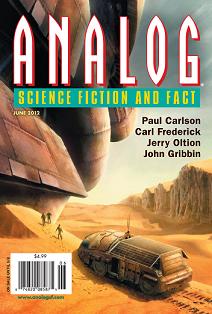

Analog, Science Fiction and Fact, June 2012

Analog, Science Fiction and Fact, June 2012

“Crooks” by Paul Carlson

“Titanium Soul” by Catherine Shaffer

“The Fine Print” by Michael Alexander

“A Murmuration of Starlings” by Joe Pitkin

“An Ounce of Prevention” by Jerry Oltion

“Darwin’s Gambit” by Emily Wah

“A Reasonable Expectation of Privacy” by N.M. Cedeno

“Food Chained” by Carl Frederick

Reviewed by Nader Elhefnawy

The June 2012 issue of Analog begins with Paul Carlson‘s novelette “Crooks.” It Is Carlson’s third story about near-future trucker Claude Dremmel and his friends (the previous two being “Shotgun Seat” in the magazine’s July-August 2008 double issue, and “Rule Book” in the March 2011 issue). This time around Claude and company take on a fuel theft ring in a tale of computer hacking, high-tech surveillance, luxury survivalism and political corruption. “Crooks” heavily references the previous Dremmel stories, but I found it easy enough to follow without having read them. A bit more problematic is the uneven pacing and loose plotting, but that is a reflection of the novelistic writing, which does have as one benefit strong world-building.

In the next story, Catherine Shaffer‘s “Titanium Soul,” Connie, a sociopath living in the near-future who has spent her whole life using people, finds herself forced to choose between jail time and submission to the implantation of a “prosthetic conscience.” She chooses the latter option, which turns out not to be the end of her problems, but the start of a whole set of new ones as she confronts new needs, and new inhibitions. It’s an interesting idea, given compelling treatment by Shaffer, whose story is easily the most character-centered, and human, in this issue.

Michael Alexander‘s “The Fine Print” is a laboratory-set story of scientists dealing with the first contact situation raised by the discovery of a meteorite in Antarctica. By contrast with “Titanium Soul,” which emphasized Connie’s experience to good effect, “Print” is slight on storytelling, and heavy on scientific deal, particularly protagonist Sophie’s work as a mass spectrometrist. Indeed, the tale itself comes off as a framing device for its characters’ musings on one way in which a technologically advanced species might reach out to other intelligences. Unfortunately, neither the characters, nor those musings, were sufficiently interesting to support the story.

Joe Pitkin‘s “A Murmuration of Starlings” is set in the midst of a pandemic spread by starlings, with the result that the expertise of biologist Evelyn Cole (a specialist in that species) is suddenly drawn out of academic life to help contain the spread of the disease. In the course of that fight what begins as a tale of medical disaster turns into something quite different, with the result an interesting fusion of two different science fiction subgenres.

In Jerry Oltion‘s “Ounce of Prevention,” eight year-old Tina of the lunar Copernicus colony meets her grandfather in person for the first time. As it happens, grandpa is a crotchety senior citizen who is not just uninhibited about vocalizing his earlier generation’s bigotries, but finds plenty of occasion to speak them (as well as much else to annoy him). Naturally, the visit quickly turns unpleasant for all involved. Some of the elements are not totally convincing, like the attitude toward sterile environments, given the advent of the “hygiene hypothesis,” and the dating of grandpa’s particular quirks. (One might imagine that by the time when an eight year old could have spent their whole life on the moon the prejudices associated with old men will have changed from those we take for granted today.) Still, I was entertained by Oltion’s presentation of a stew of ideas and conflicts (a generational gap and a clash of cultures; the collision of rugged Golden Age expectations about space colonization with the course such efforts would be far more likely to follow; a consideration of illness and health and how technology might change our approach to them) in this children’s story decidedly not for children.

Also utilizing the “family drama in space” theme is Emily Wah‘s “Darwin’s Gambit,” which is set aboard a space flight carrying the first human beings who will set foot on Ganymede. Centering on an adolescent who has to overcome an obstacle (agoraphobic Amber) and prove themselves to doubting adults (psychologist Dr. Kathryn Vickers, who is dubious about Amber’s suitability for the mission), it is basically a YA story related through an adult’s eyes, Amber’s experiences being presented through the point of view of her mother Elianna. While not a bad read, it fell a bit flat for me. The twist is unsurprising, and that event (which should have been the story’s climax) is simply retold to Elianna by other characters after the fact rather than dramatized, while the storytelling, characterization and world-building lack the special flair that would have elevated “Gambit” above its essentially familiar material.

In N.M. Cedeno‘s “A Reasonable Expectation of Privacy,” private eye Pete Lincoln has regained consciousness fifteen years after being shot, to find himself in a world where a combination of technological, cultural and legal changes have made privacy a thing of the past in the most literal sense. The buildings we live in are made of transparent material, and anyone so much as keeping a blog is legally regarded as a public persona, a situation which has diminished some problems, and naturally exacerbated others. Lincoln’s career has predictably suffered (in a world where privacy is absent, the market for such detective work as he offers has shrunk), but he remains on the job, and gets a new client at the start of the story, which soon enough has him investigating a murder of a kind that can only take place in such a social milieu as this. Cedeno’s treatment of his theme is a bit over the top (especially in its compression of the time frame in which such profound change might happen), and Lincoln’s adventure is basically in line with the conventions of crime fiction of this type, but it does make for an entertaining approach to a very real issue.

The last piece in this issue, Carl Frederick‘s novelette “Food Chained,” is set aboard a manned expedition to a planet circling the allusively named star Rolf 124C, sent there to investigate the possibility of intelligent life. The three astronauts participating in the mission find themselves stranded, a situation that brings them into contact with an intelligence of the kind they had come to find – though not in the way they had hoped to find it. “Food Chained” moves along briskly enough, and touches on a number of interesting issues (like space environmentalism), but the characters aren’t particularly engaging, and the basic plot elements felt overly familiar, while the story seemed more convoluted than it needed to be.