in self-defense, he is sent to a prison for werewolves on the moon. Aliens attack the moon, killing the human guards and forcing the werewolves to choose between serving the invaders or fighting them.

The author combines two extraordinary premises, either one of which demands quite a bit of suspension of disbelief. The werewolves, with their various all-too-human quirks, are more interesting than the single-minded flesh-eating aliens, who seem to have stepped out of a comic book.

The title of “Ancient-Enemy” by Eric James Stone is the term used by Neanderthals, surviving underground for thousands of years, to refer to Homo sapiens. After a nuclear war between the USA and the USSR (which, in this alternate history story, takes place some time before the year 1992) the Neanderthals take several Soviets and an American woman prisoner.

The captives are used as slave labor, mining uranium ores to be used to produce nuclear weapons. This allows the Neanderthals to avoid radiation sickness caused by working in the mines themselves. After a battle to the death between one of the prisoners and a Neanderthal, with the Russian a predictable loser, the American proves to have a surprise for her captors.

The most interesting part of this story is the Neanderthal culture, with its many differences from that of Homo sapiens. The climax depends on the prisoners being able to perform a technological feat which seems very unlikely.

In “Blue Kachina” by T.C. McCarthy, two Native American astronauts land on an asteroid, considered to be within US territory, in order to find out what a Chinese spaceship is doing there. They discover the enemy’s motive, and the horrible fate they met. Meanwhile, one of the astronauts has multiple visions of people he knew on Earth, and undergoes a strange transformation.

This is an eerie, hallucinatory story, open to multiple interpretations. How one reacts to it may depend on whether one considers the events of the plot to be scientific or fantastic in nature. This ambiguity may puzzle readers.

“The Eureka Alternative” by Brad R. Torgersen takes place in a future United States losing a war with China. The US military, desperate to turn the tide of battle, makes use of advanced technology to send scouts to parallel worlds. Their hope is to find a plane of existence where America is winning, and make use of whatever advantages that alternate nation may have.

During one such experiment, a parallel version of one of the technicians shows up, as if this were her own world. The two duplicate women work together to complete the project, discovering an alternate plane that offers hope.

Although the idea of parallel worlds and duplicate people existing in them is hardly a new one, the author handles the theme well, managing the difficult task of making the two protagonists different enough to be distinguishable. The story’s resolution comes as something of a deus ex machina, but is interesting.

The narrative contains sufficient political content to make the author’s opinions clear, from disdain for so-called “woke” culture to a suggestion that California politicians might welcome Communist invaders. This is only a moderate portion of the story, but may put off some readers.

“A Day in the Life of a Suicide Geomancer” by Weston Ochse deals with a magical version of North America in the near future, in which various indigenous peoples battle their enemies, both sides using supernatural powers. The narrator undergoes a version of the Lakota Sun Dance, in an act of sacrifice against the black magic of the foe.

In sharp contrast to the previous story’s political stance, in this tale the forces of evil are based on a book said to be written by Donald Trump in the year 2030. Obviously, as with the prior work, this will turn some readers against the piece. Otherwise, this is a poetic, introspective tale, which should appeal most to those seeking a dream-like mood rather than an involved plot.

As a change of pace, “Future and Once” by John Langan is written as if it were a play, although some of the special effects required would greatly challenge any stage manager. It consists mostly of dialogue between the wizard Merlin, recently released from centuries of imprisonment within a tree stump, and a French soldier from the third world war. Merlin makes a prediction about her future, and the unlikely pair confronts one of King Arthur’s ancient enemies.

This twist on the legends of Camelot is most interesting for its dramatic structure, and would probably not be as intriguing in the form of a short story. The soldier’s fate will not surprise those familiar with Arthurian myth.

Victoria Silverwolf initially thought this was the fourth volume in a series of anthologies called Weird World War.