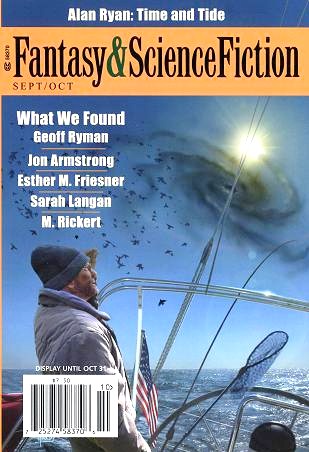

Fantasy and Science Fiction, September/October 2011

Fantasy and Science Fiction, September/October 2011

“Rutger and Baby Do Jotenheim” by Esther M. Friesner

“A Borrowed Heart” by Deborah J. Ross

“Anise” by Chris DeVito

“Where Have All the Young Men Gone?” by Albert E. Cowdrey

“What We Found” by Geoff Ryman

“The Man Inside Black Betty” by Sarah Langan

“Bright Moment” by Daniel Marcus

“The Corpse Painter’s Masterpiece” by M. Rickert

“Aisle 1047” by Jon Armstrong

“Spider Hill” by Donald Mead

“Overtaken” by Karl Bunker

“Time and Tide” by Alan Peter Ryan

Reviewed by Colleen Chen

The issue begins with Esther M. Friesner’s “Rutger and Baby do Jotenheim,” a lighthearted fantasy romp through Norse myth and some of the sillier aspects of American culture. Rutger, “a substitute adjunct professor of Comparative Mythology and Folklore at one of our nation’s finest online colleges,” and Baby, his ex-stripper ladylove, run out of gas in backwoods Minnesota. They get lost in the woods and run into a bunch of giants from Norse lore, and Rutger realizes that they’ve walked into a replaying of a myth in which the giants challenge Thor and his companions to trials to prove their worth. Through the events that follow, Rutger realizes that Baby has more to her than just being a pretty pole-dancing pasties-wearing champion with a poodle in her purse and plastic parts.

This is one of the stories that had me laughing out loud. The characters are all people who would irritate me in real life, but Friesner’s treatment of their exploits makes me want to cheer them on, and perhaps toast them with a tankard of ale the size of my refrigerator. A fun read.

Deborah Ross’ “A Borrowed Heart” is a period piece occurring in a world where vampires and demonic entities endanger the daily lives of people such as Lenore, a high-class prostitute. In her line of work she encounters a succubus; instead of giving this murdering female demon-spirit the death she deserves, Lenore shows her kindness. To thank Lenore, the succubus gives her one of the many hearts she has accumulated, in the form of a ruby on a chain.

Lenore thinks this borrowed heart might be a key to remedying a more personal situation—her sister is sick with a broken heart and her father, who threw Lenore out, asks her to return. Lenore’s solution is unexpected as she learns more about what it takes to heal the ones she loves.

This story has elements of soft horror but reminded me a lot of a period romance, except the main character doesn’t get a romance. Since I’m a big fan of period romances, and I’m conditioned to expect delivery on the formulas, I was a bit disappointed by the slightly anti-climactic, albeit non-formulaic, ending. I think for me, this story would work better within the context of a novel, to give more space for these fascinating characters to play. Lenore is a remarkable and likeable heroine and I think she deserves much more page time.

Chris DeVito’s “Anise” is set in the future in a time when death no longer stops people from living. Anise is an angst-ridden woman whose relationship with her husband has become strained ever since he died and was reconstructed into a “breather,” needing to plug into a machine every day to exchange fluids and keep things running properly. For support, she turns to a co-worker at the fetus factory, and she also starts asking for advice from the artificial intelligence who runs the tanks. As she questions concepts of life and death, consciousness, love, freedom, and control, she begins to discover that her alienation from her husband might not be just because he’s dead.

This is my favorite story of the issue. From the first line, it’s compelling and raw, with an edge of tension that builds in a way that I struggled between wanting to skim to find out if everything would be all right, and wanting to slow down to enjoy the clever, often funny prose. The story gets to deep questions quickly and without any intellectual snobbery, leaving the reader to choose her own depth of being provoked to think versus being purely entertained.

Albert E. Cowdrey’s “Where Have All the Young Men Gone?” tells the story of Henry, a military historian and academic, whose fascination with the military museum in Gmundt, Austria, leads him into the thick of the legend of the Milkmaid—a vengeful ghost who died in the barracks where the museum was constructed. In agreeing to investigate the disappearance of a young man, Henry witnesses something inexplicable and supernatural, along with having to confront his own personal demons regarding death and the desire to live.

I would label this piece as a ghost story, or a mystery with elements of horror. It’s a compelling read, suspenseful and chilling, and I especially appreciated how skillfully the Austrian setting was presented. Personally I didn’t like the ending, but it will satisfy those who favor the poetically just.

Geoff Ryman’s “What We Found” takes place in modern-day or a slightly futuristic Makurdi, Nigeria. It is a rich, deeply layered tale with an interweaving of folklore and science, consciousness and fact. On the brink of marriage, Patrick is petrified of “passing on the poison” of bad character through genes. He has plenty of unappealing examples—his father and brother were crazy, his grandmother a kleptomaniac. This fear is grounded in a folk belief that the grandson first born after the grandfather’s death will continue the latter’s life, and Patrick’s own scientific experiments connecting inherited traits to stress levels support this concept. We see how Patrick deals with his fear as the story moves seamlessly from present to past and back.

I thought this was the most “literary” story of this issue. Readers in the mood for something more thought-provoking and less pure entertainment might enjoy this complicated jewel of a story, where different angles bring out different facets, light and dark.

“The Man Inside Black Betty: Is Nicholas Wellington the World’s Best Last Hope?” written by Saurub Ramesh, with research by Sarah Langan, tells of a near-future scenario in which a black hole, “Black Betty,” is growing over New York as more matter gets sucked into it. Nicholas Wellington, the world’s foremost expert on black holes, warns that soon the point of no return will pass and it’ll be too late to save the Earth from eventually getting consumed by Black Betty. The story is less about the impending disaster as about why no one will heed Wellington’s advice—he’s a modern Cassandra, tragic and unlikeable, in a position of power yet disempowered by his own spotty past and alienating personality.

In the face of the extinction of all life, Wellington tries to save birds hit by Black Betty’s radiation, reflecting the futility of the hope that people will emerge from the denial that has relegated Black Betty to the background of their lives.

I found this story really depressing, even more so because it’s done so convincingly that it makes this scenario seem entirely possible as our future. Not only is the science here excellent, but the story is reflective of modern-day politics and its tendency to argue over personality and minutiae even as the world falls apart about its ears. Bleak and realistic—a good story, but definitely not upbeat.

Daniel Marcus’ “Bright Moment” begins with Arun surfing on the waves of a distant planet that is reached through a wormhole and marked for terraforming. His glimpse of a giant squidlike life-form distracts him, and he suffers an accident. During his recovery, he learns that the small network of souls to which he’s connected through the aether, his “pod,” is divorcing him. Thus, he faces moral conflict alone when he sees how corporate greed deals with his discovery of the first intelligent extraterrestrials his people have found.

This is another story that I thought would do well if it took place within the context of a novel. The world built is complex, with many fascinating aspects, and the descriptions here are just lovely. This brief look at Arun’s universe is a sad and beautiful one. A classic science fiction tale, done well.

M. Rickert’s “The Corpse Painter’s Masterpiece” is a psychological, almost surreal tale of grief and death, with a supernatural element. The corpse painter lives in isolation, his most frequent visitor the sheriff, who brings him corpses to beautify for their funerals. The story has two twists: first, the sheriff brings the dead father of the painter to be painted. The second is that we learn of the sheriff’s personal tragedy—the death of his young son—and how he and his wife have dealt, or not dealt, with it. The corpse painter and the sheriff play roles in each other’s growth around these elements of creation and destruction, light and darkness.

You wouldn’t think of this as being a feel-good story at all, but the end, for me, makes the rest of the story simply a poetic setup for a culminating image so beautiful it made me cry both times I read it. In fact even as I think about it I feel like reading it again, just for that.

Jon Armstrong’s “Aisle 1047” tells the futuristic story of a young saleswoman’s trial by fire through the vicissitudes of retail sales competition, and how it leads her to question her very identity and purpose. Tiffan3, a soft-hearted, obliging saleswarrior who was trained in the subtle “poetry of fashion commerce” discovers through a slide in sales points to a cruder brand that her poetic WarTalk no longer beats the competition. When her manager wants to fire her and relaunch the brand with a haute sales war much dirtier than what Tiffan3 is used to, Tiffan3 demands to lead the war. After her fashion martial arts training, she is dogged by an existential angst over what her Brand truly is—the one that chose her, or should she aspire to dream of her own brand? As she returns to face the new challenges of a retail world turned ugly, she makes her commitment and finds a new sense of self in doing so.

This is a colorful and enjoyable piece. It takes some close reading because there’s so many made-up words, but it’s worth it. It seems particularly relevant in a time when people are having to have jobs choose them, rather than choosing jobs; Tiffan3’s journey to find herself showed her that she wasn’t her job; she was her act of committing to a job. There are many levels of depth within a wonderful and highly creative story.

Donald Mead’s “Spider Hill” is a funny, lighthearted coming-of-age story about 17-year-old Gina, who for thirteen years has cast a Halloween spell with her grandmother on a pumpkin patch on Spider Hill. They carve the pumpkins and dance naked on the hill to bring men who’d died there 40 years ago back to shine their soul-lights from the pumpkins. This year, Gina discovers that there’s a sinister side to what she’s been doing, which pushes her to find her own power alongside the witchcraft that runs in her family.

Gina is a great character, and I loved her interactions particularly with Egan, a boy who has a crush on her. I don’t want to give too much away, but the sex scene is hilarious. An easy, fun read.

[Please note that the following review contains a spoiler alert.–ed.]

Karl Bunker’s “Overtaken” is introduced as a fable in the tradition of works from the Golden Age of science fiction. The Aotea is a ship that left Earth 378 years ago; its crew remains asleep throughout the tale, and a conversation occurs between Aotea’s artificial intelligence and the Rejoindre, sent to overtake and rescue the humans aboard. Rejoindre wants to take the humans back to Earth and help them transcend, to reintegrate them with a planet where humanity is now “free”—where want, death, and suffering no longer exist, nor do any limitations of the flesh. Aotea responds by telling a story, the response to which will determine its actions.

The story Aotea’s AI told made me cry. That and the rest of the story is effective as a fable about the value of the flesh’s limitations. However—and here’s a spoiler alert—what didn’t work for me so much was Aotea blasting Rejoindre to nothing right after telling a tale of human worth. Because even if humanity no longer suffers, it just doesn’t seem appropriate to me for a life-respecting AI to kill ships that are basically humans in another form.

Alan Peter Ryan’s “Time and Tide” is the chilling story of Frank, a teenaged boy who is haunted, psychologically and perhaps literally, by the drowned family favorite, Junior. Before Frank can escape the memories by going to college in a state far from the ocean, he finds that the old wardrobe in Junior’s room, which his father wants to move to his room, forces him to confront the horror again.

This story would be perfect for a Twilight Zone episode; it begins with a creepy note and gets progressively more so. Frank’s colorlessness doesn’t make him an appealing character, but his rather hollow, unformed state, his passivity, are very real. The final moments of this story are as disturbing as they are memorable.