“The Nameless Dead” by Kristine Kathryn Rusch

“The Errata” by K.A. Teryna (Translated by Alex Shvartsman)

“Planetstuck” by Sam J. Miller

“Night Running” by Greg Egan

“The Repair” by Mark D. Jacobsen

“Ernestine” by Octavia Cade

“The Case of the Blood-Stained Tower” by Ray Nayler

“Wanton Gods” by Sheila Finch

“The Queen of Rhode Island” by Bruce Sterling & Paul Di Filippo

“The Breaking of the Vessels” by Gregory Feeley

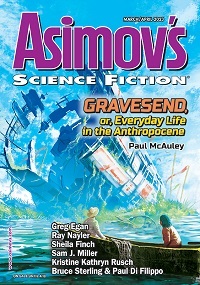

“Gravesend, or, Everyday Life in the Anthropocene” by Paul McAuley

Reviewed by Geoff Houghton

The opening novelette: “The Nameless Dead” by Kristine Kathryn Rusch is set on a later stage colony and spaceport planet in a future century. The first person protagonist has selfishly and impulsively abandoned her husband and infant child in the certain knowledge that the nature of the not much faster than light star-drive that carried her there has irrevocably made that a one-way journey. The technology of that star drive and the cheap and near instantaneous communication system that links home and colony worlds are not explained in any detail, but their characteristics are critical to her subsequent career and the very existence of the story.

Our protagonist has made a successful business out of using the instant communication system on behalf of other star-farers in order to trace the history of those left behind by the time dilation of star travel. She is asked by the retiring Port Coroner to use those skills in reverse to investigate the past of some of the hundreds of travellers whose mysterious deaths have puzzled that officer over the years. Her investigation uncovers a widespread and ancient crime network, but the author’s main interest is not either resolution or prosecution of the crime itself but the impact of her discovery on our unsympathetic and rather unlovable protagonist.

“The Errata” by K.A. Teryna (translated by Alex Shvartsman) is the name of a much slower-than-light Ark that has just departed from a near-future Earth on the first few years of its thousand year journey to a new world. The story is told from the point of view of a teenaged boy who is expected to live, age and die as a part of the multi-generational crew who must maintain the Ark on its long, slow journey.

High on the Alpha deck are the officers and executives of the Ark, most of them in a deep cryo-freeze that may permit them to actually see New Earth for themselves, but the role of the thousands on the lower decks is merely to ensure the safe passage of those chosen few to their new home.

This is essentially a rite of passage story carrying the protagonist from earthborn child to an accommodation with adulthood and a life as a spacer via an almost uniquely Russian experience. At the same time that he is newly buoyed up by meeting the comradeship and cheerful enthusiasm of the early hero projects of real communism he also bumps violently against the distorted capitalism and kleptocracy that so often is the darker side of such a regimented society. Overall, this is an insightful work offered by a keen-eyed observer from within a world that most Western readers will have never known.

The third tale is “Planetstuck” by Sam J. Miller. In contrast to clumsy NAFAL or Generation spaceships, this far-future universe is linked by gates that allow a traveller to step from world to world with shirtsleeve ease. So simple and ubiquitous is this form of transit that many routes are free of any toll and few cost more than credit required for a cheap meal in order to step across thousands of light years.

This ease of travel has generated a tension between those who feel themselves citizens of the whole grid of worlds and those who feel an atavistic loyalty to a single planet of origin, and some of those “Planetstuck” individuals are willing to do more than grumble.

Our protagonist has been the victim of a plot by a “Planetstuck” cabal to destroy all of his home world’s gates in a single strike. That has taken his planet of origin off the grid entirely for centuries to come, since replacement gates must be sent by slower than light robotic star-ship. He truly believes that he has adjusted to this loss until he finds a coin from his home world, dated after the cataclysmic separation and realises that somewhere a gate still remains open.

He discovers that his find was not entirely by chance, that the last gate is controlled by the very organisation that destroyed all of the publically known gates and that they have a use for him in their future schemes. The remainder of this novelette explores what our protagonist might be willing to do and risk for the chance of a route back home.

“Night Running” by Greg Egan is a novelette set in a very near-future Australia.

Our workaholic protagonist decides that there are not enough hours in an ordinary day for both work and sleep. His in-story solution is to purchase an over-the counter drug whose characteristics and side effects would have certainly led to its immediate ban from the real world outside of highly specialist units. This mythical drug substance essentially automates the otherwise sleeping user so that they can perform all manner of routine and mundane tasks whilst functionally asleep. After a series of near disasters that only go to show how dangerous such a medicine would be if its untrammelled sale were actually to be allowed, our protagonist discovers that he is permanently addicted and under this medicine’s control, yet still considers that this is a matter which should be dealt with personally, without any professional input.

An author is the absolute ruler of his own universe, so, in-story, our protagonist is successful in that mission, with a novel and clever scheme to convert his addiction to a useful end. In the real world, there is a stereotype that Australians are notoriously independent and resourceful, but there is such a thing as too much self-reliance, Greg!

In the short story: “The Repair,” Mark D Jacobsen paints a frightfully vivid picture of a dark and dismal future America in which a single error of judgement or even an ill-chosen remark to or about the wrong person can devastate a career and ruin the rest of a life. AI and robotics have advanced to the point where real privacy is a rare and precious commodity and unescapable computer trolls can blight your life more pervasively than a skunk’s smell.

The protagonist and his client have both suffered such a fate, he because he accidentally damaged the property of a vindictive billionaire, she as the not entirely innocent victim of an overly woke culture.

The narrator has coped with his undeserved fate far more robustly and successfully than the rather less resilient, semi-mad, woman whose intemperate actions seriously damage his hard-won freedom. His final decision about how to respond to her need for help is more moderate and generous than she deserves and brings the only light into a well-portrayed but gloomily dark tale.

The next novelette is “Ernestine” by Octavia Cade. Ernestine is a young child lost in a spookily empty city after all the adults in her world have mysteriously puffed into non-existence. The city is contemporaneous Christchurch, New Zealand but there is no reason to assume that this unexplained supernatural event has not occurred across the whole world.

There are hints of the excessive behaviour predicted by the less supernatural classic “Lord of the Flies” in the response of many of the other children left behind by this cataclysm, but Ernestine is wise enough to steer clear of those bands. In fact she appears to be an extremely practical, resilient and very competent child, intelligent enough to avoid trouble, at least at present when homes, shops and warehouses still contain adequate stocks of necessary staples.

She is also assisted by either a spirit-guide, or possibly a computer AI, that purports to be the famous New Zealand born physicist, Ernest Rutherford. Her mystery guide gives useful advice to further prepare an already special child to survive even this disaster. The author has avoided too much detail of the bleak future that probably awaits these lost children and there is a tiny ray of light at the end of this particularly awful tunnel when the young Ernestine belatedly discovers that not every survivor is a self-destructive and unthinking tribal savage.

“The Case of the Blood-Stained Tower” by Ray Nayler is a novelette that transplants the sleuthing style of Sherlock Holmes to the Middle Eastern world of One Thousand and One Nights. The narrator takes the straight-man role normally filled by Dr Watson and the Holmes-like character is an urbane polymath Nobleman who assists the local Princely Bey by investigating the mysterious death of a rich merchant’s daughter caused by a fall from a great height onto the courtyard of a locked and barred mosque.

The author has made a considerable effort in the transfer of these characters from 221B Baker Street to Baghdad and no one should be surprised if they receive further cases in the author’s future works. In this specific case, a reader can either choose to read this quickly as a little light fun, or more carefully attempt to solve the mystery for themselves. It would be wrong to include any spoiler for the latter group of readers except for one reassurance. Given the 1001 Nights feel to the scenario, the reader may suspect any number of supernatural answers from giants and genii, multiplex of wing and eye (as in G.K. Chesterton’s epic poem, Lepanto) through to flying carpets, but the answer to the puzzle is available, although cleverly hidden in the text, and no magic is required.

The short story, “Wanton Gods” by Sheila Finch initially feels as if it is a work of fantasy, but that is because any sufficiently advanced technology is undistinguishable from magic to those who do not understand it (Arthur C. Clarke’s words, not mine), and the real location proves instead to be our own far distant future. Humanity has carelessly and heedlessly provoked a race of powerful and unpleasant aliens with the result that Earth has been devastated and its inhabitants are now hunted across the wastes that remain by the robotic servants of those vengeful extra-terrestrials.

There are also races of more benign aliens in the Universe who do not approve of what has been done to humanity. Their own advanced technology allows them to observe, but their equivalent of the Prime Directive forbids them from interfering until the day when one semi-autonomous observer-construct befriends a human girl-child and bends those rules. The offending construct must face the consequences of its interference in a court allowing no appeal and can expect precise justice rather than mercy.

This is an interesting volte-face from SF stories where lofty humans apply the Prime Directive to hapless and primitive aliens, and it is certainly the case that when the shoe is on the other foot it pinches rather more uncomfortably.

“The Queen of Rhode Island” by Bruce Sterling & Paul Di Filippo is a novelette that explores a significantly altered East coast of America where ecological breakdown has all but depopulated the planet. The human-descended Ribo folk are able to manipulate their own metabolisms and to live in perfect harmony with the Earth, whilst unmodified humans are almost a thing of the past. However, a few organised collections of these destructive pests remain in small but ecologically damaging settlements that most Ribo folk see only as a blight upon a wounded planet.

In Rhode Island, the especially peaceable Ribo inhabitants have even managed to live in a sort of uneasy truce with the local human village until a wandering Ribo hero attempts to single-handedly rid them of this infestation. The hero is massively endowed with brute force and destructive ability, but the pesky humans show that their strongest skill area has always been war and destruction and it is only when the hero is required to use his brains instead of his mighty limbs that the nest of humans can finally be cleared from the land.

The reader may or may not be able to easily identify with his own species being considered a pest, but it helps that the author does not take himself too seriously. So the writing style is very deliberately light parody and every major character is outrageously over the top; the spoiled Princess is really seriously spoiled, the brave hero is ridiculously bold and brawny, and the slow-moving Shaman makes Treebeard look positively hasty.

The last short story is “The Breaking of the Vessels” by Gregory Feeley. This tells of very distant descendants of humanity, deep in space and far into an alien future. The reader must cast aside any expectations that our species will remain unchanged by millennia of change around it and the human-descendants in this story appear more foreign in motivation and action than most SF aliens of different species.

The only novella in this issue of Asimov’s is: “Gravesend, or, Everyday Life in the Anthropocene” by Paul McAuley. This story is set in the Thames Valley estuary, UK in a near future where the developed world has belatedly yielded to ever increasing ecological shifts and mankind has finally and severely curtailed the consumer society. The culture that has replaced it is definitely lower impact and more sustainable, but may have too strong a flavour of the 1960’s Hippie world for the taste of some readers, especially those in red states in the USA.

The freedom permitted by the length of a novella has allowed the author freedom to develop his world and its principal characters so that they are believable and, in the main, sympathetic, but some readers may find the pace rather too slow. If your main reading interests are in exploring relationships and human interactions then this work may suit you, but if you seek action and real tension then you will suffer a real disappointment as even the apparent villains turn out to have a benign nature and good reason for their actions.

Geoff Houghton lives in a leafy village in rural England. He is a retired Healthcare Professional with a love of SF and a jackdaw-like appetite for gibbets of medical, scientific and historical knowledge.

Asimov’s

Asimov’s