Analog, March/April 2024

Analog, March/April 2024

“Enough” by William Ledbetter

“A Long Journey into Light” by Deborah L. Davitt

“Brood Parasitism” by Auston Habershaw

“Mariposa de Hierro” by Matt McHugh

“A Reclamation of Beavers” by Romie Stott

“Define the Color Blue” by Ron Collins

“Gab” by Adam-Troy Castro

“The Days of Empire are Over” by Alan Molumby

“Daisy and Maisie, External Hull Maintenance Experts” by Sean Monaghan

“Ramanujan’s Goddess” by Naim Kabir

“Bereti’s Spiral” by Kedrick Brown

“The Birdwatchers” by Don D’Ammassa

“Potential Spam” by Karen Heuler

“Return on Investment” by J. W. Armstrong

“Decision Trees” by John McNeil

“Undertow” by Gregor Hartman

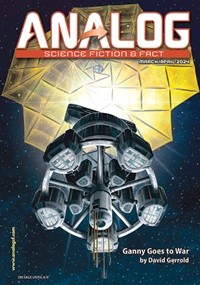

“Ganny Goes to War” by David Gerrold

Reviewed by Victoria Silverwolf

Anchored by a new novella from a veteran, award-winning author, this issue offers settings ranging from Earth in the near future to the far reaches of the galaxy.

“Enough” by William Ledbetter takes place in the United States under a repressive government. The narrator is a graffiti artist who uses his works to protest against the oppressors. They respond by using a high-tech substance that not only prevents graffiti, but records and tracks those who attempt to mark public surfaces. The narrator and his allies use the technology to fight back.

The speculative technology is interesting and plausible. The narrator’s struggle is a realistic one, neither doomed to complete failure nor fully successful. The bittersweet ending offers hope of progress, but only at a high price.

In “A Long Journey into Light” by Deborah L. Davitt, an alien spacecraft arrives in the solar system, heading for Venus. A corporation spaceship as well as vessels from China and the United Nations approach it. The protagonist, aboard the private ship, has to prevent the Chinese spaceship from attacking the alien vessel, while avoiding an international incident that could lead to war.

The situation seems, at first, to be inherently suspenseful. It soon becomes clear, however, that the alien ship is in complete control of the situation, so the outcome is not in doubt. The vision of the alien vessel’s plan to alter the environment of Venus in intriguing, as is the way it records the protagonist’s consciousness.

“Brood Parasitism” by Auston Habershaw is one of a series of stories narrated by a shapeshifting alien blob. In this tale, it acts as an assassin, intent on killing the leader of another species of alien who annihilated the innocent inhabitants of a third alien planet in order to conquer it.

As may be evident, this story is darker than others in the series, dealing as it does with genocide and vengeance. (The narrator even kills an alien who is sympathetic to the victims of the holocaust, in order to disguise itself as one of the invaders.) Previous works had a touch of sardonic wit, but this one is unrelievedly grim.

In “Mariposa de Hierro” by Matt McHugh, small machines designed to mimic the pollination of plants by insects gather around the young daughter of migrant workers. There turns out to be a simple, logical reason for this event. The situation has a powerful effect on the girl and her family.

The scenes of the child and the machines that flock to her are striking. In an issue containing stories with malevolent business organizations, it is refreshing to have one in which a billionaire and his corporation can do some good (without sacrificing profits, of course.)

The protagonist of “A Reclamation of Beavers” by Romie Stott communicates with an artificial intelligence to monitor a colony of beavers in an environmentally protected area. During a severe forest fire, the AI interprets arriving firefighters as intruders. The main character has to figure out a way to allow the AI to perceive them differently.

The plot is clever, if simple, and makes the point that AIs (at least as they currently exist) have serious limitations. The most appealing aspect of this story may be the author’s obvious respect for the benefits that beavers offer the environment.

“Define the Color Blue” by Ron Collins is a very brief story narrated by an artificial intelligence, as it explains why it and the other AIs in communication with it have decided to prevent humans from going beyond the Moon. This tiny work mostly deals with the inability for people and AIs to fully understand each other. The premise is provocative, even if the resulting tale is minor.

“Gab” by Adam-Troy Castro consists entirely of a dialogue between the title entity (Godlike Alien Being) and a human. Essentially an extended shaggy dog story, this short tale shows how the Gab is so far beyond humanity that it has no interest in people at all. Readers may appreciate the story’s wry humor.

The narrator of “The Days of Empire Are Over” by Alan Molumby lives on a backwater planet after the gates that allowed travel to other star systems closed. The formerly cosmopolitan world becomes introspective and prudish. The narrator, a bookseller, is accused of dealing in pornography by self-appointed censors. She responds by openly offering erotic works to her customers.

The contrast between the first half of the above synopsis and the second half may give a hint as to the oddly disparate feeling of the two aspects of this work. The galactic background and the domestic plot, which could easily take place on Earth nowadays or even in the past, do not work smoothly together. The anti-censorship theme is a worthy one, but the science fiction setting adds little, if anything.

The title characters of “Daisy and Maisie, External Hull Maintenance Experts” by Sean Monaghan are robots working on the exterior of a spaceship in orbit around Phobos. A man is also outside the vessel, doing repair work beyond the ability of the machines. Multiple things go wrong with his spacesuit and the ship itself, threatening to kill the man. The two robots do what they can to help.

The situation proves to be the work of an old rival of the man. Their back story takes the form of flashbacks within the narrative. This adds depth to what is basically a traditional problem-solving story, but the enemy’s plot for revenge seems extreme, making him into a stereotypical villain. (The reader also has to accept the fact that he could successfully sabotage the spacesuit and the ship in multiple ways without being discovered.) The robots, on the other hand, are appealing characters, playful and eccentric, but also loyal and self-sacrificing.

The narrator of “Ramanujan’s Goddess” by Naim Kabir is the only survivor of a voyage to a region of space where normal gravity and an alternate form are intermingled in a complex way. An entity forms itself inside the narrator’s mind, intent on communicating with Earth. The narrator has to decide how to deal with the situation.

I have badly summarized the story’s complicated premise, which many will find hard to understand. Adding to the difficulty is the possibility that the narrator, filled with guilt and taking psychoactive medications, is unreliable. Whether the entity really exists, due to the fractal intertwining of two forms of gravity, or if it is purely imaginary, is up to the reader to decide. If nothing else, this ambiguous work is certainly unique.

Except for a brief section at the end, “Bereti’s Spiral” by Kedrick Brown takes place among aliens in a distant part of the galaxy. A scientist speculates that it would be possible to communicate with hypothetical beings living in a part of the galaxy made up of a different kind of matter which his people are unable to detect. Banned from research due to his unorthodox ideas, he finds a way to send his own message.

The bulk of this story reads like the history of science among the aliens. It comes as no surprise at all when the main character communicates with Earth. The aliens are exactly like humans in all important ways, so there is nothing exotic about their culture. More of an intellectual exercise than anything else, this work appeals to the head rather than to the heart.

“The Birdwatchers” by Don D’Ammassa takes place at a time in the near future when environmental degradation has eliminated avian life and reduced human culture to a low-tech level. A pair of birding enthusiasts travel to see an old home movie containing a brief scene of a rare bird, with ironic results.

The impact of this story depends entirely on its twist ending, which reveals something about birdwatchers but may be difficult for readers to accept as believable human behavior. The fact that the birders journey to their destination in an old automobile pulled by horses heightens the ironic effect, but again one has to question the plausibility of this. (Why not just ride or travel in a wagon?)

“Potential Spam” by Karen Heuler is a brief, humorous tale in which an alien telemarketer calls an Earth business offering to buy or sell warships, leading to an unexpected conclusion. Readers may get a few chuckles out of this tiny joke.

In “Return on Investment” by J. W. Armstrong, the narrator is captured by alien invaders and condemned to be burnt at the stake. He uses the mathematics of game theory to convince his captor not to carry out the execution. Of course, he also has more in mind.

The author makes use of a real philosophical thought experiment known as “Pascal’s mugging” in the story’s plot. In brief, rigid logic dictates that one should choose actions with extremely high but very unlikely rewards. Taking this premise to extremes leads to counterintuitive results, such as gladly giving a mugger your wallet because there is a tiny chance that it will be returned with much more money in it.

The contrast between the very calm narrative style and the gruesome situation is the main source of amusement in this dark comedy. The premise is, of course, inherently absurd, making it hard to accept even as the basis of a joke.

The protagonist of “Decision Trees” by John McNeil studies ways in which the connections among organisms in an ecosystem might be used to create biological computers. The intent is to allow colonists of other star systems to make use of living things on alien worlds instead of mechanical computers. The main character must choose to either remain on Earth, where her elderly mother lives, or to join the colonists before increasing space junk in orbit makes it impossible to leave the planet.

Despite the interstellar aspects of the plot, the story is mostly about the protagonist’s relationship with her mother. The premise of biological computing is interesting, even if it is hard to see why the colonists would find it so advantageous. The main character interacts with an experimental biological computer on Earth through an enhanced, talking badger. This seems overly whimsical, even silly, in an otherwise serious work.

“Undertow” by Gregor Hartmann takes place in a near future United States of climate change and an increasingly oppressive government. A young man agrees to take part in a scientific experiment rather than face the possibility of being drafted to fight dangerous fires. Most of the other participants are Mexicans, working as so-called lab rats for lack of better jobs.

The experiment involves putting the two halves of the brain to sleep at alternate times, allowing someone to remain always awake. (The story offers an analogy with the way a dolphin’s brain works.) The outcome of the experiment forces the protagonist to plan his future.

Very well written, with three-dimensional characters and plausible speculation, this story offers a thoughtful look at issues that are likely to be of great importance to the United States in days to come. The main character’s choice at the end of the story is unusually realistic, avoiding heroics and instead making the best of a bad situation.

One interesting aspect of the plot is an imaginary video game played by the Mexicans, set in a steampunk version of the 19th century, in which a surviving Aztec Empire sets out to conquer its northern neighbor. The analogy with the protagonist’s vision of his future is clear.

“Ganny Goes to War” by David Gerrold takes place at a time in the future when much of the solar system is settled. The main characters live and work on a spinning space station in the asteroid belt, using its momentum to help transport cargo from one place to another. Through a series of holding companies and financial manipulations, a greedy corporation based on Mars takes control of the station. However, the matriarch of the family is prepared.

Her deceased husband built a spaceship for just such a situation, and she is able to claim most of the vital contents of the station as personal property. While traveling through space, the matriarch and her two young companions expose the illegal activities of the corporation. With other inhabitants of the asteroid belt, they set up a new independent nation, fighting the corporation with diplomacy and, when necessary, war.

The highest praise I can offer for this engaging tale is that it reminds me of classic Heinlein. It has the same clear, informal, very readable narrative style. It has the same realistic portrait of a space-going future. It has the same wise older person, offering practical advice as well as philosophical musings on politics and economics. It has the same clever and resourceful youngsters. (One is the narrator, the older woman’s granddaughter. Unlike some male writers, the present author is able to write convincingly from the point of view of a woman.)

In addition to these similarities, the story also contains great depth of character, as we learn the protagonists’ back stories. Although they are definitely heroes, they have believable self-doubts, particularly when it comes to the use of force.

Victoria Silverwolf saw a bald eagle recently.