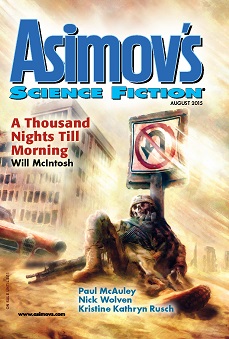

Asimov’s, August 2015

Asimov’s, August 2015

Reviewed by Jason McGregor

This month’s issue of Asimov’s seems to have a theme and that theme is family and love. The most successful stories are the two on the extremes: the most appealing story of retro-engineering and crypto-zoology and the most horrific story of alien invasion. The less successful are the generically dystopian (or slightly positive) run of the mill VR, genetic-experiments-gone-wrong, badlands-after-the-collapse, and time travel stories. There are no positive visions of the future in this issue.

“No Placeholder for You, My Love” by Nick Wolven

There’s no way to summarize this story at all without spoiling half of it, but the end is safe. There is frequently romance in SF but this is SF in romance: we are told a romance story comparing some of the pros and cons of the single vs. married life which, for about a third of the story’s length, showed no signs to me that it was speculative at all (and then seeming to be some kind of slipstream) before getting to the vicinity of the halfway point and revealing that this was another “message in a bottle” story: a virtual reality/AI simulation story. Had this been written as hard SF, there are signs that I would have taken literally which indicated the VR nature of the milieu but, given how this story and many others like it are written, I took one of the most obvious clues as an annoying stylistic tic that I assumed would eventually be revealed to have purely symbolic/thematic meaning. Further, while mental gymnastics could produce an argument that the decoherence at the end was thematically justified, it really seemed like an illogical and arbitrary amplifying of the drama because it was just time for the story to start its rising action. Even if other readers don’t stumble the way I did, the gist of it all is: girl meets boy, girl loses boy and meets many other boys and girls, girl meets boy again and… and I promised the end was safe so you’ll just have to read it if you really want to know.

“Two-Year Man” by Kelly Robson

This seems to me to be a technically well-executed sweet and vicious story. We’re introduced to a slow-witted but kind-hearted janitor working in a sort of dystopia where everyone is segregated (somewhat implausibly in the details, which are held too late in the story) into rigid classes, of which he’s in the lowest. He works in what seems to be a genetics lab and finds a sort of bird-baby in the garbage and sneaks it out to his home where he intends it to be his and his barren wife’s child. (She sold her ovaries because she needed the money.) His wife is not pleased. In this state of indeterminacy, he goes back to work, leaving the wife and entity at home, alternately imagining good and bad outcomes while we observe more of his working conditions. It ends in that same state of indeterminacy in an action-sense, but comes to a philosophical resolution—or a psychological resolution: a literal resolve on his part—leaving it neither unduly pat nor annoyingly lady-and-the-tigerish. But I fail to see how this can be read as anything but a “women must be mothers, pro-life, anti-science” story. There are seeming counter-indications: the protagonist is “simple” so if he thinks his unmaternal wife is “broken” then that’s his opinion. But nothing in the story contradicts his opinion. Abortion is never mentioned, but we are meant to be repelled by the practices in the story and everything from fully viable babies to early embryos are depicted, leading one to carry the thought further. And we don’t do science like this—this is a dystopia after all—but science seems to be equated with incinerating failed human genetic experiments beyond the test tube level. Now, any opinions expressed in a story are fair game if aesthetically executed and I may be wrong about this story anyway but, if not, it’s just not what I would expect to find in Asimov’s. (It also seems to be an anti-class, especially anti-elitist, story but it does not surprise me to find that in Asimov’s.)

“Wild Honey” by Paul McAuley

Stop me if you’ve heard this one before. Civilization has collapsed, antibiotics don’t work, all the original bees have died off, but an old woman maintains a colony of the successors of bees when a gang of outlaw bikers tries to take her stuff and violence ensues. What seems to be a meme in the air figures in this, in that the biker leader is a Fixie/Neo/whatever:

They’d been designed for space travel, neos. Tweaked so that they stopped growing at around eight years old. The idea had been that they would need fewer resources and could live in smaller craft than base humans, and although the Collapse had ended the old dreams of making new homes beyond Earth, they’d survived and thrived.

The “old dreams” seem to have ended, at least for much of SF and society, even without any collapse, so how would neos ever come to be? Regardless, this presents the ludicrous image of the cigar-smoking toddler in Who Framed Roger Rabbit? being the threatening leader of outlaws. And this is the usual hodge-podge of having drones “printed from fungal mycelium and coated in bacterial cellulose and wasp-spit proteins” and other such things mixed with the Wild West or medieval times like so many other post-“Collapse” stories despite it having been presumably 40-100 years since. And, without specific spoilers, the ending made little sense to me, seeming to be a zero-sum nihilism but perhaps intending to be an “in with the new” more than the “out with the old… and to hell with it” that it seemed to be.

If you’re going to write this story yet again at this point, you need to create something truly remarkable. This isn’t.

“Caisson” by Karl Bunker

In a nice antidote to the previous story, we receive a tale of creation and life, though we have to go back to 1871 to get it. The story opens with one Polish immigrant meeting another and getting a job working on the Brooklyn Bridge or, more precisely, in a caisson under the river on the first part of the bridge. Some readers of an infodump-phobic persuasion may not be as fascinated as I was, but the story does an excellent job of weaving its tech into the human narrative of the characters meeting and making their lives. And while all this engineering and background science makes the tale feel quite science fictional this is only real tech (even old tech). It bears a resemblance to the first story in that it takes two-thirds of its extent to fully reveal its (unsurprising) crypto-science fictional nature. While that end is thematically satisfying, it seems somehow lacking in other terms—a lot of windup for a very short pitch. But I still enjoyed this one for its technical and historical texture, its nicely sketched and likable pair of characters, and its positive approach. I suspect I won’t be alone.

“The First Step” by Kristine Kathryn Rusch

The absent-minded professor invents a time machine for the sole purpose of going back to one moment in his lifetime in this very short story. I can’t say much more about it without stepping on the story’s toes so I’ll just say that this will likely work very well for some and not for others.

“A Thousand Nights Till Morning” by Will McIntosh

Boy howdy, is this novella a mess. If being utterly gripped and emotionally wrung out by the end of a story, along with having several moments of actual sfnal ideas, counts as a good story, then this was indeed that. If a very awkward, shaky start, odd elisions past crucial scenes, a narcissistic protagonist whose author doesn’t let him be anything else even after the protagonist realizes it, a completely pointless element underlying the whole story, and a “you can’t fire me, I quit” ending and many other things (including not just the protagonist losing control of himself but inexplicably failing to clean up as quickly as possible) counts as a bad story, then this was indeed that.

We are on Mars for (explained after it should have been) the purposes of deflecting an asteroid which will pass nearby from intersecting with Earth when we receive word that aliens have invaded and wiped out most of the human race with plagues. The descriptions of these aliens via hearsay are pretty inexplicable and the neat thing is that they actually make sense. What doesn’t make sense is why a species capable of adapting itself to anything would need to invade Earth rather than, say, adapting to Pluto and all the other rocks throughout the galaxy. Our protagonist is a psychologist with an anxiety disorder who, on receiving news that the latest calculations show the asteroid missing Earth, jokingly suggests that, rather than deflecting it away, they deflect it into Earth to screw up the invaders. The motion is adopted, despite the horrors of killing off so much earth fauna and surviving humans. However, while it does put a serious hurting on the invaders, it doesn’t wipe out either them or us completely. It does enable the surviving humans to contact Mars and Mars sends out a ship to investigate conditions and perhaps bring back supplies and useful humans to increase the gene pool. (One of the problems is that one gets the idea Mars and Earth are not much further apart than the moon and Earth. Another is that Chicago and Mars seem tiny.) The rest of the story takes place on Earth and, for once, while skirting what I thought would be a mushy peace and forgiveness message, there’s actually some slight hard-nosed attitude and catharsis amidst the overwhelming tragedy. I wish somebody had edited all the rough edges off of this story but it’s still worth it overall.

Jason McGregor‘s space on the internet can be found here.