Asimov’s, March 2015

Asimov’s, March 2015

Reviewed by Charles Payseur

It’s a murder mystery on the Moon featuring clones and some legal murky water in “Inhuman Garbage” by Kristine Kathryn Rusch. When Detective DeRicci begins investigating a dead body dumped into a compost recycling bin, she starts unraveling a strange case that walks some very unpolitical lines. Unpolitical both because the case draws close to Luc Deshin, a business man with a criminal reputation, and because the victims are clones, not even considered human under Earth Alliance law. DeRicci, wanting to see justice done, pushes forward regardless, but her investigation is doomed to failure, the victim of the system at work on the Moon. That doesn’t mean that things don’t get done. Deshin, while a legitimate businessman, is also fiercely protective of his family, and as the case opens his eyes to a breach in his security, he takes it on himself to act quickly to make sure such an incident never happens again. What follows is something of a lesson in how things work in this city on the Moon, a weird dance that isn’t entirely satisfying but that brings about a sort of justice, even if it’s missing the official approval of the law. The story manages to weave an interesting mystery, and while it leaves a few characters sure that they’ve lost, it pulls off a fairly fitting ending.

Joseph, time agent of the Company, has his work cut out for him in stopping a string of art-related deaths in Justinian Constantinople in Kathleen Bartholomew and Kage Baker‘s “Pareidolia.” Like with most Company stories, the charm is in the way the past and future meet, Joseph being an immortal agent partly responsible for shaping the past to make sure that things run smoothly. When, in ancient Egypt, he created a formula to improve architectural knowledge so that the pyramids could be built to last thousands of years instead of falling over immediately, he thought he was just doing his job. When the same formula shows up in Constantinople, though, it turns out it has some effects when worked into art that Joseph did not foresee. Men start dying from looking at the works created using the formula, which is bad news for the Company, which always tries to keep a low profile. So Joseph is dispatched to retrieve the formula and the powerful art. It’s a fun story, though rather airy and without an awful lot of impact. For fans of the Company hungry for more after the passing of Kage Baker, this should come as welcome succor, but for someone new to the setting it’s more just a light story about time management. Still, the humor is effective and the idea fun, and though it doesn’t seem the deepest of stories, it’s a pleasant enough read.

Gregory Norman Bossert tells the story of the crew of a ship making a living breaking ice on Europa and playing a game to get to know two new crew members in “Twelve and Tag.” The story itself is a series of embedded tales as the crew first demonstrates how to play and then listens to the new crew members tell their stories. They must tell two stories, one false and one true, and the rest of the crew has to tell which is which. It’s a great concept, this way of bonding with the crew, this way of learning to trust each other through stories. The new crew members aren’t quite what they say they are, and through their stories a whole tangled web is revealed, one that makes it so that the crew can trust neither of them. Things escalate rather quickly, leaving the ritual of the game intact and valuable, as through the game the truth is revealed before it might have endangered them all. It’s a slow story until it isn’t, until the weight of everything suddenly ramps up and makes the action boil. And there’s a sense of things slowly coming together and then shattering all at once. It shows the values of stories, and how they can draw people together and how they can tear people apart.

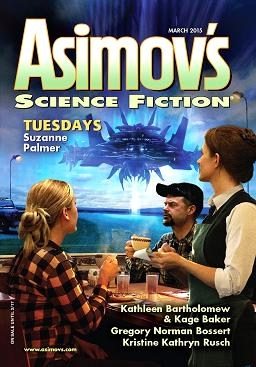

A quiet story about a pair of police officers gathering witness statements of a UFO sighting at a small diner, Suzanne Palmer‘s “Tuesdays” flits between a large and interesting cast as the officers try to figure out what happened. It’s not exactly a regular night for the officers, who find the diner populated with a motley bunch, a truck driver hauling illegal immigrants; a man on his way to visit a mother who recently suffered a fall; a woman regretting her life choices on her way to a reunion; a manager of an infamous music group; a waitress who knows a surprising amount about the UFO. It’s a great peek into each of the characters’ heads without bogging the story down with backstory. Each character feels real, feels alive as they give their accounts. And as the story winds to its end, despite the various secrets and dramas of the people at the diner, it’s the waitress who has the most tantalizing story of all. With a fun plot and great character work, this story is cute and understated and full of charm.

The loss of a father in war is approached with subtle care in “Military Secrets” by Kit Reed. Jessie gets the news of her father’s disappearance as a child, though her mother only tells her that her father is missing, not missing and presumed dead. And that simple difference, that hope that her father is still alive, that he will return at any moment, arrests Jessie in many ways. At school she is separated along with two other children whose fathers went missing, and together they board a bus that’s not quite right. People are crowded together, and no one ever seems to get on or off. Until the three start to talk about what happened. Until they realize that they’re on a bus with other children whose father’s went missing, and that the bus is a sort of purgatory or limbo, a place where they remain, unchanged, unable to really go forward because of the uncertainty and pain of their loss. They remain until they are able to move on, though when that might be is left a lingering question.

In “Holding the Ghosts” by Gwendolyn Clare, minds can be transferred into new bodies after death, made unaware that anything has happened thanks to memory alterations. But one body, that of a young catatonic girl, has hosted many personalities, and begins to gain a sort of gestalt consciousness, one that has wants and needs outside those of its ghosts. It’s an interesting story about identity, as the new person acts like the ghosts that inhabit it are driving the body at different times, and yet it wants to be more than just a sum of ghosts. Together they are something new and different and are committed to living. To doing something. The story moves smoothly, the ghosts all distinct and yet that question of identity lingering. Can something be unique that is cut from three different clothes? What kind of a life is it? Above and beyond all of these questions is the resolve that they can wait, that the most important thing is for this new life, this new consciousness, to find its own way in the world.

Charles Payseur lives with his partner and their growing herd of pets in the icy reaches of Wisconsin, where companionship, books, and craft beer get him through the long winters. His fiction has appeared or is forthcoming at Heroic Fantasy Quarterly, Fantasy Scroll Magazine, and Nightmare Magazine, among others. You can follow him on Twitter @ClowderofTwo