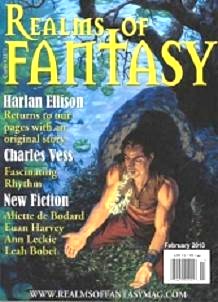

Carl Slaughter and Nathan Goldman take a look at the February issue of Realms of Fantasy.

Carl Slaughter and Nathan Goldman take a look at the February issue of Realms of Fantasy.

“How Interesting: a Tiny Man” by Harlan Ellison

“Mister Oak” by Leah Bobet

“The Demon of Hochgarten” by Euan Harvey

“Mélanie” by Aliette de Bodard

“The Unknown God” by Ann Leckie

Reviewed by Carl Slaughter

This issue of Realms of Fantasy is a disappointment. Only one truly worthwhile story.

Never mind the title. “How Interesting: A Tiny Man” by Harlan Ellison is not about a tiny man and not about a man considered interesting. Not considered interesting in the second half of the story, anyway. It’s about the people who react to the tiny man. In the first half of the story, the tiny man is viewed as an oddity. In the second half of the story, he is viewed as an abomination.

There is a cruel surprise ending, one that is not consistent with the rest of the story. There is also an alternate ending. The second ending fits the story better, but is only a little more satisfying. The story offers no explanation for the motive or method of creating the tiny man. Nor does it offer a legal basis for both of them being considered criminals.

The last word of the first ending is “Mother.” This seems to come out of nowhere, since we have not learned of the tiny man’s origin or even the existence of this mother. No doubt the author has a reasonable explanation for this, but it escapes this reviewer.

The meaning of the poetic intro and its connection to the story also escapes me: “Across the endless vista of human experience, the voiceless whispers of remarkable stories rustle on the wind, and many of them escape our understanding because we do not know the many languages that fill the silence.”

The somewhat chatty, almost century-old storytelling style is creative and refreshing: “I can’t remember why I wanted to do it, not at the very beginning, when I first got the idea to create this extremely tiny man. I know I had a most excellent reason, or at least and excellent conception, but I’ll be darned if I can now, at this moment, remember what it was.”

There is no development for the main character. Other than the fact that he made, cares for, and tries to protect the tiny man, we learn nothing about the creator. The tiny man is an interesting and impressive character, but doesn’t receive quite as much development as his character deserves.

This is an enjoyable story, but it is no gem. It is not higher quality than the multitude of stories competing against it, nor is it more memorable, nor does it make a greater contribution. It’s just a nice little story, if at times difficult to fathom.

“Mr. Oak” by Leah Bobet is a fable/allegory about a tree in love with a woman. First it imagines itself being a man, then imagines her being a tree. When her lover leaves her, she wraps her arms around the tree and whispers, “Oh, if only I had a man as steady as you.” “You are what you love,” says the song playing in her house. Mr. Oak accepts this song as truth and imagines himself a human. Then he imagines the soul of a bonsai in her, but cannot bring himself to perform the bloody ritual of pulling it out of her. Finally a storm fells Mr. Oak at the same time her lover returns.

A rose bush, yew, blackberry bush, tulips, hazel, dandelions, owls, pigeons, and squirrels are all part of the story. And a rabbit. A blind rabbit gets caught in the rose bush and the roses delight in its torment by their thorns. Of course, the rabbit represents Mr. Oak and the roses represent love. The other plants of the backyard garden mock him and grow weary of his lovesick behavior. But the wise hazel tries to dissuade him. “You are a tree and she is a girl. And that is the way it must be.” Harmless, helpless, pitiful Mr. Oak is blinded to the unsolvability of his dilemma and therefore remains tormented by love. Probably the sound of the boyfriend’s car engine when he returns represents the sound of the approaching storm; a storm being natural and an engine being manmade.

There is a reference to a man and woman and one of Mr. Oak’s grandfathers. The grandfather in the story loved the woman in the story. This appears to be a reference to Adam and Eve and the Garden of Eden. Mr. Oak says the man in the story was the woman’s brother and that the grandfather protected them against the end of the world, though we all know Adam was Eve’s husband, not brother, and though we all know partaking of that tree brought disaster on them. The yew insists the tree in that story was an ash, not an oak. I suppose the word ash is symbolic of death, Adam and Eve’s spiritual death and Mr. Oak’s impending physical death. In cultural references, Adam and Eve’s misdeed with the tree is called The Fall. No doubt this corresponds to Mr. Oak’s physical fall. Mr. Oak’s version of that story reinforces his self inflicted denial about his relationship with the woman in the house. She is forbidden fruit, just as the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil was forbidden fruit.

So there is much symbolism to be explored here. Though it is a tragedy, it is delightfully written. The intro is, “Love fells the mightiest of us.” If my interpretation of the story is correct, Mr. Oak is a masterpiece. If you’re into fables, imagery, and symbolism, don’t miss this one.

“The Demon of Hochgarten” by Euan Harvey starts as a witchcraft story, turns into a murder mystery, then ends as a spiritual battle between the forces of good and evil. Someone has killed a baroness through witchcraft and a knight must discover who. He is not your garden variety knight, however. For one thing, he belongs to the Order of the Bloody Spear, which is sworn to investigate and fight witchcraft. For another, he is human on the outside and wolf on the inside, the wolf manifesting in times of battle or in urgent situations that require superhuman strength. The detective element is engaging. Otherwise, it’s a standard story. Pass on this one.

You can pass on “Melanie” by Aliette de Bodard as well.

The entire first section of the story is devoted to a discussion about who is good at math and who isn’t, who will pass the math exam and who won’t, who will get into a good school and who won’t, and whether the couple being observed will break up. The entire second section is taken up with a school dance and an apparent romantic rivalry. The entire third section is a discussion of the breakup of the above mentioned couple and the strange behavior of the math whiz member of the couple.

The story is filled with descriptions like, “He’s staring at the other students–all gorged with light: the light of numbers and curves, the endless dance of the formulas that rule the world,” “Numbers whirl beneath his white skin–numbers and equations, endlessly broken up, endlessly merging,” and “curves entwined with the rising and falling breath of the ocean, numbers woven out of the gulls’ screams and whispers of the wind…” We’re into the third section of the story before these descriptions start to make sense.

The fantasy element is revealed very late in the story and it’s worth the perseverance. But you will be tempted to give up before that point, anyway. So save yourself the time and pass on this story.

“The Unknown God,” by Ann Leckie, is not about a god, singular–the alleged existence of the supreme god. It’s about gods, plural. And faith and truth and purity. And atheism. And questions and answers. And curses. And love and rejection. And redemption. And religious fraud investigators. And drunkenness. Not a terribly interesting story. You can pass on this one too.

“How Interesting: a Tiny Man” by Harlan Ellison

“How Interesting: a Tiny Man” by Harlan Ellison

“Mister Oak” by Leah Bobet

“The Demon of Hochgarten” by Euan Harvey

“Mélanie” by Aliette de Bodard

“The Unknown God” by Ann Leckie

Reviewed by Nathan Goldman

Realms of Fantasy, a vibrantly illustrated, full-size fantasy magazine, offers in this issue a grab bag of fantasy themes, from the torment of a god to the love song of a tree. With stories from one expert and four relative unknowns, the writing is as diverse as the subject matter.

Harlan Ellison, an SF veteran extolled for the spine-tingling strangeness he so masterfully imbues in his pieces, opens the issue with “How Interesting: a Tiny Man.” Neither the concept (a scientist who develops sentient life) nor the theme (society’s repulsion against that which it fails to understand) is novel, but the narrative style – a simplistic first person account – is the polar opposite of overwrought Romance. This perspective transforms this story from a rehash of a tired archetype to a compelling and vital new exploration of human behavior. The unnamed narrator recounts in vague terms his time with the tiny man, digressing constantly and progressing gradually, as if choked up in nostalgia. Despite the vagueness, the reader comes to know and care for the narrator and his creation. This subtly radical story is exemplary of Ellison’s genius. He traces the human tendency to transform the intriguing into the monstrous, and it’s the highlight of the issue.

“Mister Oak” by Leah Bobet is a modern story wrapped up in fairy tale garb. It’s the tale of a tree painfully in love with a girl, and its struggle to attain her – or cope with its inability to do so. The dialogue is somewhat stilted, but in the context of a fable this is forgivable, and doesn’t detract from the reader’s enjoyment. It’s artfully written and lightly poetic, particularly Mister Oak’s fantasizing about his love metamorphosing into a tree, like a caterpillar undergoing chrysalis. Bobet has masterful rhythm that is hard to find in this genre: “He dreamed of it, slow dreams that move like the rings of trees. He tore her open to a perfect bonsai soul, and there was blood, blood.” Succinct and unique, this is not a story you’ll soon forget.

In “The Demon of Hochgarten,” Euan Harvey thrusts the reader into a theocratic world of swords and sorcery, where knights and demons abound. The protagonist, a Knight of the Bloody Spear named Stefan Von Stawy, arrives at a baron’s castle to solve the mystery of the baroness’ murder. It’s essentially a detective story, and, unfortunately, it falls prey to the clichés of both fantasy and mystery writing – flat characters, overwrought exposition and description, and an authorial voice that repeatedly reminds the reader that he is reading a story. The twist and resolution are clever, but that “Aha!” moment, where the detective finally connects the dots, is tired and forced. Overall the story feels like something you’ve already read and have little desire to read again.

Aliette de Bodard’s “Mélanie” appears to be modern fantasy, but the reader is never quite sure. For most of the story the speculative element is hidden beneath the surface – vague hints at some sort of magic driving Erwan’s visions of mathematical equations surging beneath the surface of the students’ flesh. But this could be just Bodard being poetic, and as a result the hints at magic seem forced or out of place, just an impediment to the reader’s appreciation of the fluid and well-executed language that describes these visions. Eventually, this otherwise mundane tale of a schoolboy’s fascination with a mysterious girl becomes a minor fantasy mystery. The middle is boring, but the ending is interesting. Still, the bits of this story that really shine are obscured by a stale concept and uncertainty of purpose.

The issue ends with “The Unknown God” by Ann Leckie. Aworo, one god in a world of many, does a stint as a human to consider if there exists some higher Truth, all the while worrying over his betrayal of a woman who turned him down. The story opens with a cluttered first sentence that, rather than draw the reader in, assaults him with minute details that could have been easily addressed later. The language’s clumsiness does not abate for some time. It’s most clearly evident in the description, which, like much fantasy writing, sounds like writing – it’s pure artifice, not something alive or natural. Overall, the story’s interesting concept is hard to understand because of the author’s limited sense of the power of words, from dull description to paragraph construction that makes it hard to understand who’s speaking when.

This issue of Realms of Fantasy is strongly front-loaded. It begins, wisely, with a great story by a seasoned veteran. But, by the halfway mark, the writing has become amateur. The product itself is highly appealing: each story is accompanied by a full-page, full-color image, and a host of other editorial material accompanies the stories. But when analyzed solely on the quality of its fiction, Realms of Fantasy falls short – at least for now.