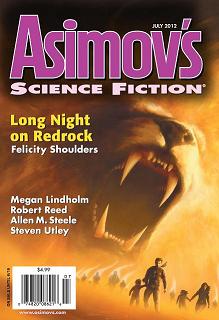

Asimov’s, July 2012

Asimov’s, July 2012

“Old Paint” by Megan Lindholm

“Alive and Well, a Long Way from Anywhere” by Allen M. Steele

“The Girl in the Park” by Robert Reed

“Kill Switch” by Benjamin Crowell

“Zip” by Steven Utley

“Bird Walks in New England” by Michael Blumlein

“Long Night on Redrock” by Felicity Shoulders

Reviewed by John Sulyok

A virus of aggressive nanites wreaks havoc to automated vehicles in Megan Lindholm‘s “Old Paint.” Caught up in the chaos are Suzanne, her children Ben and Sadie, and Old Paint, a family heirloom of sorts and a relic from a time of transition from human-driven to automated vehicles. “Old Paint” captures the charm of a good family movie with just enough action to keep things exciting.

Old Paint is one part loving grandfather, one part faithful pet, one part child, and one part childhood. The story begins small, then stretches its legs as it gains momentum. As events are put in gear, the destination becomes clear, but the journey is worth every second of the ride.

—

Jerry Stone is one of the richest men on the planet. Jerry Stone decides to leave the planet. Why he did this is up to his spokesperson, Paul Lauderdale, to figure out. Unfortunately, Jerry Stone is dead before the story begins and the answer becomes a mystery.

Allen Steele‘s “Alive and Well, a Long Way from Anywhere” is prefaced by stating it belongs to his Near Space series. That is exactly what it feels like. There is something missing, though, to make this story entirely captivating. The mystery surrounding Jerry Stone’s actions and a particular plot point are left mostly to the reader’s imagination. Perhaps “Alive and Well” requires more knowledge of the Near Space series to enjoy than Steele had hoped.

—

The world is overheating, people are pushed beyond their limits, but “The Girl in the Park” begins with an old man’s dream and regret. Suffering from memory loss, he is reminded by a recurring dream of a choice long past regarding a too-young girl heading in the wrong direction. The consequences of his decision impact more than his own conscience, branching out to take hold of his son and beyond.

Robert Reed weaves the intimate relationship between father and son into the world-gone-awry, creating a captivating plot in which all pieces serve a purpose, leaving the reader thoroughly fulfilled.

—

Jo and Chris live in a future where “genemodding” or “gengeneering” are commonplace. Parents — even middle-lower class ones — can opt to integrate talents and traits into their child’s physiology. For Jo and Chris, they have a predilection for music. For them, the question regards the child they want to have: should they assure their child’s musical talents or let nature take its course?

The problem with “Kill Switch” is that the inclusion of music as the primary interest for Jo and Chris feels arbitrary and is not ingrained in the plot at all. It feels like music could have been replaced with any other art or skill and the plot could have remained the same. That being said, Benjamin Crowell‘s joy of writing “Kill Switch” comes through in the attention to detail regarding music and the follies involved with unnatural human intervention.

—

The knee-high grass of a Pleistocene field is where the three-man crew of a small time machine unexpectedly find themselves in Steven Utley‘s “Zip.” The scientists are not as much stranded in time, but snagged on the very fabric of it, unable to move forward and causing reality to unravel as they move backward.

The terrestrial landscape is cast as alien with pre-historic farmers, giant sloths, and a horizon flaring up out of existence. The familiar is both distant and near, caught in the lives (possibly) lost and the fears and uncertainties ever-present in the hearts and minds of the crew. Utley captures these dynamics in the words of the narrator.

There are a few concerns, though: it is not explained who the crew are, who they work for, or what they are doing in and with a time machine. While these omissions do not hinder the story, they would have lent greater credence to the crew’s situation and the decisions they make. Also, the crew appear a little bit too calm for being caught in a time-conundrum. But these are minor complaints and should not deter anyone from reading “Zip.”

—

The life of a forty-year-old woman is captured in analogue; ever-changing love and serendipity capture her story in precise detail. Her marriage, failed, replaced by her ex-husband’s love of birds, she seeks to reestablish herself; to discover who she is. The lynch-pin is embodied by a peculiar specimen, which must be seen to be believed (or so one would think).

In Michael Blumlein‘s prose, ornithology becomes an undiscovered trove of descriptors, analogies, and a lens with which to view the world. It feels like a new language one must learn, for without it one is only listening to the song of reality without understanding the lyrics.

“Bird Walks in New England” is a beautiful story, less of science fiction than of human fact. If there is any complaint to be made, it is the allusion to medieval times via a knight-in-shining-armor metaphor which stretches too far and is not brought to an explicit end, creating a disturbance for the reader once it becomes clear the story is set in modern times. Armed with this knowledge, however, the tale functions flawlessly.

—

Felicity Shoulders tells very little about the residents of Redrock, a Mars-like planet. The story focuses on a family of four who farm aynids, a valuable crop. Peder and Lise are the parents of a son and daughter, and as former Marines they are willing to do whatever it takes to protect their children. When a stranger appears at their house hell breaks loose for the family, and they discover that aynids are not the only valuable commodity in their possession.

The players eventually find themselves in Sector 103, a section of desert prone to hallucination-inducing sandstorms, causing those caught in the maelstrom to confront their fears. While the premise teases a dark, introspective space-horror tale, the execution is rife with muddled prose, distorting the flow as if looking through a sandstorm. The climax is as uninteresting as the characters, and concludes in an expected way. “Long Night on Redrock” feels as though it was written to deliver the final, lackluster line of dialogue.