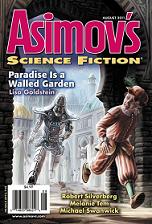

Asimov’s, August 2011

Asimov’s, August 2011

“The End of the Line” by Robert Silverberg

“Corn Teeth” by Melanie Tem

“Paradise is a Walled Garden” by Lisa Goldstein

“Watch Bees” by Philip Brewer

“For I Have Lain Me Down on the Stone of Loneliness And I’ll Not be Back Again” by Michael Swanwick

“We Were the Wonder Scouts” by Will Ludwigsen

“Pairs” by Zachary Jernigan

Reviewed by J. P. Wickwire

Taking place in the familiar world of Majipoor, Robert Silverberg’s “The End of the Line” is a tale that puts the human and Metamorph–or shapeshifter–racial tensions up front. At least, that’s what it tries to do. In reality, readers need to slog through a few pages of infodump to get to the heart of the story. And even if they last that long, they still need to survive the crush of foreign names and places.

Thankfully, once these things level off, Silverberg gives readers an opportunity to immerse themselves in a well-established world, and a story that almost always knows where it’s going. Following a braid of three characters–the eccentric professor Mundiveen, the curious-but-duty-bound Staimot, and the semi-power-obsessed Coronal Lord Strelkimar–“The End of the Line” is a portal into a completely developed, but somewhat confusing world.

Perhaps better suited to predicated fans of the Majipoor universe, “The End of the Line” still presents itself as a satisfying read for the patient reader.

Yet another story that explores racial tension between an alien population, and that of the human world, Melanie Tem’s “Corn Teeth” is as disturbing and innocent as its title implies. This wonderfully frenetic hash follows the, ahem, “heartwarming” tale of an Alayayxan family on their quest to adopt a pair of human siblings. Sonya, one of the children in question, has grown used to the strange multi-limbed, grayish group of three that will soon become her parents…but only because she thinks that upon being adopted, she’ll become Alayayxan herself. When she discovers that no, her hair won’t fall out and she’ll keep her human corn-shaped teeth under Alayayxan care, things go horribly awry.

Tem’s writing rambles forward in Sonya’s childish and scatterbrained voice for the entirety of the piece. And this isn’t a bad thing. “Corn Teeth” is rooted almost entirely in emotional impact and the artful insertion of jagged edges; full of language that tumbles over itself, and a story that’s so familiar it seems alien. But it’s not a happy tale, and hosts an appropriate, but terribly abrupt ending that severs the emotions that continue to run high.

In Lisa Goldstein’s “Paradise is a Walled Garden,” protagonist, Tip, is a boy–no wait, a girl dressed as a boy–working as a factory hand in an alternate Elizabethan era filled with steam-powered homunculi: sort of mechanized humanoid robots. But when one of the factory homunculi has a violent glitch, things take a strange turn indeed. Suddenly thrust into the company of Queen Elizabeth and the strange culture of the Middle East, Tip’s life is…well, changed, obviously, but not much else.

Tip never really finds her voice, despite the fact that she oozes plucky heroine. Or maybe she does find her voice, and it’s just poorly executed and/or naturally annoying. The storyline has potential, but is plagued with lifeless characters and unfortunate pacing. The world itself is complete though, and one can definitely see other stories happily growing in the same universe.

Full of characters that kind of archetype all over each other, and dialogue that should’ve included phrases like “And I could have gotten away with it too, if not for those meddling kids!,” “Paradise is a Walled Garden” saw the light of potential, but for some reason, turned away.

Philip Brewer has created a monstrosity with his story, “Watch Bees.” Hmmm. Watch bees. They’re these pesky, but useful creatures that guard your farm. Genetically modified, sure, but still organic enough to produce honey and reproduce. Oh, and they also function as awesome, killer attack creatures that destroy anyone who causes hardship and doesn’t share the farm family’s DNA.

David shows up at one such farm, asking for work. The farmer, though skeptical, allows him to help out around the farm. But something isn’t right–both the farmer and Brewer’s readers know it. Are David’s motives really as innocent as he claims? And is his blossoming love for the farmer’s daughter, Naomi, just a ploy to get what he wants?

“Watch Bees” takes place in an utterly engaging, but strikingly off-kilter world; full of characters doused in human potential, and whose voices establish themselves early on. As an author, Brewer exhibits full control over, not only the world he’s created, but of his characters as well.

Easily one of the stronger, if not the strongest story in this issue of Asimov’s, “Watch Bees” is forceful and paranoid–a combination that isn’t easy to gloss through.

The third story in this issue to deal with alien/human tensions, Michael Swanwick’s long-titled “For I Have Lain Me Down on the Stone of Loneliness and I’ll Not be Back Again,” presents a rather confrontational option for humans who oppose the alien occupation: why not just threaten the outsiders with violence, and then kill them off?

Swanwick’s protagonist is an American seeing the sights of Earth after winning a ticket off-planet, most likely never to return. He ends up in Ireland, where he meets the fiery Mary, a musician with a stubborn will and strong sense of national pride. But Mary may be a little too nation-happy for our American friend, and she definitely has a violent streak to match.

“For I Have Lain Me Down on the Stone of Loneliness and I’ll Not Be Back Again” is steeped in the strange juxtaposition of Irish folklore and alien/human co-existence. Definitely aimed at those readers who aren’t tired of intergalactic racial conflict after two other stories in the same vein–or readers who really love Ireland. Though the characters are strong, and the story is unique-ish, there isn’t much of a hook for readers.

In Will Ludgwigsen’s “We Were the Wonder Scouts,” main-character Harald’s parents don’t approve of his wild imagination and tendency to see things that only exist outside the lines. They even destroyed his beloved backyard world of Thuria. Thankfully, Harald soon discovers a group of boys just like himself–the Wonder Scouts–and under the tutelage of the mysterious but wise Mr. Fort, the boys embark on a life-long journey to find the worlds hidden in every day life.

“We Were the Wonder Scouts” is a fun, uncomplicated sort of read that basically recounts one adventure with the world’s coolest boy scout troop. The characters are cheery, and the plot is short and sweet. Though protagonist Harald’s personality and voice don’t match all that well, and the loveable Mr. Fort often seems more like a fortune cookie than a mentor (“Ghost stories, my boy? They’re just the gossip of the dead.”), it still works. Why? Because Ludwigsen never pretends his story is anything else than what it is. And it’s just a fun, quick tale of childlike wonder.

One has to wonder if even author Zachary Jernigan knew what was going on in “Pairs.” Arihant is one of two humans still inhabiting a human form. He spends his days trying to turn himself into a knife, while his counterpart, Louca, prefers animal forms. In any case, they’re both enslaved by some sort of non-human hunter, and are forced to ferry the ghosts of dead humans to potential buyers. Kind of a Davy Jones of the stars sort of thing–which, of course, brings up all kinds of questions regarding human nature and the essence of a human soul.

Though “Pairs” seems to have a lot of potential, much of the story is too intangible to enjoy. Jernigan’s concept is so abstract that he provides nothing for readers to grab onto, and in consequence, they are left largely groping in the dark after characters who frustratingly may or may not actually exist. “Pairs” tries to be high-brow, but unfortunately falls into the muddy territory of poorly explained and far-flung space exploration.