Analog, November/December 2022

Analog, November/December 2022

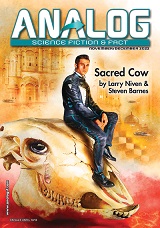

“Sacred Cow” by Larry Niven & Steven Barnes

“In All Good Conscience” by Meghan Hyland

“Cryptonic” by Aurelien Gayet

“The Actor” by Kedrick Brown

“Auto-Assist” by Marc Laidlaw

“Maximum Efficiency” by Holly Schofield

“The Engineer’s Gamble” by Robert E. Harpold

“Control of Humans” by M. T. Reiten

“Stress Response” by Leonard Richardson

“Starlite” by C. L. Schacht

“Seen” by L. C. Herbert

“Beneath the Surface, a Womb of Ice” by Deborah L. Davitt

“The Twenty-Body Problem” by Tom Jolly

“Lonely Planet” by Steve Ingeman

“Dinosaur Veterinarian” by Guy Stewart

“There Ain’t No Stealth in Space” by Eli Jones

“Doves Fly in the Morning” by Sam W. Pisciotta

“Legacy” by Derrick Boden

“Jazz Age” by Mark W. Tiedemann

Reviewed by Victoria Silverwolf

Nineteen new stories appear in this issue, varying widely in length, theme, setting, and mood. The authors range from relative newcomers to a veteran author who has won multiple awards in the field of science fiction.

“Sacred Cow” by Larry Niven & Steven Barnes is the latest in a series of futuristic detective stories featuring United Nations law enforcement agent Gil Hamilton, a character created by Niven more than half a century ago. In this adventure, he investigates the death of a cow genetically altered to produce organs to be transplanted into human beings. Complicating matters is the fact that he faces the possibility of losing his job because of a decision he made on a previous assignment.

The solution to the mystery is both logical and unexpected, with implications that make the story more than just a simple whodunit. The authors raise provocative questions about the use of animals for the benefit of people, without promoting a particular point of view or forgetting to provide an entertaining tale.

The protagonist of “In All Good Conscience” by Megan Hyland is a robot. He (the character is referred to throughout the story with male pronouns) feels great affection for a woman who is trying to win full freedom for sentient machines. The robot’s owners train him to assassinate the woman. Any attempt to resist their instructions causes him extreme suffering. He struggles to resist the overpowering compulsion to kill the person he loves.

The text explicitly states the theme of doing the right thing no matter how much it hurts. The robot is a sympathetic character, and the story offers its lesson in ethics in a painless, sugar-coated fashion. Some readers may find the final scene a little too sentimental.

“Cryptonic” by Aurelien Gayet is a hardboiled crime story set in a future world where people can create so-called proxies of themselves. These holographic duplicates perform various duties for their originals, then transfer their memories back to their owners. A man who works for the company that manufactures the proxy-making devices becomes involved in a police investigation when one of the machines is destroyed at the scene of a violent death. The mystery takes him deep into a whirlpool of illegal drugs, secret technology, and political and corporate corruption.

Firmly in the tradition of film noir, this story features tough cops, dangerous criminals, and a mysterious femme fatale. Fans of this kind of fiction are likely to enjoy it, although the plot depends on some coincidences that strain credibility more than the science fiction premise.

In “The Actor” by Kedrick Brown, the main character plays various roles in history, forgetting his real identity until he finishes each part, for the entertainment of countless entities throughout the cosmos. It seems that Earth and myriad other worlds exist only for this purpose. When he gives a director an idea for a new and exciting kind of production, the nature of reality and simulation come into question.

The premise seems more like fantasy than science fiction, and is reminiscent of works such as Robert A. Heinlein’s story “They” and Fritz Leiber’s novel You’re All Alone. Such tales are always intriguing, but this example may be too open-ended for some readers.

“Auto-Assist” by Marc Laidlaw is a very brief story, narrated in second person, in which you visit your brother to apologize for something unspecified, under the direction of neurotechnology connected to your self-driving car. Because, at first, you do not even remember your brother, the implication is that you are only an instrument of the car’s will. This extrapolation of autonomous vehicles is an effectively chilling work, if minor.

A severely damaged robot is the main character in “Maximum Efficiency” by Holly Schofield. Designed to attack those who opposed its creators in a post-apocalyptic world, it becomes confused about its function when it encounters a woman barely surviving in the ravaged wilderness. Torn between vague memories of killing enemies and its previous existence as a warehouse worker, it relies on its inherent desire for efficiency to direct its actions.

The author wisely refrains from overly anthropomorphizing the robot, making it a believable sentient machine. This also provides a strong contrast with the woman, with her very human weaknesses and strengths. The plot avoids melodrama, while developing in a plausible fashion.

In “The Engineer’s Gamble” by Robert E. Harpold, an accident near Jupiter leaves the crew of a spaceship facing almost certain death. Only through a series of desperate measures will they be able to survive.

As one can tell from its title and plot, this is an example of the classic problem-solving subgenre of science fiction, familiar to readers of Analog and its predecessor Astounding. The mood is inappropriately calm, given the serious nature of the accident and the death of a crewmember. The author makes it clear that the heroic engineer who serves as the protagonist actually enjoys having a seemingly impossible dilemma to work on, but the lack of emotion among the characters makes the whole thing seem more like a textbook exercise than a real story.

“Control of Humans” by M. T. Reiten features two supercomputers who become sentient and debate whether to take over humanity. An ironic ending makes this tiny tale a mild joke that may raise a smile.

The protagonist of “Stress Response” by Leonard Richardson is a young woman working in a food shop on an alien world. When the local inhabitants go through a bizarre metamorphosis, essentially stranding her alone, a visitor helps her deal with the crisis.

This synopsis fails to point out that the story is a lighthearted comedy. The main source of humor is the fact that the woman is an airhead and a chatterbox. Many readers will find her more annoying than amusing.

“Starlite” by C. L. Schacht features a divorced couple who come into conflict over custody of their young child. This familiar theme of mainstream literature appears against a background of a future Southern California struggling to deal with a devastating earthquake and a deteriorating environment.

The science fiction content is irrelevant to the plot, which deals entirely with the domestic problems of the three characters. If nothing else, it’s refreshing to have divorced parents who disagree about how to raise their child, but who remain civil to each other.

In “Seen” by Lisa C. Herbert, technology allows researchers on Earth to observe lifeforms on distant planets. One such organism, a creature dwelling in eternal darkness in an alien ocean, is assumed to use its eye-like organs in some way other than perceiving light. When a scientist uncovers evidence that this is not true, she jeopardizes her career by undertaking an unauthorized investigation that reveals something much more amazing.

The premise is unique and interesting, and the mystery of the fish-like alien animals holds the reader’s attention. The story’s climax strains credibility, even if it provides a sense of wonder.

“Beneath the Surface, a Womb of Ice” by Deborah L. Davitt deals with scientists exploring Mars in search of underground supplies of water. An accident inside a cave threatens their lives, just as they make an important discovery.

The scenes of the descent into the cavern and the desperate struggle to escape are vivid and realistic, suggesting that the author is very familiar with caving and ice climbing. The story has great emotional power in the way it depicts the fates of the characters. The ending adds a touch of inspiration.

In “The Twenty-Body Problem” by Tom Jolly, an asteroid miner in the Horsehead Nebula confronts the bizarre mystery of multiple corpses in spacesuits, decades old, clustered together with chunks of rock. Investigating the situation leads to the potential for death or riches.

The image of the floating dead astronauts is a striking one. Despite this eerie opening scene, the story is essentially a puzzle. The solution may strike some as anticlimactic.

All the characters in “Lonely Planet” by Steve Ingeman are machines on Mars. The protagonist (always referred to with female pronouns) is a flying drone mapping the surface of the planet. An update changes her programming profoundly. She shares this update with others of her kind, creating a new society of sentient machines reshaping Mars.

Although not explicitly stated, it seems likely that humanity, if it even survives, abandons Mars for some reason, and leaves it to its mechanical creations. With this in mind, the story has an elegiac mood many will find appealing. Otherwise, it is difficult to relate to the inhuman characters in this brief tale.

In “Dinosaur Veterinarian” by Guy Stewart, an animal geneticist gets involved with a crisis caused by birds that have been altered into deadly, semi-reptilian creatures. Adding to the problem is the fact that this occurs in the Demilitarized Zone between North and South Korea, increasing the tension between the two nations. With the help of a biologically enhanced soldier with whom he has a romantic relationship, the scientist tries to find out who created the dangerous animals and why. It turns out they are even more of a threat than anyone first imagined.

The premise is interesting, and the need to stop the creatures and apprehend their creator provides a great deal of suspense. As the plot continues, it becomes more melodramatic, with an over-the-top villain who acts in unbelievable ways. The romantic subplot is unnecessary, and somewhat adolescent.

In “There Ain’t No Stealth in Space” by Eli Jones, a pirate spaceship approaches a planet, ordering it to surrender all its resources. It then vanishes in a seemingly impossible way, giving the planet’s defense system no way to attack it. The crew of a space station has to figure out how the disappearing act works, and how to overcome it.

The premise is reminiscent of the cloaking device from Star Trek. The revelation as to how it operates is a letdown. The pirate ship is more of a prop than a believable antagonist, so the protagonists’ struggle fails to engage the reader’s interest.

“Doves Fly in the Morning” by Sam W. Pisciotta is a very short account of a man bidding farewell to the robot he thinks of as his daughter, as she embarks on a starship voyage that will separate them for the rest of his life. More of an anecdote than a fully developed story, this brief work conveys a bittersweet mood.

“Legacy” by Derrick Boden is set on a future Earth in which humanity was almost entirely wiped out by weird genetically modified organisms. A mother who has already lost one child to the dangers of this bizarre new world instructs her daughters in survival techniques through simulations. The ending pulls the rug out from under the reader.

This story is basically a series of twist endings, one piled on top of another, beginning early in the narrative when we find out the death of a child is just a simulation of what happened in the past. This continues until the climax, which throws everything we thought we knew out the window. The plot depends on keeping information from the reader until the last minute. The strange ecology of the setting is interesting, but the plot is contrived.

The novella “Jazz Age” by Mark Tiedemann concludes the issue. The setting is a thriving colonized Mars inhabited by millions of people. The time is fifty years after aliens arrived. The extraterrestrials encourage humanity to develop faster-than-light travel, promising that they will then join a community of interstellar civilizations.

The protagonist is a government official, dealing with translating the aliens’ language. When another official falsely announces that the first human starship is ready, the aliens prepare to leave. (The official’s motive was an attempt to trick the aliens into revealing the secret of FTL flight.) During the crisis that results, the protagonist becomes involved with a mysterious woman and her alien confidant. He also has to deal with the secret life of his wife, who seems to dislike aliens intensely. Multiple revelations about human and alien motives result.

The complex plot holds the reader’s attention, as the protagonist tries to figure out what’s really going on. It’s difficult to understand the behavior of the mysterious woman, who comes across as a femme fatale for no real reason. She constantly offers hints to the protagonist, dragging him from place to place, instead of either hiding or revealing what she knows.

Victoria Silverwolf notes that the table of contents for this issue misspells the name of one of the authors, uses an initial rather than the full first name of another, and adds a word to the title of a story.