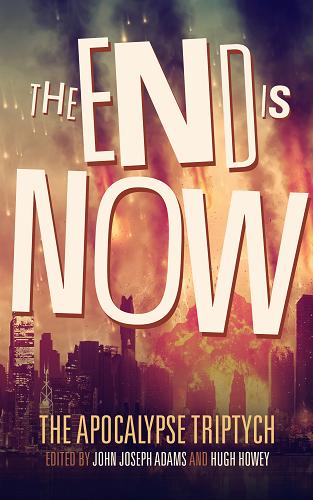

The Apocalypse Triptych Book 2

Edited by John Joseph Adams

(September 2014)

Reviewed by Charles Payseur

The end of the world has been a source of fascination for writers since the earliest narratives. Here, The End is Now continues the tradition by providing a glimpse into twenty possible ends of the world, some definitely more realistic than others but all of them circling around the idea of world destruction. This is the second volume in the Apocalypse Triptych, and most of the stories included in the anthology (seventeen of them) are the second parts of triptych tales. As such, some of the stories will make a bit less sense to readers who did not read The End is Nigh, though they can, more or less, be read independently. What this anthology focuses on is the immediacy of the end, of apocalypses happening, of survivors, or almost-survivors. And because of that, The End is Now is equal parts despair and hope, ending and beginning. The old worlds are crashing down, and something new is taking shape, though what that is remains obscured, waiting to be revealed in The End has Come, the last of the triptych anthologies that will release in March 2015.

A woman named Nayima finds a fellow survivor and a little hope in Tananarive Due‘s medical apocalyptic story “Herd Immunity.” After the population has been nearly wiped out by a deadly plague, Nayima finds herself one of the few NIs, or naturally immune. Wandering the country, she finds something of a purpose when her path crosses another man’s, and she follows him to a nearly abandoned town. There she is disappointed to find that he is masked, that he doesn’t believe that he is immune, and that he wants nothing to do with her. Nayima explores the town, finds vital supplies, but refuses to move on, wanting instead the human connection that the man offers. When she starts to draw him out of his shell, though, she learns a hard lesson, and in the end finds herself a little wiser but no less alone. A haunting story, Nayima’s journey is marked with small moments of hope and larger moments of despair as she navigates the sundered country. And there was little defense indeed from the gut-punch of an ending that left me silent for a long time from its impact.

“The Sixth Day of Deer Camp,” an alien invasion tale by Scott Sigler, follows George and his small band of friends as they contend with both the cold and an alien craft crashing near their hunting cabin. Trapped inside by sub-freezing temperatures, they decide they need to act, and trundle out into the snow in time to avoid being blown up with it as an alien in a robotic suit arrives and attacks. Luckily for them, the suit is damaged and a volley from their hunting rifles takes the creature down. Without shelter in the bitter cold, the group decides to head back to the alien ship, and finds something they hadn’t expected: survivors in the form of alien children. And as the men face the implications of that discovery, George considers what kind of welcome the aliens will receive on Earth. Leaning on an interesting friend dynamic, the story was entertaining enough, but I felt the ending could have blazed a fresher trail than it did.

Annie Bellet chronicles the travels of a woman named Lucy and her boyfriend as they flee through an America being bombarded by meteor strikes in the near future with “Goodnight Stars.” After learning that meteors have destroyed the moon and are raining down on Earth during a camping trip in California, Lucy fears for her mother, a scientist stationed on the moon, and decides to try and get to Montana where her father lives and might have news. Together with her boyfriend, Jack, and friend, Heidi, Lucy drives across a panicked countryside, protecting herself from deer, near-misses, and lawless bullies. The group nears Lucy’s father’s home only to get caught too close to a fall, and Jack and Heidi are injured, Heidi mortally so. Finally making it home, Lucy hopes to put her life back together, and receives the truth about what happens to her mother. Stark and sweet, the story moves nicely, and the relationships between Lucy and the other characters are solid. The ending, though, was a little too much whimper for me and not quite enough bang.

Rock Manning begins to question life as an internet movie star as the world goes crazy around him in the bizarro-flavored “Rock Manning Can’t Hear You” by Charlie Jane Anders. Rock, a bit of a loser who can’t stay still since the violent death of his friend a short while ago, finds his life a strange mockery of reason as he acts in internet movies as random as they are popular. With growing gusto he and his friends produce films heavy on violence and slapstick that the public laps up, hungry for some distraction for the war and policies that are tearing the world apart. After a co-star is killed, Rock decides he has to stop, but before he can an attack of some sort renders everyone on Earth deaf, and his movies become even more important. Hounded by the crushing realities of life, Rock has to decide what he is going to do, but doesn’t quite settle on anything. Interestingly told with a reliance on its short attention span and crazy images and ideas, the story didn’t quite stand on its own. Perhaps when read with its first part and third it would provide a satisfying whole, but alone it was entertaining but left me wanting more.

A mother fights to keep her and her daughter safe from a mold she had a hand in creating in “Fruiting Bodies,” a biological apocalyptic tale by Seanan McGuire. Having been a part of the team that had inadvertently spawned a mold that feeds on living organic matter, the woman had to watch as her wife was its first victim. But not its last. Still holding on thanks to her own OCD cleanliness, she tries to keep her daughter safe, only for an act of teen rebellion to undo all her careful work. Her task shifts from keeping her daughter safe to trying to hope she can keep her as long as possible, but even though the woman passed on some of her natural resistance to her daughter, it is not enough, and eventually she has to confront that she will soon be alone, though not for very long if she has any choice in the matter. Full of guilt and obsession, the story does well focusing on the dynamic of mother and daughter in a world where OCD is the only way to survive. Perhaps a little overly sentimental at times, the story still managed to be emotionally resonant and engaging throughout.

It turns out the end of the world is the least of Nicole’s problems in the science fiction horror story “Black Monday” by Sarah Langan. Waiting for the impact of two asteroids, a team of scientists works to try and create a construct that will be able to survive on the surface following the destruction—a human brain in a mechanical body. Complications arise, though, when the military leader they are working with snaps and blows up the shelter that their area was supposed to live in. Making due with what they have, they cut corners until they have something they suspect might work. Of course, it requires a volunteer to be the brain, and after some debate one of them steps forward. At first the experiment seems to be a failure, but as the asteroids impact it turns out that failure might have been a better option. Full of good intentions and terrible results, the story was tense and compelling, and shows some of the dangers of rushing things in the face of extreme situations.

“Angels of the Apocalypse,” by Nancy Kress, reveals the plight of a world falling into chaos as generation after generation is born Sweet, unable to commit violent actions, even to the planet. Sophie, one of the last regular people, has to live with constantly having to protect her sister, Carrie, who is a Sweet. As the world sinks, though, anger and conspiracy theories begin to blame the Sweets for the problems, begin to target them as an outlet for all the anger and resentment felt by people who can never live up to that example. Though scientists continue to look into what caused the genetic mutation, the rest of the population doesn’t have the patience to wait, and while Sophie battles her own demons when dealing with her sister and the Sweets, she also knows she can’t just let them be destroyed. Full of a quieter sort of apocalypse than many in the collection, the story still sets the stakes high, and while things were a little crowded when an alien craft gets added in, it was never confusing and had me enjoying the action throughout.

New York is the site of a massive zombie outbreak through which a group of survivors try to escape in David Wellington‘s science fiction horror vision “Agent Isolated.” Formerly the CDC agent in charge of containing the outbreak in New York, when Whitman was marked as being potentially infected he defected and tried to escape the quarantine that he helped set up. Having picked up a group of other potentials, Whitman drives through a city overrun with zombies and threatened by fire, all the while aware that being marked makes him less than a citizen, makes him a threat to be wiped out. He and his fellow potentials follow a hope of escape, but upon reaching it discover, to their horror, that they escaped zombies only to be betrayed by their own government. Of course, Whitman manages to save himself, but only to get back to creating the programs that doomed the people with whom he had been traveling. Bitingly told, the story moves well enough, but the nature of the zombies never made sense to me, and in the end I couldn’t feel bad for Whitman, which made the final sequence more frustrating than anything.

Ken Liu sets the stage for a global war in his techno science fiction tale “The Gods Will Not be Slain,” though it’s not where anyone thinks to look for it. After a group of humans have their minds uploaded into the internet, they begin a shadow war, some trying to use the computers of the world to bring about utter destruction while others strive to save it. Maddie, a young girl whose father is one of the computer-people trying to save the world, must watch as her father falls victim to his enemy and the world descends into war. She holds to the hope of reviving her dad at the place where he was uploaded, and succeeds, though in doing so opens the world up to greater threat. Her father, in his last act, takes Maddie’s advice and tries a dangerous gambit, one that neutralizes the threat and creates something no one anticipated. Interesting as an idea, I felt the story relied a bit too much on summary and unseen action to really engage me. Like some of the other stories so far, as a middle part it might be okay, but as an independent story it felt a little weak.

The Fever has decimated the Americas and Alyce walks from Colorado to San Diego to return to her family in “You’ve Never Seen Everything,” near future science fiction by Elizabeth Bear. Having been stranded when the Fever swept through the nation, turning everything into a shell of what it was, Alyce makes her way west, bartering when she can, stealing when she has to. After crossing the Rocky Mountains, she comes down with the Fever herself and barely manages to survive. With time and resourcefulness, though, she makes her way back to San Diego, back to her partner and daughter, only to find things a little more complicated than she thought they would be. Vivid and movingly told, the story does a great job of revealing the world ravaged by the Fever, and what kind of thinking is required in that kind of world.

In the off-world science fiction story “Bring Them Down,” Ben H. Winters sets up two survivors of a human colony, alive because one couldn’t hear the word of God telling everyone to kill themselves, and the other heard but disobeyed. Pea, the girl deaf to the voice that caused all the other colonists to kill themselves, finds herself unable to be sad. She thinks simply of what needs to be done, of what she and Robert, the boy hounded by God to kill her, have to do. And what she decides is that they have to dispose of all the bodies of the dead, carting them out to the outskirts where they won’t attract animals. Only Robert can’t resist the power speaking into his head forever, and when he succumbs Pea finds that her deafness wasn’t permanent. Well balanced between the two protagonists, I enjoyed the story at the same time I felt that not enough was revealed to make complete sense out of it. The setting was interesting, but without an idea of what was really going on I was left wanting more from the ending, chilling though it was.

As the world is washed in unrelenting acid rain, a few survivors party at the end of the world in Chicago, and a woman who may have caused the trouble learns that things might go on in Megan Arkenberg‘s “Twilight of the Music Machines.” Friday, a girl who lost her mother to the shortages caused by the rains, lives in a series of parties with her kind-of boyfriend Cloud. Together they try to celebrate while the world is eaten around them. And Vanessa, a woman who Friday brings water to, seems to be more than she lets on as a woman from out west begins painting strange pictures around the city in hopes of finding her. Put off a bit at Vanessa’s gruffness, Friday remains curious, and when she confronts the woman she finds a resolve and strength in herself she didn’t know she had, a courage in the face of the rains. Revealing just enough of the calamity to make everything make sense, the story lingers on the small moments these survivors share, the parties at the end of the world, the small victories in the face of death.

Tom, a young man on the verge of graduating from the police academy, finds his future a little bleaker when his mother gives him the directive to protect his young brother in Jonathan Maberry’s zombie horror story “Sunset Hollow.” Unsure of what is happening, Tom watches in terror as his mother pushes him out into the night and turns to face what was once her husband. Shock very quickly becomes a fight for survival, though, as Tom braves the hordes of zombies and tries to find a safe place. Unfortunately, safe places are few and far between, and between the zombies and a nuke-destroyed Los Angeles, Tom finds his options rather limited. His one goal becomes keeping his brother safe, though it weighs on him heavily. Short and to the point, the story doesn’t bother with hows or whys, instead focusing on the confusion and impact on a pair of brothers as they face the end of the world together. And for that it’s satisfying and visceral, with blood and tears and sense that the trouble is only just getting started.

Jake Kerr tells the story of Sam, a man escaping a North America doomed by an impending asteroid strike, in “Penance.” Having been a government employee, Sam had been exempt from the lottery to see who would be allowed to leave the continent. But his job with the government had been to inform people that they had not been selected by the lottery, a job that left him damaged from the hope he had to destroy, to the people he had to tell were being left to die. As he travels by boat across the ocean, Sam cannot face the other passengers, sees in them the reflections of people he had to condemn. After the asteroid hits, though, and the ship is in danger of sinking, Sam finds something that helps, something he never had the chance to do in his job. He saves someone. Well crafted between scenes of the present and flashbacks to his job, Sam’s torment and guilt are well built and effectively shown. And while part of the ending seemed a little too convenient, it still made for a good message and entertaining story.

The end of the world is more a metaphorical thing for a pair of mechanical avtomats once Peter the Great of Russia dies in the historical fantasy “Avtomat” by Daniel H. Wilson. Their sole benefactor, Peter the Great, created the pair, named Peter and Elena, to rule Russia forever, but his wife Catherine has other plans, viewing them as inhuman abominations. They flee her violent wrath, but pursuit catches up to them, and only thanks to their mechanical nature are they able to survive, though Peter is greatly damaged. Carefully Peter is able to free them, and together they escape to try and find others like themselves, other avtomats that might understand their plight. A bit of a departure from the rest of the stories in the collection, this one is interesting for its differences, and does represent a world ending, just not a physical one. As an apocalyptic story it might not quite succeed, but as an historical fantasy it worked well enough.

A virus that freezes people in place so that they die of dehydration is the backdrop for a more intimate story of a marriage facing its end in Will McIntosh‘s contemporary tale “Dancing with Batgirl in the Land of Nod.” Eileen picks the end of the world as the time to reveal that she’s been unfaithful to her husband Ray, who doesn’t know how to take the news. Shattered, he retreats back into his private fantasy, his happy place, in this case into the old Batgirl television show. Shrinking away from his wife, he seeks out Helen Anderson, the actor who portrayed Batgirl, and the two form a quick bond. Still guilty about leaving his wife, though, Ray brings Helen back to his house, and there they all succumb to the disease. Immobile but still aware, Ray is forced to think about how he faced the end, the mistakes he made, and as an immune friend poses him with Helen instead of his wife, Ray wonders if he shouldn’t have done things differently. Melancholic and shocking at times, the story works well with the relationships between the characters, bringing them all artfully to the last scene, dancing as the world ends.

The poisoning destruction left by a passing comet wipes out social classes, or perhaps flips them, in “By the Hair of the Moon,” an historical steam fantasy by Jamie Ford. Dorothy, a Chinese girl sold into slavery in Seattle, escapes the devastation thanks to a kind of opium she had been taking, something that made her immune to the poison brought by the comet. Most were not so lucky, though, and the city suddenly finds itself without the crushing class system that held the poor down for so long. Dorothy flees one mob only to run into another, a hunting party of wealthy men who see her as game. Fate has spared her for a reason, though, and Dorothy resolves to live, to fight, to find her destiny in the new world the comet has brought. Quick and sharp, the story is full of grit and grime and human suffering, but with a small hope as well, a hope that sometimes it takes destruction to clear the way for fortune.

“To Wrestle Not Against Flesh and Blood,” by Desirina Boskovich, follows Annette, the oldest child in a large rural family, as her father prepares to attack a government already dealing with an alien threat. When the aliens arrived it was to promise a better world, though Annette’s father was certain it was a fake, a conspiracy from the government to take their rights. When the salvation turns out to indeed be fake, her father is that much more convinced, and angry because his wife was killed due to alien “mandates.” He organizes a militia out of their home and prepares to attack, and Annette simply tries to survive, to keep her siblings safe. After she sees a craft in the sky, however, she tries to warn her father, who ignores her protests, and he pushes ahead with his plan anyway. Alone with just her younger siblings, Annette is left to pick up the pieces, to survive in the face of everything, not particularly caring about conspiracies or aliens or gods. The story captures the feel of a home-brewed rebellion, and how moderate voices can get drowned out in the sea of crazy that conflict can bring. And Annette is a compelling character, complex and practical, who makes the story worth reading.

Hugh Howey crafts a story of a group of people forced to make a hard decision, and then forced to make an even harder one with “In the Mountain.” Tracy is one of the Founders, a group of people responsible for creating a refuge of sorts deep underground. They are escaping the machinations of the government, which is aware of a fatal flaw in a program that, if exploited, could kill everyone on the planet. Instead of letting some enemy trip it, though, the government decides to kill everyone itself so that it will be prepared for the consequences. Tracy and her group found out, and brought their family and friends down below for what they thought would be six months. When the real time table turns out to be five hundred years, though, they make the decision that instead of living together for a year, fifteen people will live on, will procreate to only replace the dead, to make sure that those responsible for ending the world pay for their crimes. And Tracy makes a decision about who to save that she hopes will make a difference, if only to herself. Tense and original, the story shows the conflict and fear in this group of people, and the kind of thinking that can lead to mass murder as the best option available.

A woman writes a series of letters to the men that left her in the apocalyptic “Dear John” by Robin Wasserman. The letters pull no punches and reveal a life of toxic relationships with men who didn’t care for her, who abused and insulted her. Desperate for love, for someone to stay with her, she thought she had finally found a good match only for him to develop cancer. Hopeless, she had taken refuge with a religious group who prophesied that the world was going to end, and it did. An asteroid strike and a nuclear war later and the group is safe in their compound, though it is run by a twelve-year-old boy who doesn’t seem the most collected. And as the woman thinks back on all the people in her life, all dead now, she wonders if she is stuck in the same pattern or if, perhaps, there is still hope, and so writes one last note to the man she’s about to leave. The story hits hard, and is powerful and sharp. It draws very heavily on standard male tropes, calling out not by name but by type. For all the anger and hurt, though, I found the caricatures a little limiting, a little too bound to very familiar roles, and would liked to have seen something a little more diverse than those presented.

Charles Payseur lives with his partner and their growing herd of pets in the icy reaches of Wisconsin, where companionship, books, and craft beer get him through the long winters. His fiction has appeared at Perihelion Science Fiction, Every Day Fiction, and Dragon’s Roost Press.

The End is Now:

The End is Now: