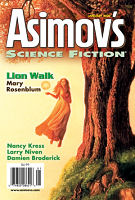

“Lion Walk” by Mary Rosenblum

“Lion Walk” by Mary Rosenblum

“Passing Perry Crater Base, Time Uncertain” by Larry Niven

“Bridesicle” by Will McIntosh

“Five Thousand Light Years from Birdland” by Robert R. Chase

“Messiah Excelsa” by E. Salih

“Unintended Behavior” by Nancy Kress

“Uncle Bones” by Damien Broderick

Reviewed by Robert E. Waters

The January 2009 issue of Asimov’s gives us two novelettes and five short stories. In Mary Rosenblum‘s “Lion Walk” we have a woman named Tahira Ghanu, a manager on a wildlife reserve featuring the flora and fauna of the Pleistocene Age. Set smack-dab in the middle of the US, this genetically transformed park has seen a rash of terrible murders, and our protagonist is thrust into the middle of the investigation. Not only does Tahira have to determine why young women are finding their gruesome deaths along the hunting trails of the lions which roam the park, but she must do it in such a way as to preserve the financial viability of the corporation which not only pays her salary, but keeps the park afloat with thousands of tourists each year. Needless to say, tensions are high as she seeks the truth while her bosses seek damage control. There’s nothing more to say without giving away vital clues, but Rosenblum is an excellent writer who keeps the pressure on by unfolding a mystery that’s brought to a very satisfying conclusion.

Next up is “Passing Perry Crater Base, Time Uncertain” by Larry Niven. This short-short tells of visitors to our solar system, and as they pass by, the automated systems on their ship observe the ruins of a base on our moon. What happened to the base, and why was it abandoned? Surely, they reason, the builders of this place must have moved on to bigger and better among the stars. But did they? Did we? Will we? That, I think, is what Niven is trying to say: that the assumptions of these aliens better be correct, for if we simply do nothing but visit the moon then stop, we will become nothing more than curiosities for species that were brave enough to try. This is a good warning, and Niven does well to raise it.

The award for the weirdest story goes to Will McIntosh’s “Bridesicle.” In the far future, women who have been in terrible accidents, or who have died from other serious trauma, are cryogenically frozen, so that years later, rich, lonely men may unfreeze them and pay the exorbitant price to bring them back to life. The price for this resurrection, of course, is marriage (or whatever the “perv” wants for his generosity). Dating for the dead and utterly pathetic! I consider myself a social liberal, but even I can’t get around the moral and ethical grenades in this story. When I started it, I could not imagine that the author would be able to salvage anything good from its premise, but I was pleasantly surprised at how touching and moving it was. The characters here are quite real and convincing as they seek a connection, any connection with another person, no matter how odd and morbid it may seem to us.

“Five Thousand Light Years from Birdland” by Robert R. Chase is a first-contact story that reminded me of Ted Chiang’s “Story of Your Life” and C.J. Cherryh’s Cuckoo’s Egg. A bird-like alien has wandered into our solar system, and scientists, linguists, and politicians scramble to ingratiate themselves to it so that they can understand its intentions. But when Screet, our birdman, has to leave, one of our own gets to go with him to play ambassador for the human species. Though quite satisfactory, the conclusion of this story is not all that important, in my opinion. What mattered the most to me was the discovery of the alien itself: its behaviors, its language, its physiognomy, its cultural and historical narratives. Therein lies the strength of the tale, and it reminded me of why I love science fiction so much.

“Messiah Excelsa” by E. Salih is a time-travel story set in the mid-1700s. Our traveler goes back to meet the great Antonio Stradivari, maker of the Stradivarius violin, and to hopefully find (and steal) the master’s own personal instrument, the so-called “Messiah” of violins. Normally, I’m quite fond of stories with a strong musical component. But alas, this one just doesn’t work. It’s a classic case of style trampling plot – what little plot there is. The author writes in that over-wrought, excessive manner in which tales of the time were often told. There’s far too much description of what people are wearing and what they’re eating, and the loose, almost cavalier manner in which our narrator whips out Italian phrases made me scratch my head and wonder why a character from the modern age would tell his tale in such purple hues. Then once we reach the interesting parts – those dealing with making the instruments – the narration falls into a kind of college lecture, a recitation of one historical fact after another, with little or no energy.

“Unintended Behavior” by Nancy Kress is one of those stories that you read and then pray never happens. Here, Annie lives in utter oppression, spending day after day in a house with all the technological amenities of the time: Televisions and stoves and refrigerators and security panels, each with their own voices, telling Annie what to do, what to cook, when to cook, what to buy, when to buy, what to think, and on and on. These gadgets also serve her husband, who sits on his “asshole” throne at work, monitoring her every move. And now their dog, Beowulf, has been fixed with a device that monitors brain waves and gives human speech to his thoughts. But the time has come for Annie to shrug off these shackles and take control of her life. Will she succeed? With the unintended behavior of Beowulf, perhaps she will. Kress is a pro, and this story is no exception. Certainly not her best, but nevertheless quite satisfying.

Damien Broderick wraps up the issue with “Uncle Bones.” Here we have a society where medical technology has discovered a way to keep people alive through nano-bot injections which revitalize the flesh. This new medicine has created a kind of zombie sub-class called Stinkies, so-called because of the bacterial decay of their internals and the nasty odor thereof. Our protagonist and his uncle, a veteran of the terrorists wars, have to deal with not only the physical limitations of their revitalization, but also the social stigma, prejudice, and scorn that goes along with being a member of the living dead. It’s a good story with a nice ending, but it isn’t great. Broderick is a decent writer so he keeps it fairly interesting throughout, but there’s nothing really new here which adds to the nano-tech or zombie sub-genres.