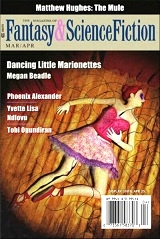

Fantasy & Science Fiction March/April 2022

Fantasy & Science Fiction March/April 2022

“Dancing Little Marionettes” by Megan Beadle

“The Mule” by Matthew Hughes

“Done in the Mire” by Adriana C. Grigore

“The Epic of Qu Shittu” by Tobi Ogundiran

“Void” by Rajeev Prasad

“These Brilliant Forms” by Phoenix Alexander

“From This Side of the Rock” by Yvette Lisa Ndlovu

“Lilith” by Ethan Smestad

“Makers of Chains” by Sarah A. Macklin

“Where God Grows Wild” by Frrank Oreto

“Woven” by Amanda Dier

“Nana” by Carl Walmsley

“Spirit to Spirit, Dust to Dust” by Anna Zumbro

“The Living Furniture” by Yefim Zozulya (trans. by Alex Shvartsman)

Reviewed by C.D. Lewis

From this year’s March/April issue of Fantasy & Science Fiction, Tangent reviews thirteen new works and one new translation of an early work from the Soviet Union. From classic-feeling high fantasy to weird fantasy to post-apocalyptic fantasy, there’s sure to be something for the fantasy reader. The review concludes with a plea for science fiction in future issues.

Megan Beadle’s “Dancing Little Marionettes” is a fantasy narrated by a craftsman and theater proprietor whose puppets can suffer workplace injuries and die. The plots depicted in the performances represent genuine drama causing true heartbreak to marionettes whose longings and romantic preferences are real. But maybe they can’t act: when a new couple takes over as the principal dancers, their lack of romantic spark makes for dull performances and business flags. The narrator cautions the reader against interpreting the story as a romance, though the story structure is Romance right down to the HEA. When the narrator says the original male lead “was not the villain” that too is a lie: between his absolutely unsympathetic “just get over it” response to the protagonist’s grief, his inflexible balled-fist posture when she does not comply, and his demand she resume life as the person she was before her sister died–-because that was more convenient for him because she was more cheerful and therefore easier to get along with–-it’s hard to imagine a more blatant caricature of a toxic ex. Yet the climax isn’t the feminist victory one sees when the protagonist outgrows the show to become an international star touring in the glitziest places possibly portrayed in purple prose. The climax occurs after, when a second male marionette woos her back to Prague where he’s built a theater for her and admits he made the mistake of his life letting her go, and they dance again and the reader understands that as older and wiser dolls they now possess the perspective to keep their love alive for a more mature happily-ever-after than they might have had as inexperienced youths. The reviewer enjoys romance plots and reads romance plots frequently when not reviewing short fiction. This work does execute the elements of a romance plot. However, it is so heavy-handed in painting its villains and fools that it’s hard to enjoy the journey. In particular, each named male character is depicted as devoid of personal insight, lying to himself to foster a delusion of control. But it’s a romance; she had to end up with one of them, didn’t she? At least one was allowed to develop some offscreen regret he didn’t properly worship the protagonist earlier. Sigh.

Matthew Hughes opens “The Mule” in an arcane institute where “a freelance discriminator” has been sponsored into a magical guild with an entertainingly longwinded name. “The Mule” follows and is set in the same world as “The Forlorn,” published in the September/October 2021 issue of F&SF, and it shares the same fantasy private investigator and the same entertaining language right down to the spell names that evoke Dungeons and Dragons (viz. Ochelga’s Immobilizing Relaxant). “The Mule” quickly establishes the guild as a magical community oversteeped in inflexible rules that must be resisted at some peril to accomplish anything worthwhile. The main character has little understanding what’s unfolding about him, so a reader can’t often tell whether he’s winning or losing. A combination of humor and ongoing surprise, rather than stakes or a protagonist’s goal, keeps pages turning; only when his safety is in jeopardy do we sense he’s got much in the way of a goal. Most of the action happens to the main character, rather than being conducted by him; in the climactic confrontation, he’s a spectator. “The Mule” makes able use of 13,000 words to provide a secondary-world high fantasy experience, complete with an entertaining array of obscure and archaic words for plain things.

Adriana C. Grigore’s “Done in the Mire” opens as a fantasy told in third-person close over the shoulder of a woman who stands at the bottom of a well looking up while talking to the stones of the well’s side. The main character’s goals are not immediately clear, and she seems at first to have no particular zeal to climb free, so readers who expect the story structures typically appearing in genre fiction (scene goals failing due to setbacks that cause goal evolution until the whole resolves in a climax) may be disappointed. Ignorance of the main character’s goal, or even her values, works against understanding why she does what she does and why it should matter; without a description of the stakes, it’s not clear what consequence might follow failure. A few thousand words in, one understands that the malign spirit guardian of a treasure has cursed the main character to dwell in the bottom of an island’s well, where she has persisted undying while feasting on the corpses of treasure-hunters who’ve fallen or been thrown in. For a vignette establishing a setting and how the curse works, thousands of words feels really long. The curse trapping the main character is eventually resolved by an interloper, who appears halfway into the story, collects intelligence from the main character, negotiates off-screen to resolve the curse and free the main character, and creates the only excitement in the story by announcing a deadline for a task required to win them both free; they then accomplish the goal without opposition. The story’s conclusion seems designed to give the reader a warm feeling that loneliness comes to an end and freedom is at hand, which the reviewer admits both feel quite good. But it’s so much better when these feel earned. Since the main character doesn’t actually solve the problem, one might be tempted to call the newcomer the protagonist; she does, after all, rescue the trapped woman with a classic solution of culture-hero cleverness, negotiating. The fact we hear about this happening off-screen after it happens dampens its thrill. The reviewer feels the story of the newcomer would be really exciting to read: compelled to work on a ship headed to find a lost treasure, she survives the slaughter of all her crewmates on a haunted island where she negotiates her way past two cursed guardians to win her freedom and make an ally needed to escape the island. Awesome! But this is not the story shown readers. Hearing about this from the viewpoint of a character who finds herself surprised to be freed from captivity lacks the excitement seemingly so close at hand in the story of the woman who rescues her.

Tobi Ogundiran’s fantasy “The Epic of Qu Shittu” opens on a stowaway sneaking into the ship’s hold of a deadly enchanter in the hope of meeting the legend himself. What could possibly go wrong? Ogundiran’s language makes it a pleasure to read room descriptions; horror and humor meet in descriptions of “skulls wearing identical smiles as if sharing some secret joke.” As the story builds, the reader discovers the joke’s a dark one: the cost of becoming a powerful enchanter is as awful as the pressures that drove him—or worse. The story-within-a-story structure affords the reader two protagonists, the stowaway and the enchanter, and the story elements laid before the reader support so many directions it’s not initially clear whether “The Epic of Qu Shittu” will turn out to be a tragedy, a heist, a revenge plot, or something else; it’s an exciting read that adds psychological elements and moral problems to the physical conflicts. The dark ending suits the characters.

Rajeev Prasad’s “Void” opens in a satellite orbiting Mars in a palliative care ward that uses its own airlock to dump human corpses into space (the titular “Void”). This review is long, because the reviewer feels some explanation is needed for a negative review, but for readers uninterested in the details the worst problem is that the happy ending presented by “Void” and accepted as a positive outcome by the main characters requires them all to perceive success when one of their number transfers to Earth where he won’t be asked to murder any space patients in his care, despite that (a) the murder policy and the nonsensical corpse disposal program will continue, (b) the remaining physician will presumably continue to be ordered to murder and space patients, because they haven’t stopped the policy, and (c) all the characters know they have only resolved at best some personal inconvenience but that not a thing has been done to stop the problem underlying the entire story. A secondary problem is bad enough that the reviewer would not have finished the story had a review not been promised, and that is that either more work should have been done to make story details believable in a universe where physics and economics are expected to govern the behavior of physical objects and the behavior of governments, or “Void” should be given a setting that suggests fantasy rather than science fiction, because the expectation of science fiction proved deeply jarring. “Void” does not resolve a medical ethics problem or provide a science fiction plot, and as unpleasant as it is the reviewer does not choose to characterize it further.

The setting teases a science fiction story, but “Void” disappoints the expectation of reading science fiction. Setting science fiction off-world is common enough that the genre has established tropes and expectations, including the scarcity of resources in orbit or in deep space, and the extent to which such resources are carefully shepherded by those struggling to survive off-world privations (“The Cold Equations”, Dune, The Moon is a Harsh Mistress, The Mote in God’s Eye, etc.). One need not make offworld settings places of scarcity, but abundance in the vacuum of space is so peculiar as to require explanation for deliberate waste if only to provide sufficient explanation to help experienced science fiction readers fund plausible the setting when exposed to such an element. A well-known example is Star Trek in which the answers to the utopic lack of privation in deep space are (a) replicators coupled with unlimited power from dilithium reactors, and/or (b) this scene is set on a holodeck. Wasting resources like organic matter in orbit or on Mars represents a serious distraction to readers who have been repeatedly told how valuable everything is in a place with nothing. In the same vein, why would trauma victims on Mars be launched into orbit for treatment, much less for triage? That’s a lot of energy to invest in something more easily done on the surface, where people live and work and therefore presumably have a workplace infirmary (and if not, why?). Based on the story problem eventually revealed, “Void” could as easily be set on a planet. Without investing in worldbuilding to explain the shocking behavior depicted, the setting in orbit was a mistake.

But it’s set in Martian orbit, which brings one back to the corpses. A science-fiction explanation for the handling of human remains might be grounded in religion or ecology or frankly anything–-but some grounding would support the depicted behavior, and in an SF story the basis for the practice would be consistent with facts provided to the reader. Readers of current news, aware of the real-world catastrophe of space junk cluttering valuable high-use Earth orbits, will probably react with greater alarm than mere SF enthusiasts. In what universe would a formal policy require personnel in orbit to expel into space, over and over, human-sized objects where something big enough to destroy a spacecraft would inevitably add forever to the hazards facing all future personnel and craft in the orbit? This practice isn’t introduced so a hero protagonist can halt the madness, but rather, is presented as though the reader should accept it just like everyone in the story accepts it. Ignoring for the moment the story’s evil plot to kill unwilling patients, the dangerous plan to mine a valuable orbit with human corpses is hard to believe would be accepted during the happy ending by everyone on the station who knows about the palliative care airlock and the songs the main character sings while ejecting corpses from it. Yet the whole station seems designed with the awful policy in mind: an airlock to the void is situated right in the palliative care wing. The more elements that a reader can’t believe, the harder it is to get investment in the story the author hopes to tell. This reader would have quit over the unbelievable world long before discovering the plot problems.

“Void” centers on a pair of physicians. When a story depicts a physician ordered to kill a helpless patient, one expects some kind of resolution: a protagonist, for example, might be expected to object to the orders and either put an end to them, or be destroyed opposing them. A physician who agrees to kill unwilling patients would be expected to have a solid basis for conduct so offensive as betraying the healing professions with an act of murder (the killings at issue in “Void” have motives that are expedient or political rather than representing action at the request, or for the benefit, of a patient). The conflict in “Void” appears to arise from the fact that although the physicians both intend to commit the murders, they also feel a little bad inside. But, crucially, not bad enough to object: they discuss it and are pleased to find each agrees to do it anyway, then plan how to hide it from observers. Their discomfort is exacerbated and prolonged by a station outsider who, being a better healer, begins to cure some injured whom the protagonists have been ordered to kill and space. If the story were re-skinned as a fantasy, this character could be written as a witch, elf, or wizard; in historic fiction, the outsider could have access to treatment techniques superior to those commonly available in the area. A historic example of this is Dr. James Barry (actually Margaret Ann Bulkley passing as a man to study medicine and become an Army surgeon) who was an early champion of sanitation and the first person documented to perform a successful Caesarian delivery on the continent of Africa. Nothing in the explanation how an outsider heals people in “Void” affects the plot, however, much less turns “Void” into SF.

A proper story climax serves as the crucible that proves who the character really is, forcing the character to a hard choice that enables the reader to see who the character is–-or becomes. By rescuing characters from a climactic choice, “Void” feels less like it’s making an argument through the example of a heroic (or tragic) protagonist, and more like it’s proselytizing for a church of unexpectedly shallow and self-interested parishioners. Instead of a climactic last-minute conflict among the protagonists or within one, or a climax in which the protagonists confront the visiting healer, “Void” avoids presenting any character a climactic decision: the one physician actually present for the climax is knocked out during a patient’s escape so he’s protected from making hard choices. Unlike early Grisham novels that depict victorious protagonist lawyers’ happily-ever-after as including a decision to leave the practice of law, “Void” spares its protagonist even making the decision to quit: he doesn’t decide an on-screen climax to change his life, or even to reject his evil orders. The crucial moment occurs off-screen when his superiors gift the unconscious protagonist a trip back to Earth for treatment. This isn’t a story about a human forced to confront and solve an external problem or an internal problem, much less (as one likes to see) both. Instead “Void” displays its outwitted main characters deciding in their hearts to abandon a made-to-be-rejected policy to hide from patients and their families exactly how and why patients were dying without anyone ordering definitive treatment (i.e., due to secretly-ordered killings and disposal into the void of space). As outrageous as the orders are, the protagonists not only don’t stop the orders, they don’t even try. The happy ending leaves the murder policy in place (and the unbelievable silly space corpse dumping, too). The knocked-out protagonist is saved from carrying out evil orders first by being defeated in a purely physical contest, then by a medical transfer that results in the evil policy continuing while the protagonist is spared the burden of carrying it out himself. “Void” isn’t a drama on medical ethics because nobody is forced to confront an issue of medical ethics: they’re allowed to escape the choice without ever confronting the evil policy, which they leave operating without objection. This reminds the reviewer of the decision to free Dobby in Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets but leave all other house-elves in slavery through the next five (five!) books (and apparently forever after) despite granting competent protagonists government jobs enforcing wizard law. “Void” appears to expect the reader to rejoice to see characters relieved from having to do murders personally, even while they do nothing to stop it. It’s harder to imagine a more self-centered conclusion than “Thank goodness now you can now do all those awful murders for me! That was the worst!” The story presents this resolution like it’s solved something; even the competent healer from off-station looks on in happy approval. The victory is an illusion for the self-absorbed and the climactic decision is stolen from the protagonist.

More could be said about the transparency and believability of characters’ motivations and decisions, but a review ought not be longer than the work. The reviewer will draw this to a close: the awful conclusion shows the story isn’t about ethics but personal convenience. The piece sends a terrible message that teaches nothing about humans learning to solve problems, the triumph of humanity over oppression, or the benefits of critical thinking. The only enjoyment “Void” seems to offer is the “we won!” thrill for readers whose biases align with the end-state of the waffling protagonist, provided those readers overlook that the “protagonist” has rescued nobody, even himself, and leaves the orbital station as broken as he found it. The main characters feel better, but they haven’t stopped the policy of secrecy, lies, killing, and spacing corpses. “Void” solves no problem except the personal discomfort of a physician willing to murder his own patients, who for no particularly persuasive reason changes his mind about one or two individual victims. It’s a victory for those fooled into the conviction the world’s problems are only about themselves, and that escaping villains is therefore just as much a win as halting a villain’s campaign of terror. Those looking for a story that treats a medical ethics problem with the weight it merits must look elsewhere and those expecting a science fiction story face disappointment.

Phoenix Alexander sets the short story “These Brilliant Forms” on a spacecraft with a small crew that includes individuals who dismiss part of their own number as members of their in-group, and treat them as “other” even while they remain together. “These Brilliant Forms” dwells on social contrasts: togetherness and aloneness; belonging and exclusion; humanity and alien-ness. It’s uncomfortable and melancholy–-excellent feelings from which to approach or experience these topics. Many science fiction stories contain one impossible element, even if it is only faster-than-light travel, and a convention seems widely accepted to overlook one fantastic feature of an SF universe. “These Brilliant Forms” introduces a character physically adapted to survival in hard vacuum and the ability to move and maneuver without propellants through vacuum in zero-G using a technique that suggests mind power or a perpetual motion process, but it is unusual and suited to the character and might not upset the work’s SF flavor in the same way that, for example, The Force transforms Star Wars into a fantasy. On the other hand, the character does refer to some of his own activities as a “spell” and some others call him a “witch.” Whether it’s science fiction doesn’t impact its quality, but the reviewer likes to identify genre to readers and this one seems to have taken some effort to vote itself a fantasy. The ship-less spacefarer character has two effects on the story: first, his visual distinctness and inability to hear and his need for accommodation to communicate with the rest of the crew fuel the story’s first example of the crew “other”-ing one of their own, as some aboard regard him at least occasionally as an outsider and subhuman; and second, he establishes that the story universe has thinking beings with unexpected physical appearances and the ability to live in space without spacecraft. The treatment of this character as an other by his peers introduces a series of similar assignments of characters to out-groups by other characters: an onlooker to a pair of lovers feels like an outsider, experienced spacefarers feel distinct and different from those with stable, predictable, planetside occupations, and so on. The ship itself travels into a distant backwater where its whole crew is alone and beyond help. Everybody seems at risk of being treated like an alien. The protagonist’s climactic decision at once proves he’s a better person than some of his judgmental crewmates, and drives them to regard him as a member even as they lose him forever. Unlike Erin Barbeau’s “Ice Fishing on Europa” this story of difference and other-ness isn’t so much a happy conclusion that even the truly miserable are not alone, so much as it is a tragedy that differences really do prevent people from achieving lasting enjoyment within their community.

Yvette Lisa Ndlovu’s “From This Side of the Rock” presents a fantasy horror story about surrendering identity to reduce the pain of nonconformity under an authoritarian government. The vibe reminds the reviewer of ‘80s fiction written to horrify Americans with loss of individuality to Soviet indoctrination, particularly in post-invasion occupied-America contexts. “From This Side of the Rock” makes the evil less about the crushing of individuality and more about the loss of identity: a prospective citizen about to naturalize looks forward to no longer being a “kwerekwere” (search engines explain this term is used in some African countries to denigrate undesirable dark-skinned foreigners), and imagines being allowed to open an art studio after naturalizing. Those who conduct naturalization ceremonies aren’t, as in the Soviet indoctrination horrors, primarily interested in forming compliant sheep to carry out the labor required by a local five-year plan; instead, “From This Side of the Rock” depicts “naturalization priests” who regard immigrants as vermin and deliberately humiliate and dehumanize them as the price of naturalization. There’s no subtlety: as in the Soviet propaganda horror, conformity crushes individuality and renders victims powerless. Here, however, it’s not a con to enhance collective productivity but a personal attack on the dignity and identity of the individual: from an artist, eyes are stolen. It’s a personal attack with no profit motive; it’s about power only, reminiscent of statutes that criminalize the marriage you want or the decision not to give birth to a rapist’s infant. Instead of protesting Soviet conformity “From This Side of the Rock” protests the world bigots would impose, crushing foreigners’ pride in what makes them themselves.

Ethan Smestad opens “Lilith” on a Mars undergoing terraforming. The setting raises hopes of a science fiction story, but medically nonsensical elements regarding cancer therapy raise a concern the work is more grounded in faith than science. Likewise, when one of the characters expresses the belief humanity can be saved on Mars if the two people on the planet are able to reproduce, it’s clear to readers with any exposure to the subject that the proposition is contrary to established understanding and the research into species with historic gene pool bottlenecks–a situation that could be remedied with a solution drawn from existing reproductive or genetic technologies, which “Lilith” doesn’t bother to provide. Since the titular character’s climactic reveal is grounded in an analogy drawn from her fantasy cancer therapy, which dashes a character’s uneducated expectations involving the rescue of the human species from a single mating pair, a person with any background in medicine or genetics will find the reveal’s force is overwhelmed by irritation at the multiple levels of nonsense involved in the protagonist’s scheme. Those who know too little about medicine or genetics to be irritated to see them both misrepresented in a modern story might enjoy the work better, but the protagonist’s victory isn’t for everyone: “Lilith” is a dark fantasy whose conclusion argues the world is better off without any people in it. The misanthropic vibe is amplified by the male character’s evolution from an oblivious fool to a disappointed idiot, capped by an ignominious fate, in case that is your bag.

Sarah A. Macklin opens the post-apocalyptic fantasy “Maker of Chains” outside the protagonist’s ruined jewelry shop. “Maker of Chains” quickly establishes the protagonist’s mission. Once underway, Macklin masterfully portrays a grim-future fantasy wasteland. Magic isn’t portrayed like the output from a mystic vending machine but more interestingly: a risky and challenging enterprise that imperils the user’s very identity. This leads directly to the story’s climax, which isn’t a dragon-slaying thrill ride but a struggle to protect a person who started out trying to protect themselves in a dangerous world and lost himself in a self-destructive cycle of amassing power after forgetting its purpose. Some monsters, it seems, are just people who got lost. Excellent setup.

Frank Oreto’s sets the short fantasy “Where God Grows Wild” in a world in which reproduction–-human and animal–-is connected to plant growth, desire is interlinked with pollen, and a church that claims authority derived from a plant-goddess decides who has earned the right to children. Social obligations, garden plots, land boundaries, and family relations all take on new meaning in this weird world. As intermingled as these things all are, descriptions impart a kind of synesthesia in which lust and religion and farming and rotting flesh all seem to embrace further meaning. It’s an adventure: girl meets boy, girl commits heresy to save maybe-completely-unrelated-brother and evades death by ecstatic participants in a religious suicide rite, boy proposes to girl, et cetera. You’ve never read the like. Recommended.

Amanda Dier’s “Woven” depicts a child whose mother’s stories about Others left him more interested in than hateful of faeries, which gets him into trouble with the judgmental and closed-minded grandmother who’s been left to raise him. The story’s structure isn’t a modern genre plot arc that leads to a climactic decision that proves the protagonist is a hero, but recalls the older virtuous-protagonist-rewarded structure found in fables and fairy tales. Yet the reward isn’t bestowed without apparent cause as if by divine decree as occurs in the Grimm-collected “The Girl Without Hands”: after the protagonist of “Woven” carefully protects a fairy in danger, that very fairy rescues the boy when he himself comes under threat. “Woven” doesn’t invest word count in fairy lore, but favors and scale-balancing are certainly solid elements with which to close a story about the Fae. “Woven” delivers this while building villains out of narrow-minded people too busy with their own problems to really look at the world to think deeply about it, and uncritically accept that they should attack things different and “other” wherever they find it. The climactic solution suggests we’re more interconnected with the Other than some of us may realize.

Carl Walmsley’s “Nana” offers a short story in which one can buy simulations of deceased loved ones. But what does a strained marriage need more than an immortal mother-in-law whose susceptibility to being made to vanish on a command is by itself a new reason to fight? The female lead dismisses her husband’s attempt to talk through problems, and prefers to move forward in the firm grip of denial: things must go the right way because they have to. Instead of representing an exciting new adversary, the simulated Nana serves to provoke nostalgia while convincing onlookers the loss is real. The seductive power of willful denial and the agony of losing loved ones will resonate with a lot of readers, and the twist ending will stab anyone who’s connected emotionally with the characters.

Anna Zumbro sets the dark fantasy “Spirit to Spirit, Dust to Dust” in a parched farming community where one might imagine wielding power over water would represent a great boon. But power isn’t free, and trying to make a return on a magic bargain seems to involve ugly restocking fees. Fans of dark fantasy, who want to see happy endings crushed and composted, will enjoy the piece’s dismal setting and embrace its almost-joy collapsing into disaster.

Yefim Zozulya’s “The Living Furniture” is Soviet-era dystopic fantasy translated into English by Alex Shvartsman. In it, the wealthy Master Ikaj employs human beings as tools not in a figurative sense, but to serve as wheel spokes, chair backs, wallpaper, bed legs, etc. Master Ikaj sits in a study that is a “technological miracle” personally “designed by a famous American engineer” and which required “several years to build” and included “[t]hree thousand human faces [to] ma[k]e up the wallpaper” while “their bodies remained invisible.” Without the aid of history, one might imagine this description an anti-Western smear intended to suggest Stalinist Russia as a preferred alternative; however, Zozulya’s corpus is full of criticism of Soviet methods, so the anti-American description may have been a stratagem to get an anti-establishment story past censors. Indeed, the final line of the story invites “a better” story on the topic, presumably one free from censorship. Publishing a translation of a story so influenced by Soviet oppressions seems particularly timely while Russia’s newest dictator seeks to repair “the greatest geopolitical tragedy of the twentieth century” (the collapse of the Soviet empire) by ordering Russian youths “into a wood chipper” where they are expected to crush a democratically elected government and impose a puppet dictatorship. The original story was published in the Soviet Union after the revolution against the Tsar had been hijacked by Stalin, who also spent human lives like cheap coin whenever expedient, including through genocide against Soviet-occupied Ukraine by exporting their wheat while Ukrainians starved. Zozulya’s uses the dialogue of a worker-slave to deliver his argument against tyranny. Given the censorship in effect at the time of publication, it’s not surprising its climax occurs offscreen. This would feel like a problem in a new work, but in a work that is both the product of an oppressive regime of censorship, and a translation published while the old oppressor’s successors seek to restore their lost empire atop their peaceful neighbors, the story’s missing climax and its call for action serve to direct attention to the fact the future is still in the hands of the living. The reviewer recommends this work not so much as a story but as an important historical artifact that draws attention to problems that threaten human beings still living under autocratic rule more than a century after receiving the wonderful news they’d successfully deposed their Tzar. The news Russians had a new dictator might have been forbidden from print, but it was no secret.

Lastly, a word on science fiction. The reviewer accepts and appreciates futuristic or post-apocalyptic settings for stories by those who don’t choose to tell science fiction stories. There’s nothing wrong with writing a fantasy with a futuristic skin (like Star Wars, set in a universe in which key characters use faith-based magic) or a drama set in space or other worlds (such as any space western, such as most episodes of Firefly). Science fiction must turn on some technology or natural principle (even a made-up one). This doesn’t mean the story isn’t about characters–even truly hard science fiction like “The Cold Equations” wouldn’t matter to anyone if Tom Godwin hadn’t invested word count building concern for the characters and their relationships–but to be science fiction the story problem must involve humans acting in a cause-and-effect world governed by knowable natural laws that influence the results of characters’ actions for good or ill. A political drama on a space station that would be no different if set in a historic castle isn’t science fiction. I would hope that future issues of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction could once again include science fiction. It’s good to see fantasy and science fiction.

C.D. Lewis lives and writes in Faerie.