Analog, November/December 2018

Analog, November/December 2018

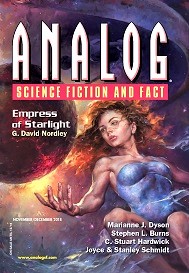

“Empress of Starlight” by G. David Nordley

Reviewed by Victoria Silverwolf

The latest issue of this long-running science fiction magazine offers a balance of stories set close to home and others encompassing the far reaches of time and space.

The protagonist of “Empress of Starlight” by G. David Nordley is a woman who is uncomfortable in the company of other people. She reluctantly agrees to join a small group of humans and aliens on a voyage to investigate the disappearance of a star, although she would prefer to go alone. After centuries of travel, endured by the members of the expedition because of suspended animation and the time dilation effect of relativistic speed, they arrive at their destination. A vast alien structure surrounds the hidden star. Investigation of the artifact reveals its dangers, and gives the protagonist an extraordinary opportunity.

This story offers an awe-inspiring vision of super-advanced technology of astronomical proportions, in the tradition of Larry Niven. The interactions among its characters are less effective. Their conflicts make them seem like adolescents, instead of highly skilled adults. Readers who prefer mind-expanding ideas to psychological insight will enjoy this tale of cosmic exploration.

“Pandora’s Pantry” by Stephen L. Burns involves a competitive cooking program on television, similar to Iron Chef and other such shows. A severe storm prevents two of the contestants from showing up. At the last minute, replacements arrive. One of them is a robot. When the storm causes a power failure, the competitors must work together to prevent a crisis.

This is a light, pleasant story, with likable characters. The idea that a fully functioning, sentient robot could exist in a world with no other futuristic elements strains credibility. Despite its implausibility, this is an enjoyable tale of cooperation, with a touch of humor.

In “The Gleaners” by Sarina Dorie, disembodied aliens are able to inhabit the bodies of humans, while the minds of the humans travel to the aliens’ home world. The narrator is one such alien, living in the body of a woman recently separated from her husband. The alien interacts with a man, and they learn something from each other. The main appeal of this quiet, undramatic story is its characterization of both human and alien.

The protagonist of “Smear Job” by Rich Larson undergoes a strange punishment for the crime of a consensual sexual relationship with an underage girl. The authorities modify his perception, so that anyone under eighteen years old appears only as a blur. He goes on to have a normal life, but the change in his vision leads to sad consequences. This brief story has a strong emotional impact.

“A Measure of Love” by C. Stuart Hardwick takes the form of a diary. The narrator, raised by a robot when she was a child, rescues the inactive machine from storage when she grows up. Programmed only for childcare, it struggles to find a place for itself in a new world. This is a moving story, although its structure makes it a little difficult to follow.

“Learning the Ropes” by Tom Jolly deals with an experimental project to connect two asteroids with a long cable made from a super-strong material. The supposed intent is to send them spinning in the solar wind to produce energy. In fact, the woman who suggested the scheme has an ulterior motive. This is a clever story, but its scientific details are likely to go over the head of a reader who is not technologically sophisticated.

“Hubstitute Creatures” by Christopher L. Bennett is one of a series of stories set in deep space in the far future, when so-called hubpoints allow interstellar travel. The problem is that no one can predict where hubpoints are located, or where they lead. The main character has an ancient map of hubpoints, which she keeps secret. After a careless conversation, an acquaintance steals the map, with the intent to sell it to the alien species that controls the hubpoints. The protagonist and her friends travel to the aliens’ world to retrieve the map. They use biotechnology to disguise themselves as members of other alien species. Complications ensue.

This semi-comic adventure moves at a rapid pace. The many different aliens involved show a great deal of imagination. Unfortunately, the story spends too much time dealing with the romantic entanglements of its characters.

“The Light Fantastic” by J. T. Sharrah features aliens whose gaseous form and incredible powers make them seem like the djinn of legend. An archaeologist investigating the ancient ruins on their planet reveals his greatest desire to them. The result is unexpected.

Despite a large number of science fiction trappings, this is a really a variation on the familiar fantasy theme of granting a wish. It begins with a striking image, which proves to be of great importance, but the plot is a simple one.

“The Jagged Bones of Sea-Saw Town” by Marissa Lingen takes place in a coastal city in the far north. Over many centuries, the inhabitants had to move the city many times, as seas levels rose and fell. Two people discuss whether it makes sense to continue shifting the city this way. They also talk about the possibility of using biotechnology to recreate caribou, which are extinct.

This story has many interesting ideas, but is mostly conversation. Although it takes place more than one thousand years from now, the characters do not seem any different from people of our own time.

The title character in “Sandy” by Bruce McAllister is an alien child on Earth. Most human children bully her because of her strange appearance, but the narrator becomes her friend. A few months later, the relationship between humans and the aliens changes in a dramatic way. In a few pages, the author creates a powerful story of the way in which small actions can have profound consequences.

“Dad’s War” by Filip Wiltgren is a darkly satiric tale set in a world dominated by business corporations. Brand names take the place of nations. Companies wage war against each other. Those who live outside of a corporation must survive on basic rations, without the advantages offered by loyalty to a particular brand.

This story paints an intriguing picture of a semi-dystopian future. The ending is ambiguous, offering both hope and a sense that rebellion against the corporations is pointless. The narrative style is jumpy, and not all the details about this society are clear.

“Ashes of Exploding Suns, Monuments to Dust” by Christopher McKitterick is a dense, complex novelette that takes place over thousands of years. Long before the story begins, humanity colonized many planets. Earth ruled these worlds as an empire. Much later, after the planets won independence, Earth ships return to one of the worlds to reclaim it. The colonists defeat the Earth fleet. In retaliation, Earth sends an overwhelming force to destroy the planet. Only the crew of a single warship survives. They go into suspended animation and begin a journey that will last for millennia, in order to revenge themselves.

Multiple flashbacks depict the voyage of vengeance, the destruction of the colony planet, and the narrator’s personal life in counterpoint. The author manages to combine space opera, sociological speculation, and introspection into a unified whole. The contrast between vast lengths of time and one person’s life makes the story a compelling one.

“The 7 Most Massive Historical Mistakes in Gunmaster of the Carlords” by Eric James Stone is not a Probability Zero offering, but it could easily fit into that category. Told from the point of view of someone living in a technologically advanced future, this little joke story involves virtual reality. The narrator criticizes a work of VR fiction for its inaccuracies, such as depicting automobiles as animals. It quickly becomes clear that the narrator knows as little about the past as the creator of the VR does. The end allows the author to wink directly at the audience. This lighthearted bagatelle should raise a smile.

All the characters in “The Ascension” by Jerry Oltion are members of a bizarre alien species. They obtain memories and aptitudes from others of their kind by devouring part or all of their bodies. The story involves the ruler of the aliens, and a child undergoing a test to see if it is worthy of being eaten by the leader. The impending arrival of visitors from another star complicates matters. The child uses the opportunity to turn the tables on the ruler.

The weird biology of the aliens holds the reader’s interest. The way in which the consumption of their fellows effects their minds is not always easy to understand.

In “Left Turn” by Jay Parks, a company specializes in offering creative strategies for businesses facing crises. Their latest client is the head of an asphalt company. Efficient self-driving cars and extensive ride sharing threaten to cause a drastic decrease in road wear. The consultants come up with a plan to ensure that the streets will still need plenty of asphalt for repairs.

This wry, ironic story reads like something that might have appeared in Galaxy magazine during the golden age of satiric science fiction. Anyone who has ever been stuck in a traffic jam, or hunted unsuccessfully for a parking spot, will appreciate it.

“Body Drift” by Cynthia Ward is subtitled un hommage à Frederik Pohl. It obviously draws its inspiration from his classic story “Day Million.” As in that famous tale, a sardonic narrator tries to explain how people live in the far future to a person of the present day. The ending ponders the question of what it means to be human. The author provides a worthy pastiche of the original.

The issue concludes with “Mixipoxi Learns to Drive” by Joyce and Stanley Schmidt. Before the story opens, an alien criminal with dangerous technology arrived on Earth. Others of its species came to stop it. One of them secretly chose to work with humans instead. Now it has to meet with one of its fellows to report on the progress of their mission. Because this meeting has to take place away from the sight of human beings, and is located at a hidden spot on a dirt road, the alien must learn how to drive a car so it can take itself there.

Despite the serious nature of the events leading up to the plot, this is an upbeat tale with a generous serving of comedy. After many misadventures, a happy ending ensures that everything will work out for the best. Younger readers would be the best audience for this story.

Victoria Silverwolf is not technologically sophisticated.