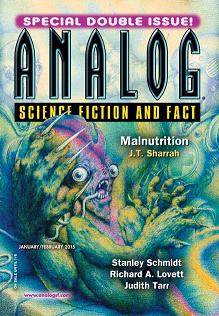

Analog, January/February 2015

Analog, January/February 2015

Reviewed by Martha Burns

Analog begins the New Year with a double issue chock full of missteps and missed opportunities. The first of these is the novella “Defender of Worms” by Richard A. Lovett. Brittney, a sentient AI, has a new host body in this installment of an ongoing series. Brittney had been living in Floyd, a frontiersman in space, and she’s now the double consciousness of a socialite whose mother had Brittney implanted to keep an eye on her wayward daughter, Memphis. Brittney and Memphis flee through the American Southwest trying to evade the Borg-like Others, who want Brittney to join them. On the way, Brittney comes to appreciate what it is to inhabit a woman and Memphis not only learns essential survival skills, she comes into her own, or at least that’s the intention. There is only one scene in the novella where Memphis attempts to give Brittney insight into being a woman. Memphis explains that even though she’s been cleaning off in melted snow during their trek, she needs a shower because her hair is “like greasy straw. And everything itches. Not to mention stinks.” Oh dear. The story does not, in short, deliver on what it promised. We’re promised significant insights into gender differences and this, sad to say, is all we get. Nor do we see Memphis come into her own in any meaningful sense. Early on, Brittney has Memphis stand in her underwear before a mirror. Brittney sees “decent shoulders, toned arms and legs: beach-buff, but not necessarily truly fit, as opposed to show-off fit” and Memphis does get significantly stronger during her time in the wilderness. Her key epiphany, however, is that being a socialite is shallow. One feels there should be more, much more.

I recommend the novelette “Malnutrition” by J. T. Sharrah, though not without caveats. An alien who regards being force-fed as rape is in critical condition after an assassination attempt. How will the Terrans keep the comatose alien alive if they can’t feed him, and who tried to kill him? This conundrum provides Sharrah the opportunity to focus on the pugnacious banter between Hardesty, the major of the colony where the assassination attempt occurrs, and Yulix, a rapscallion intergalactic trader who speaks the alien’s language and is aware of their customs. The fast and funny quality of the banter, along with the colony’s name—Haven, the name of a colony in Joss Whedon’s Serenity—hint at the story’s lineage and there are gems worth of Whedon, such as Major Hardesty referring to the alien’s ship as the Unpronouncable. The only quibble is that Sharrah spends far too long laboring over the alien’s attitude toward food as if the reader couldn’t possibly understand. Sharrah does an excellent job of taking a peak inside the alien’s head early in the story so that we can appreciate his repugnance at the idea of a state dinner. That’s all we need, yet aside from these too-frequent moments of not trusting the reader and making the otherwise intelligent character look a bit dim, the story is an entertaining, lighthearted yarn.

“Just Browsing” by Stephen Lombard goes awry in so many ways that it’s hard to know where to begin. Aliens, for no very clear reason, want to visit the library in the town where Kelly presently lives and used to share a home with his now-estranged wife, Angela. Angela is the ambassador from Homeland Security who is supposed to meet the aliens, yet she finds them too creepy and so asks her estranged husband, a high school history teacher, to do the job. Soon we come to understand the real reason Kelly is there. With the help of some thoroughly wooden dialogue, Kelly teaches the aliens about relationships, chess, and the mystery of Fermat’s last theorem, which is no longer a mystery in this reality, as it was solved by Andrew Wiles. Needless to say, Kelly’s brilliant efforts reunite the couple and cause Angela to want to have his child. Baffling. Utterly baffling.

I recommend “The Great Leap of Shin” by Henry Lien for its epic weirdness. A devastating earthquake is coming and Emperor Shin’s chief engineer, a eunuch, has a plan to stop it by shifting the Earth’s tectonic plates. His plan involves millions of men jumping at the same time. The men, cramped together and miserable, are starving as they await the engineer’s command. Meanwhile, the people of Pearl send a group of three teenaged dancers to persuade the engineer that this is a bad plan and will cause a tidal wave that will destroy their island. The tension mounts as the teens’ dance turns into a martial arts extravaganza designed to kill the engineer, but their lead dancer may not be able to do the deed because he develops empathy for the eunuch, who not only has no testicles, but no penis as well. Thoroughly bizarre and engrossing.

Dave has been asked to help a research team in the Antarctic communicate with an alien species. The species is deaf and has poor vision and Dave, who is also deaf and has poor vision, is chosen for that purpose. Let’s stop here and ask why Dave would be able to help. He has a cochlear implant that helps him hear and he has some vision, though it is weak. He doesn’t have access to any other sense, so why would Dave have anything helpful to add? Dave does eventually help, but it isn’t because of his senses, and he almost doesn’t succeed because of the ubiquitous government agent who wants to stop the project the moment the team begins to make headway. Yet what is most unsatisfying about “Usher” by Jay Werkheiser is that the odd misstep is startlingly easy to avoid. Dave was, before his senses began to fade, a scientist. It would be so simple to have him brought aboard for that reason and to have his disability (it is actually the tech of the implant rather than Dave’s disability per se) help solve the communication gap. The story would still have had a stereotypical bad guy, but at least the premise of the story would be solid.

In “Ulenge Prime” by Chuck Rothman, an African dictator abducts his wife. His destination is his space station, Ulenge Prime, that he’s killed so many to create. He’s trying to outrun a coup, but also to impress his wife, who only accepted his marriage proposal in the first place because he promised her the stars. She warned him then she would never love him and makes good on it later by taking one of Ulenge’s rivals as her lover (we’re assured the lover only did this to get back at Ulenge). Ulenge comes out the partial hero in all of this in a move that, given the context, isn’t that odd. What is odd is that this is made possible by the wife’s characterization, who it doesn’t take much acuity to realize is being blamed for the whole fiasco.

Mark, a researcher on an off-world colony, mourns the woman who refused to come with him. Mark, back on Earth, had himself downloaded so that he could travel to the colony, but Anne, after initially saying she’d be downloaded too, wouldn’t go. Back on Earth, the original Anne leaves the original Mark as well. On the colony, Mark can’t pull himself out of his funk and begins cutting himself until Alice gives him another option: come into the wilderness and become someone new. The premise, though strong, is undercut by the difficulty of empathizing with Mark, who is a passive character with little insight and no development per se. Mark makes it to nature, but only because he’s following Alice, hence he never fixes what got him into trouble in the first place. We have little hope for Mark and that does not seem to be the response David L. Clements wants us to have in response to “Long Way Gone.”

In a near future, a group of geezers drink up and watch a moon landing in “Orion Rising” by Arlan Andrews, Sr. They grouse about the good old days of Apollo in a lighthearted (and unfortunately lightweight) ribbing at modernity with a few throw-away references to Heinlein thrown in for good measure.

In “The Yoni Sutra” by Priya Chand, Shalina is a young woman in charge of showing Gayatri, a new hire, the ropes at work. They are dissimilar in a number of ways. Shalina is newly married, Gayatri is divorced; Shalina is quiet and controlled, and Gayatri laughs loudly; Shalina, like most women, has a chip that shocks any unauthorized man who touches her, and Gayatri is chip-free. Sadly, the chip turns out to be more of a gimmick than a means to analyze women’s sexual vulnerability. Shalina’s relationship with her new husband, her burgeoning sexuality, her feelings about child bearing, even her relationship with Gayatri have nothing much to do with the chip except that the predictable happens, which is that Gayatri suffers from an attempted rape and Shalina shocks a man who dares look at her when she was in a bad mood.

“Why the Titanic Hit the Iceberg” by Jerry Oltion is as over the top as they come. Earth is on the fast track to becoming uninhabitable, but the very rich have a luxury space station to go to, complete with lawns, restaurants, and the major’s Humvee. Tough-talking Tony works on the station, keeping it in orbit, and blond, perky-boobed Sandra helps maintain the environmental systems. Before long, both develop a deep antipathy to the wasteful residents, who they call piggies, and they decide to do something about it. The story is so over the top in its disdain for consumerism and egregious consumption that the intention is likely comic, but it isn’t quite light enough to be funny and not dark enough to have any heft.

In “Fool’s Errand” by Judith Tarr, a stasis tank on a spaceship fails. It contains a horse that Dr. Nashir is transporting to a planet where his primary objective is to research a mysteriously vanished civilization. Marina is jealous of his project since she’s an academic who couldn’t find a researching job, but her former life on a ranch and present position tending cargo on the trader ship means she is personally and professionally invested in whether the pregnant horse, Wahida, survives the jump through space. Marina’s eventual solution to both the horse’s fate and her own is entirely too simplistic and includes a gratuitous jab at drug companies (I, for one, do not think my anti-epileptic drug is a conspiracy). But if you can overlook one more swipe at Big Pharma, you’ll find the story sweet.

In “Samsara and Ice” by Andy Dudak, a soldier in a war that may be long over is held in stasis so that he can be awakened every several hundred years or so to repeatedly kill an enemy soldier, who is reincarnated in time for the next go around. A primitive society of fey keep the charade going which, for them, becomes a religion that gives their society stability. They term the soldier who does the shooting The Sleeping God and the soldier who does the dying The Dying God. Things change when The Dying God attempts to communicate with the man who’s killed him so many times. The story is about the conflict between duty and choice and the horror involved in each. Recommended.

“Marduk’s Folly” by Sean Vivier is a too-easy paean to individuality over conformity. An insect-like alien suggests there is life on other planets, which violates received opinion. In this society, if you offer a dissenting opinion, your colleagues turn against you and female insect-creatures will not have sex with you. What is so unsatisfying about stories like this (ones where the lone genius is celebrated over the ignorant masses, not stories where female insect-creatures refuse sex) is that scientific communities do not reach a consensus by counting the raised hands. Science doesn’t work this way and one would hope science fiction writers would be willing to plumb the much stranger ways in which fact is continually debated and reshaped in science.

“Unmother” by Alex Wilson is undeniably creative, but it is also a bit of a mess. An alien presence in a human host brain scopes out a suspicious invader. This clever alien presence is part of a larger collective, each of which go out to the brain, collect information, and return to share it with the queen-bee-type Mother. The clever daughter is, however, deformed. She can’t join with Mother and so needs a creative solution so that she can warn her fellows of the impending disaster. The story plumbs the sadness of being an outcast and the necessity of free access to information, even if that information comes with a heavy price. All of this is well and good, but there are simply too many beats that I felt were meant to be significant that I couldn’t make sense of. It’s supposedly significant that the host is female (this gets an exclamation point in the story) and it’s also apparently significant that the invading cell is termed Brother. I couldn’t tell what was going on here, nor did I entirely understand what Brother was up to. I was also never sure what happened to the host brain when the clever daughter cell who becomes the Unmother solves the mystery.