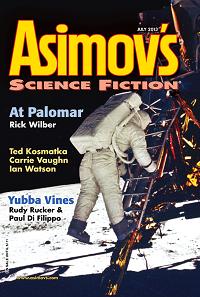

Asimov’s, July 2013

Asimov’s, July 2013

“At Palomar” by Rick Wilber

“Blair’s War” by Ian Watson

“Haplotype” by Ted Kosmatka

“The Art of Homecoming” by Carrie Vaughn

“Today’s Friends” by David J. Schwartz

“What is a Warrior Without His Wounds?” by Gray Rinehart

“Yubba Vines” by Rudy Rucker and Paul Di Filippo

Reviewed by Richard E.D. Jones

Asimov’s Science Fiction lives up to its name. This is some of the best science fiction around and, really, that’s just fact.

“At Palomar” by Rick Wilber takes a look at someone who, in our reality, offered a bit more than a footnote to most baseball fans. For Wilbur, though, the actually astonishing Moe Berg offered much more than a fantastic backstory. The “real” Moe Berg was an average – at best – major-league catcher.

Athletically, he was not all that big a deal compared to the rest of the players in the bigs. However, it was in every single other aspect of his life that Berg started to shine. A graduate of Princeton, Berg spoke more than 10 languages, won quiz shows and was a spy for the US Office of Strategic Services during World War II. To Wilbur, that just wasn’t enough.

The author takes us on a tour of a few different alterna-Bergs, possibly having something to do with an observatory being constructed at Palomar, located in our reality in California. But each one certainly having something to do with time travel, different timelines and, well, baseball.

Although a bit confusing at the beginning as we switch from timeline to timeline, the story is very well written and takes the time to show us how and why all these different realities matter and why Moe Berg is so important to them. The big question, though, is whether any of these are actual fiction or if the life story of our Moe Berg was only the tip of the metaphorical iceberg. No pun intended. Much.

World War II also figures heavily in another of the issue’s stories, “Blair’s War” by Ian Watson. This story deals with the aftermath of the German carpet bombing of the Spanish town of Guernica, and nearly four thousand children who rode an elderly cruise liner from Spain to Southampton in England.

Of course, it’s not what happened in our World War II, what with England having a Spanish king and all. Still, there is enough in common with our past to sufficiently ground the reader while the strange changes begin to kick in and really take readers on a very different journey into a very different past.

Watson, as always, does a very nice job with the prose. I’m not praising his ability to string words together to form a coherent sentence.He’s well beyond that. No, what I’m praising is the economy with which he builds his world, offering just enough to showcase the differences, allowing readers to intuit the ramifications of these differences.

Led by a General Blair, the British Expeditionary Forces have invaded Spain to repel the fascist forces of Francisco Franco and his Nazi allies. Blair’s War is not seen as a good thing in many places in England even though Blair, under a pseudonym, had been writing political propaganda for many years to seed the ground.

The conflict, such that it is, concerns a refugee named Josephina and her cousin, Esteban. He isn’t happy where he is, so he runs away to join Josephina. Eventually the two are reunited and, basically, that’s it.

The big twist of the story seems to come at the end with the reveal that Blair wrote his political columns under the pseudonym of George Orwell. Again, remember this was a well-told tale, but the tale wasn’t all that substantial. Interesting reveals at the end of the story don’t really, in my mind, make up for the lack of plot. Nice atmosphere, but the story itself doesn’t really go places.

In another world, in another story, the idea of going places is really all that matters. The world of “Haplotype” by Ted Kosmatka is a dark world, struggling through the aftermath of the Big Sick. It is a world of the TDR, a tuberculosis that is Totally Drug Resistant. Sadly, it is a world that is all too possible.

After the Big Sick, there are very few people left in the world. Unfortunately, one of those people is Doc, a big man with jaggedly broken teeth. He leads a paltry caravan of three other men and a young man named Nathan. They are traveling across the deserted dead lands between Native American reservations. For some unknown reason, the first people had the highest natural resistance to the TDR. They were the only ones who thought there might be a tomorrow, who actually planted crops as the world burned.

Doc, Nathan and the others are moving across those dead lands to find a reservation, searching for a place to call home, a place still alive. Doc, whatever he was like before the Big Sick, is a mean man without a cut-off switch to his anger. When he gets angry, people die and they die ugly, beaten into a squishy, slick mess.

The story opens with Nathan waking up to find an angry bull attacking his broken motorcycle. Narrowly escaping from the bull, an angry farmer and a now-dead but formerly very bitey dog, Nathan heads back to the caravan. The caravan, and Doc, inevitably must head toward the farmer and his young female child.

And Nathan must decide – in the land of the dead – whether to add to the number of bodies.

Kosmatka does a very nice job of getting the reader caught up in Nathan’s dilemma, doling out just enough information about Nathan’s world to keep up interest, but not enough to overwhelm. Nathan is a believable protagonist, cared for just enough that he prefers the Doc he knows to the devil he doesn’t. Nathan’s struggle is a difficult one for him and the reader.

Definitely worth checking out.

“The Art of Homecoming” by Carrie Vaughn shows why Vaughn is a bestselling author. Her series of werewolf books, starring a young woman named Kitty, might have conditioned the reader to expect a story that is considerably different from this story’s disgraced interstellar security detachment leader.

Following a possibly career-ending mistake of literally interstellar proportions, Major Daring offered her resignation to the Trade Guild and her former ship’s captain. It is not accepted because, thankfully for her, she’s actually rather good at her job. Instead, she is told to take a leave of absence, to go home for a couple of months. Therein lies the problem.

Major Wendy Daring doesn’t really have a home.

Raised with her sister Zelda as part of a collective family on a world made of cities, the Daring sisters escaped the accounting gravity of the family firm, each in their own way. Zelda found and married Mim. They moved to Ariana, an agricultural world with Mim’s brother, Tom. Wendy Daring went into Mil Div, seeing the worlds beyond her own, meeting a tiny part of the thousands of different species calling the galaxy home.

With a forced leave of absence, Wendy Daring travels for the first time to Zelda’s new home. The astonishing feeling of moving air that doesn’t herald a hull breech, sky that doesn’t end. . . They throw her for a while, but quickly become normal.

Major Wendy Daring finds out that she actually has two homes: her ship and the planet Ariana. She feels torn between contentment and adventure, between sister and ship.

In a way, this is a story we all have read before. Does the hero refuse the call to adventure? With stories of this type, it’s never the destination, but the journey that matters. And, in that, Vaughn succeeds for the most part.

Vaughn even manages to overcome the great difficulty of naming her spacefaring hero Major Daring. Even with a name like something out of the Golden Age of the pulps, Daring manages to be a very engaging character. Vaughn’s easygoing way with dialogue is used to full effect in this story, giving us a feeling that these are real people, making real choices.

There’s no werewolf in sight on Ariana, but this story definitely has some sharp teeth worrying at a memorable problem. Well worth reading.

In “Today’s Friends,” author David J. Schwartz shows us what it’s like after an alien invasion of sorts, when the human race still is around, just not at the top of the food chain any longer.

The Grays do not speak. The Grays don’t much like noise of any kind, except for music. And they might not even like that. They’re simply . . . fascinated with it. They also are telepathic, with no compunction against reaching into a mind and making it perform a song again and again.

Sometimes a bird’s heart will explode, or it will simply disintegrate under the attention of a Gray. Sometimes, a human makes the mistake of singing out loud. Or humming. Berto, an architect working on a proposal to create a living area for the Grays on Earth, didn’t even realize he was humming out loud until the Gray approached and reached into his brain.

When he recovered, Berto decided the only thing that made sense was to get away from the Grays as much as possible. Despite running into a trucker who believed the Grays were, in fact, God, Berto made it as far as South Dakota. It’s there, where he meets a formerly alcoholic bartender who says the Grays broke him down like they have so many others. Only this time, they put him back together, better than he was before.

Schwartz does a fantastic job with this story. Berto feels like a very real person in an impossible situation, making the best of what he can. The use of silence as a defensive reaction and a condition imposed upon humanity from outside works really well here.

I never really stopped to think about it before, but I’m pretty sure I talk more than most. I probably do. A lot. I kept imagining myself in Berto’s place, wondering how I would or could deal with the conditions he faced. That doesn’t often happen and I always take it as a sign of a gripping story. Schwartz, who currently is putting out the Amazon Serial The Gooseberry Bluff Community College of Magic (also a great read), does himself proud here. A definite pick up.

The question at the heart of “What is a Warrior Without His Wounds?” by Gray Rinehart does not, as might be surmised by the story’s title, concern a woundless warrior’s worth, but what a warrior would do never to have been wounded in the first place. Taking place in a post-Soviet Russia, Rinehart’s story is a fascinating look at the steps that some would take to ensure both the continuity of command and the continuity of a commander.

Captain Miroslav Ponomarenko lost an arm and a leg to an improvised Chechen explosive and awoke to a new life that could never measure up to what he had before he followed a foolhardy leader into an obvious trap. Instead of discharge into a dismal civilian existence, Ponomarenko is sent back to a dismal existence at home, where he was to report to his old school.

When he arrives, Ponomarenko quickly realizes that he is not there to become the victim of an elaborate practical joke but is there, instead, to be rejuvenated, his wounded body cast aside and to rise again in the form of one of the cadets. The cadet’s personality, like Ponomarenko’s old body, would be discarded and forgotten.

The process, Ponomarenko quickly learns, has been around for a long time and has resulted in several savants being quick-marched through the ranks in various government departments. If a man has enough highly placed friends, he will find that the end is not the end.

Ponomarenko, who was wounded not because he followed orders but because he went to rescue a foolish squadmate, has always protected the weak. If rejuvenated, he could still continue to do so, his leadership helping to keep other young soldiers alive. And all it would cost was the life of one cadet.

Rinehart, himself a USAF officer, brings a nice verisimilitude to the story, not only the reactions of a wounded soldier, but also to post-Soviet Russia. Both feel alive, even if suffering from severe wounds. The story brings with it some nice dialogue, well written and providing a sense of the Slavic, without resorting to sprinkling a few Russian words amongst the English as a shorthand for that language.

This is a nice story, involving and interesting. Definitely worth reading.

If you know anything about either of these next two authors, what I’m about to say might seem like the most obvious thing ever. “Yubba Vines” by Rudy Rucker and Paul Di Filippo is not your normal, average short story. It’s a little strange. And it all starts from what might be either a non-retroretro-futuristic or possibly tragically hip mobile food truck called Lifter.

Cammy and Bengt get a tip from Bengt’s friend Olala, who’s a countercountercountercultural obscurationist, and head out of the apartment for a big night out. Cammy’s not all that enthused about her big night out consisting of shuffling around a food truck, eating slops with slobs, while wearing a nice outfit. Bengt’s up for it and convinces Cammy it’s a good idea.

Turns out? Not so much a good idea.

The food is delicious. The service divine. The fat white guy singing reggae sings a revelation. The glowing desert is out of this world and drags Cammy and Bengt along with it for the ride. When they finally work up the ambition to leave, both of them stumble out of a door in the food truck that wasn’t there before, only Bengt has a little something extra: a chartreuse ear tag, like something an endangered humpback whale would wear on a long, but extensively researched migration.

After recovering the next night, Bengt goes to see his friend Olala, who’s got some disturbing news. Olala’s theory is that Lifter is a baited trap, using the lure of free food and good times and nice singing to bring in those who can get harvested later. And maybe letting some of the diners out if they’re tagged. Which doesn’t make Bengt feel any better.

What would? Probably some more of that delicious Lifter food. Which he goes to get. Leaving Cammy out in the cold, until she starts hunting up her hubby. Just in time to get transported, diner and all, into a disguised silvery spaceship staffed with human Quislings. The question facing Cammy and the now-corpulent Bengt isn’t so much can they escape, but with how much strangeness will they put?

Is the story odd? Is it well written? Does the sheer strangeness slither sublimely southward, shaking soliloquies from alliterative-addled appendages? Yes. Yes. And maybe. I’m not sure about that last one.

What I am sure about is that this story is definitely worth the time and trouble to read. Go do it.

So, for the most part, the issue lives up to its hype. Good stories. Nice action. A dollop of the New Weird and it all makes for a tasty read.