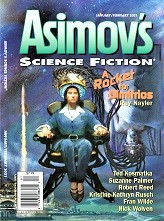

Asimov’s, January/February 2021

Asimov’s, January/February 2021

“A Rocket for Dimitrios” by Ray Nayler

“The Realms of Water” by Robert Reed

“No Stone Unturned” by Nick Wolven

“Table Etiquette for Diplomatic Personnel, in Seventeen Scenes” by Suzanne Palmer

“Hunches” by Kristine Kathryn Rusch

“Shy Sarah and the Draft Pick Lottery” by Ted Kosmatka

“Mayor for Today” by Fran Wilde

“The Fear of Missing Out” by Robert H. Cloake

“The Three-Day Hunt” by Robert R. Chase

“Humans and Other People” by Sean William Swanwick

“I Didn’t Buy It” by Naomi Kanakia

Reviewed by Michelle Ristuccia

American combat veteran Sylvia Aldstatt is the only person on Earth who can search dead criminal Dimitrios’ memories for crucial intel in “A Rocket for Dimitrios” by Ray Nayler. Racing against the ticking clock of decomposing neural pathways, Sylvia Aldstatt investigates Dimitrios’ claim of a second crashed extraterrestrial ship, after reverse-engineering of the first ship has raised her superiors to the top of the technological and political ladder. But the physical limits of ‘piloting the loops’ isn’t the only thing standing in Sylvia’s way; Dimitrios the informant somehow resists her dive into his self, as tight-fisted in death as he was in life, but now for reasons that have nothing to do with money and politics and everything to do with the final loss of his core identity. As Sylvia contends with the deadly international politics that killed Dimitrios and now threaten her own life, she must also navigate internal questions of the soul, of how power, or the lack thereof, can corrupt the paths of individuals and nations alike. Seeing through Sylvia’s eyes, readers get a taste of alien technology far beyond our current abilities, contrasted against humanity’s endemic struggles with war and discrimination. Nayler brings readers an adventure that’s as immersive as it is thought-provoking. “A Rocket for Dimitrios,” stands alone as an engaging and accessible novella for all genre readers, but spy novel enthusiasts will recognize the nod to Eric Ambler’s classic 1967 novel, A Coffin for Dimitrios. Readers who want more of Nayler’s fascinating alternative history SF can find Sylvia Aldstatt in “The Disintegration Loops,” published first in Asimov’s Nov/Dec 2019 issue and also now available on Ray Nayler’s website.

“The Realms of Water” by Robert Reed re-imagines Hannibal’s favorite elephant as an alien far removed from human life, as one surviving specimen of a species that communicates in electromagnetic waves and feeds off of ‘sweet electric’ juices. Like Hannibal’s elephants, the Great Many serve another species in war, crossing mountains and waters to do so. History buffs will find many similarities between the Carthaginian wars and the story that character Surus relates to Queen Lee in this story-within-a-story. Surus’ lengthy campaign summary may try some readers’ patience, yet this matter-of-fact biographical length also gives Reed the space to include many interesting SF details alongside references to Hannibal’s tactics. Bookending Surus’ story with Queen Lee’s trip across a desert adds meaning to Surus’ narration, inviting readers to question where servitude ends and companionship begins, whether you’re a war elephant or a junusian couple whose male half attaches itself permanently to the female half, remaining forever the smaller part of the coupling.

In “No Stone Unturned” by Nick Wolven, Martin fears his wife Anna’s erratic behavior signals a much larger issue, and he’s correct, though perhaps not in the way he thinks. A former astronaut, Anna now spends her days as a stay-at-home mother to Nick’s young son, Benji, with the help of nannybots and a daycare. Yet even the nannybots cannot keep up with Anna’s spurts of neglect. When Martin comes home to find Benji abandoned in an unsafe house during one of his wife’s strolls, he agrees to meet with a scientist who suspects that Anna’s trip into space changed her in ways the space program will never admit. Wolven invites readers to ask the question, what makes you, you? And once a change has taken place, does it matter what caused it? Throughout the story, the close-3rd-POV text focuses on Martin’s expectations and desires, especially around childcare. Astute readers might notice that while Martin displays the emotional attachment to Benji that he wishes Anna would, he too depends on others to care for his child, as the primary bread winner. The couple have relied on domestic robots to bridge any gap in parenting and physical presence, but technology can’t quite bridge the gap in how Martin envisions his life should be, versus what it is. “No Stone Unturned” contrasts humanity’s insatiable reach for the stars against one husband’s desperate grasp to save the marital bliss they both once thought they’d have. This story comes at a time when many working parents have suddenly been forced to work from home with their children underfoot, yet the themes of child-parent bonding and childcare will remain relevant long after such parents have returned to workplaces, and children have returned to schools. Wolven grabs the reader’s empathy as he subtly transforms a classic SF fear of technology into a deeper exploration of the role of love and affection in regards to duty and self-fulfillment. This chilling tale offers no easy answers.

Suzanne Palmer brings readers a delightfully comedic who-done-it set on a menagerie of a space station in “Table Etiquette for Diplomatic Personnel, in Seventeen Scenes.” Through Palmer’s strategic humor, readers soon identify the obnoxious Joxto as the main antagonists of newly appointed Station Commander Niagara, though she has yet to meet the infamous aliens herself. She’ll get her chance soon enough, as she must now prepare the station for the Joxto’s impending and unannounced arrival. Other issues soon demand the Commander’s attention, from a noxious food-smashing ceremony requiring her diplomatic presence, to the serious crime committed before the Joxto even arrive. As these wildly disparate clues spiral together, Palmer brings her station and the larger universe to life through the POV’s of several station inhabitants, painting readers a vivid picture through casually dropped space lore, a melting pot of clashing cultures, and truly alien extraterrestrials who resemble sea cucumbers, birds, and overly curious pumas. Running jokes and excellent comedic timing provide an enthralling mix of slap stick and sitcom drama, all centered around food. But don’t let the entertaining surface of Palmer’s light-hearted novelette fool you. One could say that the theme of greed, along with a fitting dose of poetic irony, provide plenty of food for thought.

The moment after Lieutenant Balázs’ starship bridge is breached and most of its bridge crew incapacitated, “Hunches” by Kristine Kathryn Rusch begins. Reeling from the unexpected attack, Balázs soon realizes he is the only crew member left conscious on the bridge, and so takes initiative to remove the mysterious fiery object that has punched a hole through the ship. Rusch brings us an action-packed story of split-second decisions and willing sacrifice, of heroic acts performed in the absence of sufficient information but with the help of a little luck and a lot of perseverance. Apt descriptions of Balázs’ trauma-compromised senses draw readers into the moment, heightening the ticking clock of compromised ship systems as he strives to save his fellow crew mates.

In “Shy Sarah and the Draft Pick Lottery” by Ted Kosmatka, Sarah’s employers crunch numbers to find individuals with the inexplicable talent of accidentally influencing the outcome of sports games to favor their preferred team. Sarah’s job is then to confirm the prospect’s talent in person, using her own talent to do so. When Sarah breaks protocol by informing their newest prospect of the larger game he’s being manipulated into, she risks more than her lucrative employment. In a story exploring free will in the face of practically omnipresent manipulation, Sarah gives her prospect the one thing he could never gain himself: the truth he needs to make a decision. Kosmatka’s idea of number-crunching to find magical talents, then bidding on the right to manipulate prospect’s lives, feels spine-shiveringly real in “Shy Sarah and the Draft Pick Lottery,” hitting close to home in our world of social media algorithms and online data collection.

GigTime worker Victor finds himself trapped in a poorly worded gig contract in the comedic SF story “Mayor for Today” by Fran Wilde. When Victor sees a gig that looks too good to be true, he accepts and travels half-way across the world in order to escape his cramped living space and the cycle of dead-end gigs he’s been stuck in since ‘the worst gig ever.’ While the village of Danzhai is indeed as picturesque as promised, the other shoe drops when Victor learns that another GigTime worker has successfully gamed the GigTime system, interfering with his own gig, trapping him and the village in a stagnant loop. From social media to legalese, Victor and his new friends must learn how to trick the cheater into a loophole of their own. Wilde’s caricature depictions add to the entertaining absurdity of “Mayor for Today,” bringing forth weightier moral issues through well-oiled social parody in a way reminiscent of Douglas Adams’ style.

In “The Fear of Missing Out” by Robert H. Cloake, new auto-personality technology promises to smooth over Candid’s social interactions at work and home. But when his first use of his auto-personality lands him a date, Candid must decide where the role of his auto-personality ends and the role of his true self begins. While most readers can relate to putting on a mask for different social situations, Cloake skillfully transforms this question of social anxiety into a sharper challenge involving our dearest social contracts. Hints of neurodiversity add depth to Candid’s moral dilemma. A re-readable, moving narrative with daring implications about honesty and relationships. For readers who wish to explore these concepts further, Cloake slips in a reference to “The Great Transformation” by Karl Polanyi early on in the story. In this expertly crafted story, every word and turn of phrase adds to the theme and drives the action, even the main character’s name.

“The Three-Day Hunt” by Robert R. Chase starts with medically discharged veteran Hammond setting out into the woods to rescue whomever—or whatever—was piloting the crashed UFO discovered by his dog, Tripod. The arrival of military personnel also searching for the alien soon complicates what Hammond sees as a simple search-and-rescue of a possibly injured person in need of help, as do he and Tripod’s old injuries. Chase interweaves Hammond’s backstory with the veteran’s present interactions with Tripod, presenting readers with an optimistic, character-driven story that’s less about first contact and more about our species’ capacity for co-existence and cooperation, despite our capacity for violence.

In “Humans and Other People” by Sean William Swanwick, urban salvagers Mitchell and his robot Simone scam residents of a flooded building into contracting their services to retrieve personal items from the supposedly unsafe complex. While there, Mitchell and Simone discover a secret that elicits opposite reactions from human and robot. Enticing readers from the start, outwardly cynical underdog humor brings us into a scammer’s POV in a future where ocean waters have risen and reached Atlanta. Yet it is Swanwick’s hints of optimism and compassion that flesh out his admirably complex characters. “Humans and Other People” takes readers on a surprisingly nuanced ride along the continuums of compassion and logic, optimism and cynicism, fair chances and scams.

In “I Didn’t Buy It” by Naomi Kanakia, readers follow robot Reznikov through the tragedy of his first owner and into his life as an ownerless, non-sentient service program. Where many robot stories focus on the question of sentience itself, Kanakia instead boldly centers on Reznikov’s lack of agency, shifting the focus to human characters’ reactions to him, to their ability to need and make use of him. Kanakia delivers an intriguing story where one character’s actions are the only real thing about that character, and any interpretation or emotion are all projections of our own selves. Readers might interpret this story any number of ways as they watch Reznikov fulfill a role in society and in his home life, performing actions we often associate with love and dedication. Economic storytelling utilizes telling versus showing in order to dispense of any mystery regarding Reznikov’s sentience.

Michelle Ristuccia enjoys slowing down time in the middle of the night to write, read, and review speculative fiction, because sleeping offspring are the best inspiration. Find her on Facebook and twitter @mrsmica.