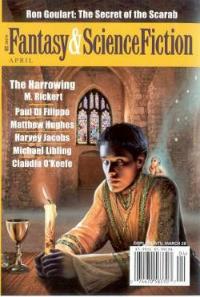

"The Secret Sutras of Sally Strumpet" by Paul Di Filippo

"Domovoi" by M. K. Hobson

"The Secret of the Scarab" by Ron Goulart

"Black Deer" by Claudia O'Keefe

"A Friendly Little Oasis" by Harvey Jacobs

"The Gospel of Nate" by Michael Libling

"Finding Sajessarian" by Matthew Hughes

"The Harrowing" by M. Rickert

It can be difficult to find good humor in science fiction and fantasy. We seem, by nature, to be a rather po-faced and earnest genre. Connie Willis, Terry Pratchett, Robert Rankin, and Esther Friesner are, to lesser or greater extents, masters of genre comedy, while authors like Bradley Denton or Jack Womack offer a more laconic edge. Another name that must surely spring to mind when listing our more prominent humorists is that of Paul De Filippo whose Plumage from Pegasus column has long been in turns a witty and a confusing feature of F&SF, and whose novelette "The Secret Sutras of Sally Strumpet" opens the April issue of F&SF.

It can be difficult to find good humor in science fiction and fantasy. We seem, by nature, to be a rather po-faced and earnest genre. Connie Willis, Terry Pratchett, Robert Rankin, and Esther Friesner are, to lesser or greater extents, masters of genre comedy, while authors like Bradley Denton or Jack Womack offer a more laconic edge. Another name that must surely spring to mind when listing our more prominent humorists is that of Paul De Filippo whose Plumage from Pegasus column has long been in turns a witty and a confusing feature of F&SF, and whose novelette "The Secret Sutras of Sally Strumpet" opens the April issue of F&SF.

Frustrated at his lack of literary success, writer Riley Small has decided to write an über-chick lit novel, The Secret Sutras of Sally Strumpet, under the Nom de Plum of Sally Strumpet. His book has been far more successful than even he had hoped, and with a movie deal about to be finalized, the author must step into the spotlight. Knowing that the author of The Secret Sutras can't possibly be revealed to be a man, Small and his abrasive agent, Harvard Morgaine, begin to interview stand-ins. But none of them seem right, until Small's own creation, Sally Strumpet, walks in the door, and Riley Small finds her taking over his life and success.

De Filippo's story is both lively and funny. The humor arises nicely from the story itself, rather than being tacked on. His satirization of some of the clichés of chick lit, through the secret sutras (Number 3: "Intense private conversation between a man and a woman is the high road to a lowdown activity," for example), is as spot on as his take-offs of science fiction and fantasy have been. The agent, Morgaine, is obnoxiously delightful and a amalgam of the best and the worst traits of many agents. De Filippo's prose is sharp with wit ("Halfway through a rerun of Who Wants to Create a Reality Show?, there came a rather assertive knocking"). And the end of the story is as natural as it is clever.

F&SF provides more humor than most other spec fic magazines. It tends to be of fairly variable quality. This one, however, is a hit. "The Secret Sutras of Sally Strumpet" is a delightful, light start to the issue.

M. K. Hobson's "Domovoi" boasts one of the most wonderful opening lines I've read for a long time:

"You're a murderer and a rapist, and there may be no hope for you," Winnie says to Ryan on a rainy afternoon at the end of the story. "But if there is, I will find it. I will remake you."

It is a brave tactic to start a story by telling the reader exactly what is going to happen at the end, but Hobson has both the courage and the talent to pull it off.

Ryan Ceres is a real-estate developer, whose single passion–his love–is renovating derelict buildings and turning them into pristine, gleaming shops, offices, and apartments. The long-abandoned Windsor Machine Works seems like just the project for Ryan, or it would be if it were in a better part of town, but he feels compelled to take it on nonetheless. All seems well, until he comes across the ugly, misshapen, drunken squatter, Winnie, in one the rooms. Because she is not simply a squatter, she is the Domovoi, the spirit of the building, and she doesn't want to change.

Hobson's story cleverly plays off the contrasts between Ryan's fiancée, who is as pristine and gleaming as the buildings that Ryan has renovated, and towards whom Ryan feels absolutely nothing, and the transformation that he brings about both to the Windsor Machine Works and Winnie. At its heart, this is a story of redemption, not of Winnie or the building, but of Ryan himself.

M. K. Hobson is a fabulous writer; her prose is beautiful and focused, and she gracefully brings alive her subjects. This is a story to read again and again, not just to appreciate the subtleties of the story, but simply to delight in Hobson's craft. This is undoubtedly the strongest story in this month's F&SF.

Ron Goulart is a writer of impressive pedigree. He has published stories in most of the major genre magazines and dozens of novels. He has also written several works of non-fiction. Sadly, you would realize little of this from reading "The Secret of the Scarab," a by-numbers historical-fantasy detective piece.

Harry Challenger is a late-nineteenth century private investigator whose specialty is investigating the supernatural. While in London, he is employed to look into the murders of several Egyptologists. The clues are provided by the conveniently-timed visions of a magician friend and answers by the beautiful young wife of his client. Magic offers a writer both problems and opportunities. Done well, the limitations and the price of magic can vastly strengthen a story. Unfortunately, Goulart appears to have chosen to simply use the magic here as an easy way around obstacles and thus there is little in the way of challenge for Challenger.

The setting of "The Secret of the Scarab" is fantasy-tinged, and there is some fun to be had in picking out the references that Goulart has inserted into the story. Goulart also evokes the familiar atmosphere of late-nineteenth century London nicely and loads the story with humor, although much of that falls flat. What really lets this story down, however, is that there really is nothing new here at all. The characters and plot are all straight off the templates with no effort expended to flesh them out, and Goulart's writing is awkward, even clunky in places. The story trails away to an unconvincing ending. If you are not reading for these things, then Goulart's story is fast paced and stuffed with action, and that may be enough to satisfy. Goulart might have made something more of this story, but "The Secret of the Scarab" lacks either Hobson's mastery of prose or De Filippo's sharp wit, and so ends up insubstantial.

Memory and reality are the twin themes of Claudia O'Keefe's subtle "Black Deer." The story takes us on a journey through the back roads of Virginia in search of memories. Once, twenty years ago, Caroline saw a herd of black deer cross a road in front of her, deer that just couldn't have existed. Now, spurred on by the realization that another of her memories from long ago was of something that never actually happened, she and her ex-husband, Sandy, have taken off on a road trip, leaving behind Caroline's new fiancé, so that Caroline can find out whether or not this memory is false too.

For most of its length, this is a fairly ordinary story, although well enough put together and smooth in its interweaving of past and present. Only at the end does it step beyond the ordinary to the extraordinary and re-illuminate all that has happened before in that less ordinary light.

It is tough to hang a whole story on the ending. It asks the reader for a lot of trust. But O'Keefe manages it here and rewards the reader for their trust. Where M. K. Hobson offered us a lesson in constructing perhaps the perfect opening, O'Keefe does the same here with the perfect ending.

"Black Deer" is a story that asks us to consider memory and reality and to reflect on the loss of things that may never have been. As such, it is one of this issue's more thoughtful pieces and it offers much-needed variety from the humor and lightness that dominates many of the other stories.

Harvey Jacobs provides another of this month's comic pieces in "A Friendly Little Oasis." Kovacho is a vampire. Things have become too hot for him in Manhattan so he's moved into a small town where he can have some rest and peace, and where everything moves more slowly. The people here, too, are much more enticing prey than he is used to. They are fat, succulent, and ripe to be eaten. And no interfering government regulations have done away with the waste incinerators he uses to do away with his victims' bodies. However, not all goes to plan. The moving van with his possessions in is held up by bad weather leaving him with only the clothes he is wearing, and when he feeds, he manages to spill a drop of blood on his collar. When he takes his evening walk, he is constantly stopped by passers-by who want to give him advice on how to remove the stain. Each one of them, as an aside, mentions vampires. By the end of his walk, Kovacho has gone from being polite to enraged.

The story is a simple comic take on moving from the anonymity of a big city to a town in which everyone feels your business is their own, with the added twist of the protagonist–a vampire–really having something to hide. The problem it suffers from is that it is essentially a one-joke story, and that joke is repeated throughout. A repeated joke can grow funnier, done right, but it doesn't here. There is nothing intrinsically bad about "A Friendly Little Oasis." It's just that there is little of substance here, and the story is quickly forgettable. Still, it is short enough and will bring a smile.

Fantasy tends to dominate science fiction in most issues of F&SF, and the same is true in this issue. Along with Matthew Hughes' short story, Michael Libling's "The Gospel of Nate," is the only science fiction for April, although its premise intersects somewhat with fantasy.

The setting is fairly near-future. Technology now allows people to regress–to access the lives they lived in previous incarnations. Nathan Stark works in a down-market salon, running the night shift, dealing with the lunatics and the unstable and their claims to have been various famous people in the past. Stark himself, despite taking hundreds of "dives" into the past, has always drawn a blank on past lives. Hoping to impress a waitress he has fallen for in his local café, he offers her a free dive for her birthday and all is looking good for Nate, until she returns and claims to be the reincarnation of Jesus, Buddha, Moses and just about every other significant religious figure from history. So far, so good.

Things only get worse for Nate when, after her next dive, she tells him that she is also the reincarnation of as many fictional figures. Unfortunately, this is where an otherwise promising story gets a bit, well, silly and jumps the rails. The explanation the story offers stretches credibility too far. Which is a shame, because it started stylishly and with some verve. There's plenty of good stuff in the story–Nate and Sam, the waitress, are great characters, and there is plenty of texture in the believable setting–and Libling pulls it together well at the end. But the story would have been better served if the sillier parts in the middle had been excised.

Matthew Hughes has been a frequent contributor to F&SF, sharing, among others, his stories of Henghis Hapthorn, the world's foremost discriminator, and his increasingly sentient and independent integrator. "Finding Sajessarian" is the fourth of these stories (following "Mastermindless," March 2004, "Relics of the Thim," August 2004, and "Falberoth's Ruin," September 2004). The stories share a common format, mixing Hapthorn's private investigations with the obscure games and puzzles set to him by a being from another universe.

In "Finding Sajessarian," Hapthorn is approached by the notorious blackmailer and extortionist Sigbart Sajessarian who wants Hapthorn to try to track him down, as a test of how well he can hide from the potential victims of a scheme he is about to execute. But this is mystery story as well as a science fiction piece, and things are not as they seem.

At the same time as this mystery, Hapthorn is engaged in a new and distracting game with his other-dimensional opponent, and his integrator is growing increasingly truculent.

Hughes' Hapthorn tales are set on a far-future "Old Earth," a setting that allows the author considerable freedom to display his fine, inventive imagination. As such, this is only science fiction in the broadest sense, sharing much in conception with fantasy and following in the tradition of works by Vance, Wolfe, and Zelazny, although Hughes' stories are lighter and more whimsical.

I thought that in Hughes' last Hapthorn story (F&SF, September 2004), the elements of the story did not fully link together and that the mystery was rather perfunctorily solved, without the process of deduction being revealed. This time around, the story is far more neatly integrated. The mystery that Hapthorn solves, too, is given more weight, even though it is not the main focus of the story.

The Henghis Hapthorn tales are a part of an evolving universe of stories. With "Finding Sajessarian," Hughes has developed that universe further and has tantalizingly introduced a new element, the idea of the Great Wheel turning to the point where "rationality begins to recede and what you call magic reasserts its dominance". "Finding Sajessarian" is a light piece, but it is likable, funny, and effective. We are promised another Henghis Hapthorn story in the next issue of F&SF. I, for one, am looking forward to it. This is an increasingly interesting series.

The April issue of F&SF closes with M. Rickert's "The Harrowing," another redemption story, but in a distinctly different vein from Hobson's "Domovoi." Our protagonist is at the end of a self-indulgent trip across America, inspired by the likes of Herman Hesse and Allen Ginsberg, seeking to find himself. He is also at a personal turning point, having just mugged an old man for the cost of his trip home.

While sitting waiting for his train, a disturbing elderly man joins him and proceeds to tell a story from his own youth, when he enrolled in a seminary and, along with other trainees, fell under the influence of a strange, perverted priest, Father George. Father George initiates the six young men into mystical secrets and rituals and tells them of the Harrowing, when, supposedly, the crucified Jesus descended into Hell and released the evil souls there to walk on Earth again before his resurrection. Father George had another aim in mind for at least one of those young men, however. The disturbing old man has a message for our protagonist, too: he will never attain his dream of being a writer, no more than the old man was able to become a priest after his experience.

Redemption comes in a variety of forms, and this redemption is a subtle one for Rickert's protagonist, but despite the differences, as in Hobson's story, redemption comes through personal choice, a thoroughly contemporary premise. Rickert's story is well written and reasonably interesting, however it doesn't particularly stand out. Despite its original elements, this is a fairly well-worn type of story. Rickert handles it as well as most, but it doesn't surprise. A good story, just not exceptional.

Summary

There are six fantasy stories in this issue, and two science fiction stories. Two of the stories ("The Secret of the Scarab" and "Finding Sajessarian") are also mysteries. Four of the stories are humor and four are straight. The weakest stories perhaps come when the humor does not work as it should.

There is almost always one outstanding story in an issue of F&SF. In this issue, that story is M. K. Hobson's fantastic "Domovoi." Paul De Filippo's "The Secret Sutras of Sally Strumpet," Claudia O'Keefe's "Black Deer," and Matthew Hughes' "Finding Sajessarian" are also very good. This was a fairly average issue of F&SF, showing the good mix of story types and styles that we are used to from this magazine.