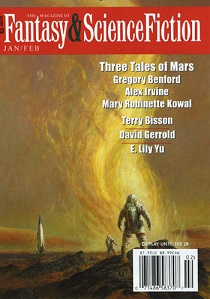

Fantasy & Science Fiction, January/February 2016

Fantasy & Science Fiction, January/February 2016

“Vortex” by Gregory Benford

Reviewed by Nicky Magas

After their first great discovery of strange microbial life on Mars (The Martian Race–1999), Julia and Viktor are not only minor celebrities back on Earth, but leading experts on the life form dubbed ‘Marsmat.’ Not that expert means they know everything about the semi-intelligent sheets of life under the Martian surface, only that they know more than anyone else who has come after them. So when a group of Chinese researchers start having trouble with the section of Marsmat they are studying in Gregory Benford’s “Vortex,” Julia and Viktor are called in to give advice based on what little they know. But with war and political trouble on Earth affecting their communications, tensions run high and only add to the rapidly growing problems on the red planet.

“Vortex” goes big with the science in showcasing what a potential Martian life form might look like, and how it might respond to human interaction. In speculating what earlier scientific colonization of Mars might look like, Benford introduces political intrigue, and heavy mistrust that disrupts efforts to study the Marsmat. The ethical question of whether or not humanity even should tinker with an extra-terrestrial life form lingers in the background as the Marsmat continues to express distress. As a sequel to the story of the original discovery of the Marsmat, “Vortex” shows the consequences of humans mucking about where they are not wanted.

Geo-political crises on Earth have caused the discontinuation of all manned missions past lunar orbit in Alex Irvine’s “Number Nine Moon.” But for three inhabitants of Mars, the sudden evacuation of the colonies means a whole lot of empty compounds full of interesting things to discover—and pilfer. But their foray into illegal exploration ends in disaster immediately after touching down when a sinkhole swallows their rover and one of their crew. With just Stueby and Bridget left and a clock ticking down on an evacuation rendezvous, the pair have only their limited experience and whatever is left to be salvaged from the Hellas Basin colony to get them home. And Mars is very, very good at killing people.

“Number Nine Moon” opens very quickly with a traumatic event that eats away at the characters’ psyche and composure throughout the rest of the story. Frantic, clipped and at times erratic thoughts and dialogue within and between Steuby and Bridget give the tone of “Number Nine Moon” the feeling of being stretched to the breaking point. Unfortunately, the pacing is a bit unbalanced with long periods of waiting in between flourishes of activity. “Number Nine Moon” is nonetheless an exciting Mars escape story full of thrills and close calls that will have readers on the edge of their seats in expectation for the next disaster to befall the unlucky protagonists.

Helena would like nothing more than to make her girlfriend smile in Bennett North’s “Smooth Stones and Empty Bones.” Unfortunately, Mariposa has little to smile about these days. Her little brother Jovi has gone missing without a trace, and with each day that passes it’s becoming increasingly likely that the boy has died. But Helena has a secret. That her mother is a witch is common—and reviled—knowledge, but they have in their possession a set of peculiar stones with the power to revive the dead. If they can find Jovi, if he hasn’t been dead too long, it’s possible that Mariposa just might smile after all.

“Smooth Stones and Empty Bones” shines brightest at the end. The tension dials up to eleven and the reader feels a real flutter of anxiety for Helena. Before that point, however, the story meanders within Helena and Mariposa’s relationship, which is itself difficult to find believable, given the characters of both young women. North crafts some lovely whimsical imagery around death and dying, and while the ending does sneak up on readers, it nonetheless has a powerful message.

Sometimes when people die they leave, but other times they stay right where they are. In “The White Piano” by David Gerrold, some ghosts stick around to share a cherished memory with the living. When the protagonist’s mother falls ill and dies, he and his sister are sent to live with their grandmother. Grief and loneliness combine to make the young boy imagine a ghostly specter at night. Convinced his mother’s ghost is angry at him he runs distraught to his grandmother who, with a touching story, helps the boy understand the nature of ghosts, grief, and the power of music.

Gerrold tells a fantastically well-put together story in “The White Piano.” It opens with a frame story that is so long and so compelling the reader could be forgiven for mistaking it for the actual plot. The narrative voice—though being relayed by the then grown up protagonist—maintains a tone of childlike innocence that makes “The White Piano” so easy to sink into. Before long the reader is gently guided into the grandmother’s story, told concurrently in her voice, and that of the narrator. The setting, although containing a decent chunk of exposition for those who don’t know the early history of World War II, nonetheless drifts smoothly by on the wonderful voice and sets the tone and circumstances beautifully. All in all, “The White Piano” is a lovely, sweetly sorrowful story; a gentle, wistful take on ghosts and hauntings.

Caspar is your every day media consumer in Nick Wolven’s “Caspar D. Luckinbill, What Are You Going to Do?” Like everyone else, his life is flush with media. It’s ubiquitous, as well it should be. It’s what puts dinner on the table for Caspar. But his bread and butter turns sour one day when he finds himself the target of media terrorism: the sudden, uncontrollable assault of unpleasant, violent, and nasty current events from a country no one has ever heard of. As he’s bombarded with pictures of unspeakable crimes against humanity, as the media he has come to love and trust name him as complicit in his complacency, one by one the people in Caspar’s life shun him, unable to take the violent imagery that he is slowly becoming numb to. If Caspar has any hope of salvaging his life and sanity, he’s going to have to use all the tools of his former life to fight media firestorm with media firestorm.

“Carspar D. Luckinbill, What are You Going to Do?” is a humorous, tongue-in-cheek story that takes a close look at the prevalence of media in our lives. Living as we do in a time when none of us can expect to be free of the media’s vast reaching arm—or indeed, even want to be free—“Caspar D. Luckinbill” takes this to the extreme and redefines oversaturation. There are many clever commentaries on contemporary society sprinkled throughout the narrative: how our tech-coddled lives shelter us from the ongoing horrors of the world, how interconnectivity makes it easier to shirk blame and responsibility, and how every convenience in our lives helps to contribute to inconvenience or even suffering in someone else’s. This comedic scrutiny of first world living is sure to make even the most cynical of readers squirm a little under the phantom hand of guilt.

Being eleven is great for Theodore in “Robot from the Future” by Terry Bisson. You get all sorts of new freedom, independence and sometimes, if you’re lucky, you get to meet a robot. From the future. Unfortunately, the robot is in a bit of a pinch. A time pinch. It needs to get back home before it gets in trouble, but it needs gasoline to do it. All the gasoline in the world has been impounded though, and even pooling his resources with Grandpa R, they don’t have enough money to buy any on the black market. This is double unlucky, because the robot has no problem with dropping a casual threat of murder if it doesn’t get what it wants.

“Robot from the Future” is very much a story about the interesting little quirks of the world, rather than the plot itself. Although the robot is very vague about what the distant future is like, Theodore and Grandpa R are equally vague about the future world that they occupy as well. The three of them drop snippets of interested bobbles however, that the reader soon picks up greedily as one more piece of a vast puzzle. The characters truly live seamlessly in their world, bringing a depth to the story that exhaustive exposition would paradoxically remove from it.

It’s been ten years since Johnny has seen his hometown in Leo Vladimirsky’s “Squidtown.” Ten years of life spent in a prison in the Islamic Republic of Texas, a failed insurgent, a prisoner of war. Now back and with his sister Ana, Johnny sees that home really isn’t what it used to be. With all of Ana’s planning and building and revitalizing, Squidtown is growing, if not quite prospering yet, and the influx of tourists from the city is gentrifying its previously rough edges. No, home just isn’t home anymore, but how much of a claim does Johnny even have on the Squidtown he abandoned ten years before?

There’s an expectation in all of us who have lived a good distance from home for a length of time, that the place we left however many years before will be exactly the same when we return. Places, however, change just as much as people, not only in appearance but in mood and atmosphere as well. Yet even as we know things must change, the time capsule expectation remains. “Squidtown” exemplifies this dichotomy, and while the fictional island in Vladimisky’s story is likely a great deal more dystopian than the hometowns of many readers, Johnny’s return to and subsequent disappointment with “Squidtown” will resonate with anyone who has ever lived away from home. The setting is gritty and so are the characters. Told almost as a vignette into Johnny’s life, the reader is made to feel the protagonist’s distinct discomfort in being in a place he both recognizes and in which he feels alien. The ending, likewise, is very cleverly worded, and makes readers want to go back and pick through the prose for other tantalizing turns of phrase that sweeten—or sour—the story in just the right ways.

Hilil is a twiner in Betsy James’s “Touch Me All Over.” She knows all the knots there are in the world, by name and by make. There’s nothing that she can’t weave together and no one else who can match her skill. All of that unravels however, when Hilil finds a mysterious glass knife in the midden. Suddenly, nothing Hilil touches can stick together anymore. If it’s been made it falls apart as soon as it comes in contact with her skin and there’s nothing that she, her family or her people can do about it. All that is left is for Hilil to leave, before she unravels the whole entire world.

“Touch Me All Over” wanders around settings and moods, taking the reader on a journey that can’t be easily predicted. A lovely piece of cultural fantasy, the prose is lilting and hypnotic, easily drawing the reader into the narrative. While at the end I was left wishing more had been done to explain how the curse could be lifted, perhaps this is for the better, to preserve some of the nearly Disney-esque magic of the story.

Raffalon has fallen in with some bad company in Matthew Hughes’s “Telltale.” More specifically he has taken the wrong job from the wrong client. As a professional thief, Raffalon knows that any sort of dealing with a wizard is delicate and dangerous business. When he activates a magical trap retrieving an item for his latest client, Raffalon suddenly finds himself whisked away to a gray fishing village, amid a population who are conspicuously expecting him. Now tasked with finding a mysterious treasure in an enchanted forest, Raffalon has few options for escape and only one, equally mysterious source of companionship.

Even though the adventures of Raffalon the thief have been spread out over multiple short stories, “Telltale” is an entirely self-contained story that doesn’t assume the reader is already familiar with the character. Hughes neither over-explains nor hoards details, giving the reader the feeling of a natural character and world, even if they are experiencing it for the first time. Raffalon is a casually charming character, and set alongside neat, unobtrusive prose, “Telltale” is an easily digestible fantasy adventure story.

Somewhere in North Carolina is a forty-acre patch of land that is just wrong. Animals won’t enter it, native peoples wouldn’t populate it, and anyone who is either brave or stupid enough to traverse it comes into horrible misfortune. In Albert E. Cowdrey’s “The Visionaries,” Jimmy and Morrie and their paranormal cleansing services have been tasked with ridding the area of whatever bad mojo is hanging around in there. With Morrie’s uncanny sixth sense and Jimmy’s head for business, their trip to North Carolina should be as any other day on the job. But whatever malicious energy has been collecting in the area has been waiting a long time to unleash its evil and no one, certainly not a pair of paranormal investigators, will stop it now.

Cowdrey takes all the elements of a good story—interesting characters, a compelling mystery, smooth backstory—and combines them in just the right amounts to create a well-rounded horror mystery in “The Visionaries.” The investigation part of the story, which necessitates a lot of exposition, is told naturally and succinctly, neither bogging the story down, nor leaving the reader scratching his head. The short epilogue likewise draws together what feels like a too sudden conclusion to the events of the story, giving the reader further implications to ponder after the final sentence.

In “Braid of Days and Wake of Nights” by E. Lily Yu there are two things that Julia knows: her best friend is dying and a unicorn is loose somewhere in Central Park. While Vivian seems content to let the cancer take her from the world, Julia grasps at straws for any possible cure, no matter how impossible or miraculous. During the day she works and visits her ailing friend, but at dusk she stalks the park, searching for the illusive white horse that could be Vivian’s only salvation.

A sweetly sorrowful story, “Braid of Days and Wake of Nights” is a fairy tale for adults. It takes the harsh unfairness of life and glazes it with the fantasies of youth. As a short story with multiple interwoven threads, the pacing is remarkable, building and releasing tension at precisely the right spots to keep the reader interested. There are pleasant whiffs of Peter Beagle’s “The Unicorn Sonata” in the early part of the story. Beagle himself is referenced along with other fantasy notables, effectively tying the real world and a fantasy plane together in a way that is both unlikely and reasonable. But the ending is where the story really shines. The bitter-sweet conclusion is exactly the sort of mature end that the reader expects throughout the narrative.