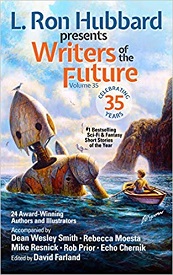

Writers of the Future, Vol. 35

Writers of the Future, Vol. 35

edited by

David Farland

(Galaxy Press, April 2019, pb, 450 pp.)

Reviewed by C. D. Lewis

The Writers of the Future Contest, as part of the contest award, publishes the three winners of each quarter in an annual Writers of the Future anthology. The contest considers both fantasy and science fiction. Since contestants and judges both change from year to year, the anthology includes a diverse range of works selected from a large applicant pool. In a multiple-author anthology, one frequently feels one’s chosen well if one can recommend one story in three; this volume beats that metric. As a result, it’s worth reading if you’re interested in speculative fiction: the quality and diversity assure one something will feel like a good match.

Applicants to the contest must not have had a professional fiction writing publication of a novel, or more than one novelette, or three short stories. Accordingly, the anthology represents the work of authors who haven’t been paid professional rates for more than a few short works. The anthology’s connection to the Estate of L. Ron Hubbard occasionally raises questions, largely because of awareness to the religion he founded. Contest applicants needn’t have a connection to the religion, the professional authors who judge works generally do not, and much of the praise one can find for the anthology over time comes from sources with no connection to the religion. Since the contest draws from around the world and publishes a dozen new works, it’s an interesting place to find new talent. Some, like Patrick Rothfuss and Brandon Sanderson, leverage success in the contest to get traction launching acclaimed works. It’s always fun to see a new star on the rise, and there are certainly some stars in this batch.

Elise Stephens’ “Untrained Luck” is a 10,000-word dystopian fantasy whose struggling protagonist, depressed following her sister’s death from a botched abortion, faces on-the-job manipulation by empaths while she works as a professional mediator in what turns out to be a drug turf conflict. In contrast to genre fiction’s urgent demand for an early hook and steady goal-oriented activity, Stephens’ entry has a more literary pace: a multi-day journey to a job site, seemingly-chance encounters while traveling by motorbike, the protagonist’s reflection on her situation and her ambitions. If you tolerate this pace, you may hang on long enough to enjoy the rich detail in Stephens’ harsh world. “Untrained Luck” launches several plot problems: the protagonist’s financial desperation, her professional ambitions as a mediator, her human desire to help an orphan she picks up at a fuel stop. Instead of intertwining the problems so they all resolve in a single high-stakes climax, “Untrained Luck” has them interfere with each other so they are resolved separately in different scenes. The decision takes the punch out of what might have been an explosive resolution. An ambivalent-feeling conclusion that opens the protagonist to an open-ended new problem with authorities certainly fits the dystopic setting. However, readers who demand a climactic resolution or an abrupt twist ending in their short fiction may not enjoy the result.

Kai Wolden’s “The First Warden” is a first-person fantasy short narrated by a newly-orphaned boy rescued by the mage who incinerated his village to contain a plague. It’s a dark open rich with possibility, and the world-building reveals so many conflicts one can hardly help anticipating the hard decisions the protagonist must make as conflicts brew between the orphan the clan leaders ordered killed, the leaders’ struggle to control the mage who spared him, and mounting tension with foreign refugees who turn out to fear and despise mages. While this happens the protagonist becomes emotionally entangled with a girl, is taken into the confidence of the village elders to keep an eye on the mage—so much is built up from which to construct conflict. Wolden uses a mythic-quality voice that conceals the years that pass while the mage raises his ward in a world that proves more and more complicated as the protagonist joins it. The anticipation is somewhat deflated when the “climax” turns out not to involve any of these things: the protagonist, upon discovering an orphan who is certainly a mage, decides to raise the child in the manner recommended by the mage who was the protagonist’s own self-appointed guardian. The scene that poses as a climax seems not to present the protagonist with a difficult, character-defining choice, but a choice that seems easy in light of his own upbringing and instruction. “The First Warden” shows a world that’s complex and exciting and no doubt full of stories, and it would be lovely to see one of those. This piece feels like a prologue to a work centered on the late-introduced mage whose origin story this work might be.

“The Damned Voyage” by John Haas opens on a walking-with-a-cane doctor accompanied by a giant armed-with-a-knife Indian servant dockside by a ship set to steam away with a cursed book that, even years after parting from it, still whispers to the protagonist’s mind. If you like steamer trunks and sword canes and mysticism and dark cults this could be for you. One soon wonders whether the protagonist is as dark as the foul cultists he seeks to oppose, and whether his commitment to protect the world from the cursed book will teeter and fail as he succumbs to its whispers. Haas eventually reveals a straight-up Lovecraftian horror, complete with sleeping elder things that dwarf the largest ship in the ocean. Horror lives or dies on the strength of the anticipation it can build, so it’s something of a triumph when Haas succeeds in building the stakes from mere death or madness to the obliteration of victims’ immortal souls. Extra points for not actually using the ship’s name, but planting enough clues for the reader to understand which famous doomed ship the protagonist boarded in search of the book.

Andrew Dykstal’s “Thanatos Drive” is a near-future SF adventure set in a post-apocalyptic world in whose protagonist bargains for gold and Advil in exchange for maps needed to help settle an old grudge. The imagined enemy is a networked population enhanced with medical cybernetics—but does the intelligence behind the world-ruining cataclysm even exist, any more? Dykstal spins a tale rich with technology, politics, historical detail, plausible puzzles, and believable characters. The story’s dark problem—two hunters pursuing for contrary reasons a single doctor who sells cures that risk turning patients into puppets of a neural network—is a dystopic delight. Fun reveals. Highly recommended.

In “A Harvest of Astronauts” Kyle Kirrin presents an outer space SF love story involving a character with an illness in love with an intelligent being comprising two bodies (both rented). It’s a strange and beautiful mashup of high tech and ancient religious belief, science and love, fact and miracle. Kirrin creates a sense of longing and heartache and hope that is beautiful to behold. Don’t miss.

Wulf Moon’s “Super-Duper Moongirl and the Amazing Moon Dawdler” is SF set on the moon, narrated by a child unable to breathe without a prosthetic, which takes the form of an AI-driven mechanical service animal. The narrator’s backstory is interesting: the sole survivor of a publicized school bombing became a successful social media professional and funded her way to the moon, where from the story’s opening curtain she is bullied by a botanist by whom she ultimately refuses to be cowed. The decisions surrounding her defense aren’t really hers: the hard choices are made by the AI driving her attitude-rich pet/prosthetic. Is the story hers, or the AI’s? Until the story’s main conflict is revealed, the piece has a travelogue feel best suited to people who want to tour a moon base. Near the end, the story’s central conflict becomes clear, but it may come a bit late to support the feeling that a story-sized plot arc has concluded. The narrator does eventually make a decision and a sacrifice, they feel they appear more in a denouement than the climax itself, but they nevertheless deliver a classic SF solution—creativity with tools and technology preventing a disaster threatened by forces too oblivious or uncaring to protect one human or her pet. The sacrifice and victory aren’t planet-sized issues, but their scale suits the lens of the child narrator. Everybody loves to see a bully served just desserts, and it’s a fun romp that concludes with clever smartasses getting one over on The Man.

Bestselling author Dean Wesley Smith is not published in this volume as a new contest winner (though his story is new), but a professional whose work appeared 35 years ago in Vol. 1 of Writers of the Future. “Lost Robot” is set in the universe of Smith’s Poker Boy and is narrated by his superhero private detective Sky Tate. Tate’s voice delivers a noir-ish salivation over her female client; the seeming coolness Tate projects belies her constant internal excitement. And it’s not because Tate’s a noob: her commentary reveals she’s hundreds of years old, able to read minds, and has made the acquaintance of divine beings. Tate’s incredible resources represent a running joke of endless deus ex machina solutions. Since Tate faces nothing that might look like risk, the story’s hook isn’t the protagonist’s sympathetic or frightening situation, but the outrageous solutions she directs at what can (by comparison) only laughingly be called a story “problem.” The climax is grounded not in some new conflict or hard choice, but in a reveal; its emotional energy flows from showing the client’s dying veteran father has something unexpected in common with his lost robot pal. The somber note in this lighthearted story’s climax is brightened by a denouement that returns Tate to her non-professional interest in her client. It’s a fun romp full of outrageous solutions.

Mica Scotti Kole’s “Are You The Life of the Party” is a revenge plot SF short. Since much of its force comes from reveals rather than plot arc, it’s challenging to discuss without spoiling it. The story’s scope does not embrace how the protagonist ended up operating a death trap maze or why the teens who bullied his daughter are subject to being released within it, but those details aren’t critical to the delight that fans of revenge-plots hopefully experience as the bullies’ character witness meets his fate. A revenge plot naturally excels in delivering a feeling of catharsis, and it’s engaging to watch a broken man take glee in doing horrible things to one who seems to have it coming; however, those who demand stories put the protagonist to a hard choice about a character-defining question surely require more. There are stakes—the protagonist chooses to risk his job, such as it is, to break rules to ensure his target comes to a gruesome end, and he accepts the risk his employers learn something that can be used against humans later. And there’s a lighthearted side: his daughter’s imagined responses to the teen mag survey give her a perfect score: Yay! It’s dark, but revenge is best that way.

Ruston Lovewell’s dark fantasy “Release from Service” follows an apprentice to a government-sanctioned assassin as his master sets him on quarry close to his heart. The protagonist’s ambitions and identity are entangled with the need to comply with his instructions, and flashbacks depict his history earnestly performing as instructed. If you enjoy revolution against establishment oppression, you will enjoy the fuel Lovewell employs for the climax. The final conflict sequence includes reveals, reversals, and surprises; the resolution happily addresses not only the immediate problem in the scene but resolves ongoing interpersonal plot threads that run from the story’s open. Lovewell’s hopeful conclusion brightens a world the narrator’s jaded earlier self had resigned to accepting with all the darkness he found in it. If you enjoy stories that strum your feelings about family, love, loyalty, reconciliation, and hope, “Release from Service” could be for you.

David Cleden’s “Dark Equations of the Heart” is a fantasy that replaces society’s outlook on vices like sex and drugs with its fictitious society’s outlook on mathematics. For example, a house of ill repute contains a man whispering about theorems to clients for coins, only to be forced by a pimp who threatens the woman he loves until he agrees to take a gig he fears is too dangerous. Public speakers advocate freedom to enjoy the ecstasy of mathematical theorems. The entertaining concept doesn’t by itself create interest in the protagonist’s goals, or understanding what they may be besides avoiding the consequences threatened by more powerful men. And while that’s frustrating at first, it turns out to be the root problem at the core of Cleden’s tragic resolution: when threatened, the protagonist succumbs. He is unwilling to risk himself to resist oppressions any time he’s issued a threat, and by folding to pressure soon risks delivering to the villain a dark mathematical concept which the villain must kill the protagonist’s love interest to read in the scars left by her surgeon on her heart. By the time he’s apologizing, it’s too late to save his relationship with the woman he should never have been so cowardly as to be driven to betray. The circumstances neatly place the protagonist and his dreams in jeopardy, the problem is nasty to envision, and it all feels well-matched to the grim world in which it’s set.

Christopher Baker’s “An Itch” is a first-person fantasy about an enchanter’s enchantress daughter who grows up distant from, though within sight of, her mother and nonmagical sister. What goes wrong for the narrator—and fuels the reader’s desire to see change—seems to flow entirely from the off-screen activities of others rather than the narrator’s own goal-directed effort. The protagonist’s intra-family tensions generate a sense of conflict, but the narrator doesn’t seek to oppose anyone: they don’t produce a concrete objective for the protagonist to achieve, and it’s hard to tell (except when she’s enjoying something magical) whether she’s succeeding or failing when she does choose to act. Since the problems and their resolution all seem to be powered by off-screen activity, the energy in the scenes that trigger emotion comes not from a character succeeding in some plan to advance a plot arc but the reader’s relief when something goes right for the narrator: a plant thrives, a magical working succeeds, a seemingly lost relative appears with a message of reconciliation. The characters’ interior—even the narrator’s—isn’t explained to readers; all the emotional content in their actions is supplied by the reader, so the interactions all feel as real as the reader feels can be evoked by the relationships. Interestingly, nobody claims to change in order to explain any of the reconciliations: the characters just seem to mature and realize they should get along. Since decades pass during the story, this feels plausible. Baker conjures a feeling of resolution without showing anything actually resolved: magic. Beautiful passages combine with a sympathetic innocent protagonist to create a feeling of wonder.

Details like the yellow light in the protagonist’s trailer and the annoying buzz of cicadas combine with the protagonist’s dismissal by a judgmental mother to make Carrie Callahan’s “Dirt Road Magic” an urban fantasy infused with dystopic grit. Narrated by a teen struggling to work spells in his trailer without being noticed by a mother who wants her child out for the afternoon so she can entertain a boyfriend, “Dirt Road Magic” shows a protagonist not only personally powerless but seemingly dismissed by a parent who should be helping to build him up. The narrator’s intended mentor proves to be a hedge-wizard peddling magical intervention for cash. But it’s a low-magic world and trailer-park cash. Dismal. The last scene returns the narrator to the trailer and his mother, and allows a re-evaluation in light of his experience shadowing the hedge-wizard’s work peddling the magic equivalent of heroin. The narrator’s climactic choice suggests a theme of self-reliance, while putting a sympathetic gloss on his mother. It would go too far to say the conclusion shows things are looking up—the trailer-park dystopia doesn’t support rosy optimism—but it appears the narrator is thinking for himself, and that’s always a strong place to put a maturing protagonist.

Preston Dennett’s SF “A Certain Slant of Light” builds interpersonal conflict on a classic SF question: is the protagonist’s theory ahead of its time, or a dangerous delusion? The protagonist walks every day to view the image of his wife, frozen at the edge of a time bubble that seems to have the capacity to trap forever anyone who enters its border. Is the prevailing theory correct, and the images reflect a world long dead on the other side? Or did the protagonist notice his wife move, subtly over the years, just a little—proving she remains alive within? In a tradition that dates at least as far back as The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, the protagonist uses himself to test his theory. The emotional power comes from the reactions of his family to his faithfulness to his wife’s memory, and then to his conviction she remains alive. Once the protagonist becomes convinced of his theory, it’s not a hard choice what he must do: the climax isn’t about the choice so much as readers’ emotional response to his relationship with his various loved ones after he decides to risk his life on the conviction he still has a wife to visit.

C. D. Lewis lives and writes in Faerie.

♣ ♣ ♣

[Editor’s note: Galaxy Press President John Goodwin has written an article detailing some of the many accomplishments of the Writers of the Future Contest winners over the past 35 years here.]