For this issue we offer a split review; C. D. Lewis & Victoria Silverwolf each review a portion of the stories.

Asimov’s, September/October 2023

Asimov’s, September/October 2023

“Deep Blue Jump” by Dean Whitlock

“The Ghost Fair” by Lavie Tidhar

“The Unpastured Sea” by Gregory Feeley

“The Pit of Babel” by Kofi Nyameye

“Tears Down the Wall” by Michèle Laframboise

“The Water-Wolf” by Anya Johanna DeNiro

“In the Fox’s House” by Lisa Goldstein

“The Dead Letter Office” by David Erik Nelson

“Six Incidents of Evolution Using Time Travel” by Derek Künsken

“The Break-In” by Kristine Kathryn Rusch

♠ ♠ ♠

“Deep Blue Jump” by Dean Whitlock

“The Ghost Fair” by Lavie Tidhar

“The Unpastured Sea” by Gregory Feeley

“The Pit of Babel” by Kofi Nyameye

“Tears Down the Wall” by Michèle Laframboise

“The Water-Wolf” by Anya Johanna DeNiro

“In the Fox’s House” by Lisa Goldstein

Reviewed by C. D. Lewis

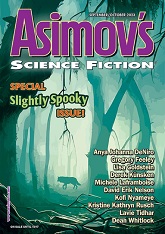

From this issue of Asimov’s Science Fiction Tangent reviews ten new pieces consisting of five novelettes, four short stories, and a novella. The issue also offers readers a collection of recommendations in the form of its Readers’ Award results.

Dean Whitlock‘s “Deep Blue Jump” opens on a child who barely survives delivery to a desert farm’s slave foreman. The conflict arises not from some new technology or social problem but an old one: exploitation of the powerless by the greedy, under the aegis of the corrupt. The story’s speculative element is the bluedream plant and the dreamberries it grows on vine nets that hold a child’s weight as long as one doesn’t slip and fall out of sight, never to be seen again. “Deep Blue Jump” uses the fictional berry to sketch the miserable lives of child victims of real-world topics: narcotics, human traffickers, corruption, addiction, and other miseries that thrive when government fails to deliver equal protection of the law. “Deep Blue Jump” offers sympathetic characters, high stakes, and a feel-good ending built on a climactic reveal. Readers specifically interested in science fiction may find the story could as easily have been told without the fictional berry, and while there is surely some value in raising awareness of drug cartels’ broad host of terrible crimes (as with any atrocity one would like to see exposed and ended) the work offers no insight to what might be done except to find allies to assist one’s escape. On the upside, a reader who invests emotionally in the protagonist may delight in the unexpected gifts that save her life. The fact she shares her rescue makes it feel like she accomplishes something in the climax; however, the protagonist’s success in the climax flows not from a hard character-defining choice nor the kind of clever reasoning for which science fiction is known—it flows from a secret revealed by an unexpected supporter, in the sort of solution one might find in a just-desserts fairy tale.

Lavie Tidhar‘s “The Ghost Fair” is a science fiction short story, told mostly in flashback, and set in a future where physical coins’ value flowed from the virtual currency their encoding represented in the virtual world. It’s that virtual world that gives rise to the story’s title: some of the future’s communities embed cyberpunk-style interfaces into their members, enabling upload (or partial upload) to allow (at least some of) a person to persist after death. The fair itself is an SF fantasyland of lab-bred T-Rex steak vendors, exotic travelers, and cultural fusion. Hired to escort a wealthy outsider to the fair, the protagonist escorts the reader past a host of glorious science fiction props and scenery until the foreshadowed showdown reveals what the hinted-at conflict has been about all this time. Feels like a fusion of noir and SF. Fans of cyberpunk will enjoy familiar elements. Recommended.

Gregory Feeley‘s short story “The Unpastured Sea” is an excerpt from a novel that has been in process long enough that an earlier installment, published in 1986, has been cut from the book because the science hasn’t held up. A background like this gives strong hope for a solidly-grounded hard-SF short story, provided the excerpt manages to embrace a story arc. The piece opens as a story within a story: a child relating a fable to other children. The word count invested in the narrator’s elaborations on the fable slows the feel down, and since no particular stakes are established at the outset one may need some commitment to progress toward something that not only depicts SF scenery, but also the feeling of a story. Feeley does deliver solid SF scenery, with descriptions of travel and distance and the physics of zero-gee structures clearly thought through with some care and awareness. Unfortunately, the description of orbital stations’ inhabitants’ longing for a future on one of Neptune’s various orbiting bodies can resonate a bit too easily with a reader’s growing longing for a gripping story problem; the fact of preparation and uncertainty about the future isn’t so exciting as to represent a hook. Dry reference to love affairs while the years pass waiting for something to happen might explain how the main character anesthetizes himself while he waits, but provides little aid to the needy reader. When a shipboard emergency does materialize, it’s got good science fiction detail. It’s a long wait getting there. In a traditional SF climax, the protagonist leverages knowledge of physics or a novel use of technology or otherwise reasons through to victory, but the climactic resolution in “The Unpastured Sea” seems a gift from a prepared mission planning organization rather than a result achieved by a successful protagonist.

Presented as an excerpt from a post-apocalyptic holy book complete with Biblical sentence structures and numbered verses, Kofi Nyameye‘s “The Pit of Babel” depicts mankind’s effort to solve the energy crisis with geothermal energy in the face of Lucifer’s many stratagems to thwart their common goal. Leveraging a classic try/fail cycle (and Lucifer’s entertaining ambitions), “The Pit of Babel” escalates the stakes and increasingly intertwines Lucifer with the fate of the mortals whose material salvation he seeks to thwart. Humorous. Recommended.

Michèle Laframboise‘s “Tears Down the Wall” is a police thriller set in a futuristic cityscape that blends a physical environment of cleanliness and order supported by ubiquitous robot assistance with a social environment of class separation and corporate oppression. In the colorful dawn wall-clinging snail-tents creep earthward and unhook as the light changes, to deflate at the foot of the buildings to create the image in the story’s title. The protagonist, a cop who depends more on robots than crime scene techs, investigates the death of a man skewered by anti-homeless spikes after his tent falls from a building face. Worldbuilding slows reader interested in the cop’s career or the homicide investigation. Rather than invest early word count in aspects of the case that could connect a reader emotionally to the protagonist or the victim, “Tears Down the Wall” focuses on what the cop expects robots to do to support the investigation and the technology they employ to do it. An impatient reader might miss the police procedural turning into a high-stakes drama: we’re seven pages in before a witness explains what the deceased did that drew enemies who might have him assassinated, and what kinds of social forces could lie behind the murder. Once the protagonist begins examining evidence, Laframboise proves capable to execute key police procedural elements to sketch the investigation’s subject and frame the crime, following leads and discarding misdirection to zoom in on an answer. A high-stakes rooftop climax resolves in a science-fiction resolution involving cooperation and creative use of tools and available skills.

Anya Johanna DeNiro‘s “The Water-Wolf” is a weird fantasy of transition involving time travel, cultural barriers, geographic inundation, and moving from childhood to adulthood and from dreamlike states to consciousness or from male to female. As one might imagine, the piece is rich with elements that depict otherness, self-discovery, rejection, solitude, survival, and changes in perspective. Although the story seems to unspool in a fugue state, moving through time as across landscape, consistent in mood rather than logic or time or geography, it does have a story structure: it is a survival story structured as a revenge plot. The protagonist, fleeing miseries at home, overcomes adversity on a journey, gets advice and instruction, and is returned home richer, loved, belonging, and empowered to crush the protagonist’s enemies with a spoken wish. Readers who prefer a climax in which success and failure in pursuit of a character’s needs and goals depends on the protagonist’s high-stakes character-defining choice may wish to be aware “The Water-Wolf” depends for its climax upon divine powers gifted to the protagonist and employed without personal risk. As with many survival stories and revenge plots, the story depends for the emotional impact of its climax on the audience’s desire to see the protagonist succeed and the adversaries crushed.

Set in a modern world on the eve of the protagonist’s ex returning with his new love to the house she lost in divorce, Lisa Goldstein‘s “In the Fox’s House” doesn’t immediately reveal itself as a fantasy. Soon, though, we learn fantasy creatures can be as unpleasant, oppressing, and controlling as in her freshly-ended marriage, and accepting the objectionable for convenience is no better strategy with fantasy creatures than with controlling husbands. The heroine prevails through wit and newly-acquired wisdom.

C. D. Lewis lives and writes in Faerie.

♠ ♠ ♠

“The Dead Letter Office” by David Erik Nelson

“Six Incidents of Evolution Using Time Travel” by Derek Künsken

“The Break-In” by Kristine Kathryn Rusch

Reviewed by Victoria Silverwolf

Anchored by a new novella from a prolific, award-winning author, this part of the magazine also offers a dark fantasy (justifying the proclamation on the cover that this is a Special Slightly Spooky Issue) and a fictional scientific article.

The protagonist of “The Dead Letter Office” by David Erik Nelson is a victim of revenge porn. She changes her name, leaves her home town, and gets a job in a postal facility. A letter addressed to Satan, thought to be a child’s error for Santa, begins a bizarre journey into a strange world, involving her past trauma.

This story is actually a lot weirder than I have made it sound, as the main character encounters supernatural beings and learns something about the nature of reality. It is the only work in the magazine that requires a content warning for nonconsensual sexual material. Personally, I thought the mention of extreme torture (not explicitly depicted, but a major part of the plot) was worthier of such a warning. In any case, it is most appropriate for mature readers of horror fiction.

As its title implies, “Six Incidents of Evolution Using Time Travel” by Derek Künsken consists of half a dozen examples of how alien organisms make use of time travel to perpetuate their species. The author shows great imagination and knowledge of both physics and biology. This tour de force of imaginary science can be admired as an intellectual exercise, even if it is not a fully developed story.

In “The Break-In” by Kristine Kathryn Rusch, armed mercenaries break into a warehouse in order to obtain valuable items for their employer. They don’t know that security is watching them. A cat-and-mouse game results, eventually resulting in a violent battle.

I have deliberately avoided mentioning the speculative content of this novella, because it is essentially a suspense story of a heist gone wrong. Although there is quite a bit of advanced technology involved, it is more likely to appeal to readers of crime fiction than science fiction.

The author uses multiple points of view to create a sense of tension. To some extent, this makes up for the fact that both the mercenaries and the security forces seem very ill-prepared for the situation, which tends to strain credibility. The reader is likely to be unsure who to root for, so the fate of the various characters is less effective than it might have been.

Victoria Silverwolf doesn’t live or write in Faerie.