Tangent Online Presents:

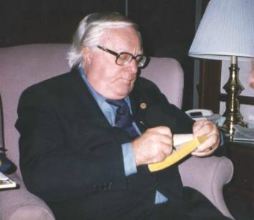

An Interview with Ray Bradbury

(1920-2012)

Interviewers:

Robert Jacobs, Dave Truesdale, Bob Wayne

Location:

University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh Radio/Television Department

(Telephone interview conducted early December 1975)

Interview originally appeared in Tangent #5, Summer 1976, and is reprinted here for the first time.

(Front and Rear cover art by Craig W. Anderson)

Introduction

Long-time Ray Bradbury friend Robert Jacobs worked in the Radio-Television department at the University of Wisconsin-Oshkosh, where I finished my final two years of college following a several year hiatus. I learned that Robert would be conducting another presentation of his traveling “Bob and Ray” show on campus radio soon, so I went to see Bob to ask if Tangent might submit questions for this telephone interview and then use the entire transcript in a forthcoming issue. With me present he proceeded to call Ray in Los Angeles. Ray readily agreed to everything and I even got to talk with him for a whole 45 seconds. Everything was set. Excited, I phoned fellow fanzine editor of Tales from Texas, Bob Wayne, and asked if he would like to submit questions I could ask Ray during the interview. Bob did so. As well, the following interview contains portions of an interview with Ray–also conducted by Robert Jacobs–which appeared in the February 1976 issue of Writer’s Digest, which Robert granted Tangent permission to use.

Therefore, the following interview consists of questions (the bulk of them) from Robert, Tangent, Bob Wayne, and portions of the Writer’s Digest interview. At this point in time I have no idea which questions came from whom, or which segments I took from the Writer’s Digest interview. I also don’t recall Bob Wayne’s Tales from Texas version of the Bradbury interview, and don’t think (but am not sure) he had access to the Writer’s Digest interview included in ours. I don’t remember if I transcribed the whole thing from tape, adding the WD segments, and then mailed them off to Bob, or just made a copy of the radio interview tape and mailed it to him. I just don’t remember.

This Bradbury interview, along with the Leigh Brackett & Edmond Hamilton interview included in this same issue of Tangent, are the two longest interviews I have ever done. Ray’s accomplishments are legion and he impacted the world of imaginative literature on a world-wide scale arguably more than any other author. For a fuller appreciation of his life and work I suggest starting with his wikipedia article.

Ray Bradbury was born August 22, 1920 in Waukegan, Illinois and died June 6, 2012 in Los Angeles, California. Much of Ray’s passion on a multitude of topics is captured in the following interview and I hope you enjoy it. It was a rare privilege to have been a part of it.

TANGENT: Ray, why did you go into science fiction?

RAY BRADBURY: Oh, it’s simply because I grew into it. When you grow up in the 20s the way my generation did, surrounded by Popular Mechanics and Science and Invention and The Boy Mechanic and things of that sort, and then radio coming into existence when I was two years old, and films began to speak when I was seven, and television on the verge of being invented and there was talk of space travel–it’s very exciting. And when you look at all of that…Buck Rogers hit me over the head when I was nine with the comic strips, and it was just kind of natural that I went mad and fell into the field. It’s really part of my entire nervous system. I can’t imagine living any other way.

Hey, I tell you, when you grow up in science fiction you grow up in everything! It’s the greatest and only field worth growing up in. It’s the total field. As a result of reading science fiction when I was eight, I grew up with an interest in music, architecture, city planning, transportation, politics, ethics, aesthetics on any level, art…it’s just total! It’s a complete commitment to the whole human race on all the Earth. That’s what science fiction is about. The irony is that it’s been made such fun of when it always has been the only relevant fiction that we ever had. It’s 10,000% more relevant when compared to the average American novel today, which is so “in” it’s out. The typical description on the flyleaf of the modern American novel reads, “A New York Jewish intellectual, aged 41, discovers that death means him and can’t decide whether to go back to his wife, his mistress, or his boyfriend.” That’s the plot and you say, “Oh, no, I don’t want to read that again! He’s going to do the Thomas Wolfe bit? He’s gonna discover life? He’s gonna go home again? He’s gonna find the ‘meaning of life’ and agonize and it’s gonna be the ‘Great American Novel’?”

You can’t try for that, you see? You must never name the goal. You must never tell us the target you’re hitting for. You must automatically go toward it without ever naming it. That’s true for all fiction. When you write a story and you want to show a man hating something, you don’t say, “He hated it.” You show him going through all the feelings that surround hatred; slamming doors and knocking books over and hitting children. But you never name the thing he’s doing. So, when you write the “Great American Novel,” hopefully to Jesus you won’t tell me you’re writing it!

TANGENT: There are a lot of critics today who say science fiction is kind of a narrow esoteric genre. Could you comment on that?

BRADBURY: Well, they haven’t been reading much, have they? They sound like a bunch of first graders to me. The mainstream fiction genre is the narrow one. It lacks, ideas, imagination, style, romance, and whatever you want to talk about is not in American mainstream writing today. All the kids nowadays are turning to science fiction because we have all the ideas that are effecting mankind. We were the first to write about ecology some forty years ago, and we didn’t even know it. People come along today and say, “Hey, The Martian Chronicles is an ecological novel,” and I look at it and say, “I’ll be damned, you’re right.” And that’s the best way to write; never self-consciously, never pontificatingly, never putting on airs. I don’t like the kind of writer who’s out to change the world and beat up on people for their own good. Stalin did that and Hitler did that, and to hell with them.

BRADBURY: Well, they haven’t been reading much, have they? They sound like a bunch of first graders to me. The mainstream fiction genre is the narrow one. It lacks, ideas, imagination, style, romance, and whatever you want to talk about is not in American mainstream writing today. All the kids nowadays are turning to science fiction because we have all the ideas that are effecting mankind. We were the first to write about ecology some forty years ago, and we didn’t even know it. People come along today and say, “Hey, The Martian Chronicles is an ecological novel,” and I look at it and say, “I’ll be damned, you’re right.” And that’s the best way to write; never self-consciously, never pontificatingly, never putting on airs. I don’t like the kind of writer who’s out to change the world and beat up on people for their own good. Stalin did that and Hitler did that, and to hell with them.

TANGENT: The term “speculative fiction” has been coined since so much of the current stuff has little to do with science and technology as such. Do you think the new term is more valid?

BRADBURY: It’s a good word. There are all kinds of terms. Call it what you want, but anything that even guesses ten minutes ahead or supposes new ways of birthing ourselves still fits. It’s fantastic to consider that there isn’t a major problem–in fact, I defy you to name a problem in the world at this very instant–that isn’t science fictional! Women’s Lib couldn’t exist without the effects of a science fictional device called The Pill. If you’d written about that thirty years ago, number one, you’d never have had them published, and number two, no one would believe them.

TANGENT: When you first started writing, one of the strict taboos in science fiction was even so much as a “damn” or a “hell,” much less any talk of the Pill or sex. Now we have science fiction stories dealing very frankly with sex, sexual problems, current social themes, and characters use all sorts of four-letter expletives when the story calls for them. What do you think of this “moral revolution” in literature?

BRADBURY: Well, that’s all come about through the change in the greater society. Most of it happened during the last six to eight years. Even pornography is a very necessary part of our lives. Now it’s come out in the open. Okay, maybe we’ve gone a little overboard here and there, but I think it’s mainly to the good. On the positive side of the ledger you have Man and Woman facing up to their sexual natures. I think it’s tremendously important. We have so much to give on the level of sheer lust and on the level of pure love.

We haven’t begun to talk about it yet. We just started the dialogue. In America we are such a frozen people in so many directions. We’ve been afraid to name our emotions, to name our loves. Men especially are afraid to cry. I’ve set a task for myself to teach men to cry and to laugh better and to create better and to love better. I can only see this as a huge improvement. We have to feel our way for awhile and then suddenly we’ll take a huge leap forward. We’ll dare to name our emotions to one another. Your friend will say, “Hey, has that happened to you?” And you’ll say, “Yeah, that’s happened to me.” “Well, do you ever cry in the shower?” “Yeah, it’s a great place to cry!” Well, once that’s out, you can get more men to crying and I think it’s only going to improve our culture.

TANGENT: That’s one thing Women’s Lib has going for it, don’t you think?

BRADBURY: Yeah. I argue with Women’s Lib about a lot of things, but this is one area in which I totally agree. They’d like to teach men to cry because in our culture we’re not supposed to. It’s not “manly.” Well, that’s a lot of crap! We’re identical to women, absolutely identical, in our need to release tensions. That’s why I write as I do. I’ve often been accused of being too emotional and sentimental, but I believe in honest sentiment, and the need to purge ourselves at certain times, which is ancient. Men would live at least five or six more years and not have ulcers if they could cry better. A woman can say to another woman, “I love you,” but it takes a long time for a man in a friendship to look at another man and say, “Hey, I love you.” Maybe never. Science fiction is deeply involved in these problems, too.

TANGENT: You have been classified as a science fiction writer, as you well know, and in fact some people have said you single-handedly elevated science fiction to a fine science and sort of got it legitimized. How do you feel about that?

BRADBURY: Well, there are a lot of other people in the field with me who have legitimized it. People like Arthur Clarke and Robert Heinlein around the world are very well known. I imagine if I had anything a trifle different to bring to it, it was my love and knowledge of theatre and poetry and the various other arts, which I imagine helps me do a kind of fiction that was a little bit unusual, a little bit different. And I imagine that has contributed a lot.

There’s plenty of room for competition here and it’s a very interesting family of writers. Heinlein was one of my teachers, Jack Williamson, Henry Kuttner, Ross Rocklynne, Leigh Brackett; the list is long and they’re all wonderful people, and all different. Now the great thing about our field is how different all of us can be. I’ve managed to get a little more attention than some but, on the other hand, at this very moment in time, Heinlein is doing very well in all the colleges of this country and many other countries.

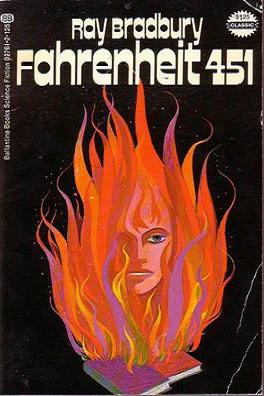

TANGENT: What did you think of Francois Truffaut’s film of your book Fahrenheit 451?

BRADBURY: It was a very good film, of course. The spirit of it is very close to my novel, and I’m very proud of Truffaut. I’m very happy with the film. The film has flaws, every film does, and I was very honest in talking with Truffaut at the time it came out–telling him where I thought there were some soft spots, or toward the end why I thought the chase didn’t work; it’s not exciting enough. You can’t get out of a major city as easily as Montag got out of that major city. It was all much too easy. And I imagine the reason that is true is they ran out of money making the film. And that can sometimes cut away all the things you intended to do, and you’ve spent all your money, and it comes on toward shooting the film in sequence; in this case it came on toward finishing it, and they simply didn’t have the money, which means buying time for themselves to do that properly. But the very end of the film is superb; the bookmen walking through the snow, remembering the books that they loved, acting out the books that they loved, being the books, with the snow falling all around them. That is one of the most beautiful scenes ever photographed.

TANGENT: Truffaut says that that was a happy accident, in fact. He had the crew out and it began snowing and they said, “Well, let’s pack it up.” And he said, “My God, no. Let’s shoot!”

TANGENT: Truffaut says that that was a happy accident, in fact. He had the crew out and it began snowing and they said, “Well, let’s pack it up.” And he said, “My God, no. Let’s shoot!”

BRADBURY: That’s right. They stayed, and as a result they have an ending there that puts it among, I would say, the ten top endings of any films of all time. You can name your favorite endings for pictures when you look back, can’t you? Sunset Boulevard for instance, the scene where Gloria Swanson comes down the stairs for her close-up and walks into the camera with Spanish music playing, and then the camera dissolves away and the film is done. Well, that’s one of the great endings. And then “Rosebud” at the end of Citizen Kane was one of the greatest endings ever. So, I put Truffaut’s ending right in that same category. It’s one of those things that carp as you may at the rest of the film, you look at that and say, Ahh, here’s a first class director who knows exactly what to do.

TANGENT: You had a somewhat altered experience when Rod Steiger played in the film of The Illustrated Man. What do you think about that?

BRADBURY: I had the feeling that nobody had bothered to read my stories. Which is a great shame. Because you know, I thought we had quite an affectionate relationship there. I was so delighted when they called me and told me that Rod Steiger and his wife were going to appear in the film, and on the basis of that I gave permission to buy up the rights and go ahead. Unfortunately, no one ever showed me the screenplay and when I finally did see it I realized we were in big trouble, and there wasn’t time to rewrite everything and, in fact, no one asked me to rewrite the screenplay. (Laughing) They thought they had a good script there.

BRADBURY: I had the feeling that nobody had bothered to read my stories. Which is a great shame. Because you know, I thought we had quite an affectionate relationship there. I was so delighted when they called me and told me that Rod Steiger and his wife were going to appear in the film, and on the basis of that I gave permission to buy up the rights and go ahead. Unfortunately, no one ever showed me the screenplay and when I finally did see it I realized we were in big trouble, and there wasn’t time to rewrite everything and, in fact, no one asked me to rewrite the screenplay. (Laughing) They thought they had a good script there.

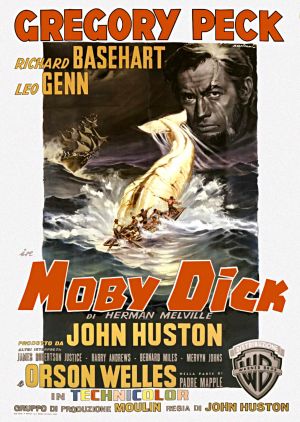

TANGENT: You have a great love and interest in films which not too many people are aware of. For instance, I don’t know that many people are aware that you wrote the screenplay for John Huston’s Moby Dick. How did you get into that?

BRADBURY: Well, I’d loved John Huston’s films for years. Back when I was 21 he made The Maltese Falcon. I think I saw it six times that first year, and fifteen or twenty times since. And then when Treasure of the Sierra Madres came out I rushed out to see that two or three times in the first week or so. So, my love for Huston goes back a long way, and when I’d published enough books of short stories I called my agent and said, “Now, I’ve got to meet John Huston,” because of all the people in the world I wanted to work for, it’s John Huston.

I met Huston and gave him my books and he went off to Africa to shoot The African Queen and I didn’t see him for two years. We corresponded very briefly and he said that he liked my books very much; someday we’d work together. He came back in August of 1953, called me to the hotel and put a drink in my hand and said how would you like to come live in Ireland and write Moby Dick. And that’s how I got the job.

(Laughing) John loved doing imitations of me when I heard the news. To his friends he would say, “And uh, Ray was sitting there, and uh, his jaw dropped and his breath went out of his body, and he fell over.” (Laughing heartily)

TANGENT: (Laughing) That’s a pretty good imitation of John Huston.

BRADBURY: Yeah, of John doing an imitation of me. So, it changed my life. It was one of the greatest things that ever happened to me, having Huston trust me, and want to work with me and give me that job, because ever after that I was offered all kinds of screenplays–that I didn’t accept. But nevertheless the offers were made.

BRADBURY: Yeah, of John doing an imitation of me. So, it changed my life. It was one of the greatest things that ever happened to me, having Huston trust me, and want to work with me and give me that job, because ever after that I was offered all kinds of screenplays–that I didn’t accept. But nevertheless the offers were made.

TANGENT: Huston’s quite a practical joker, isn’t he?

BRADBURY: Oh, very much so. In fact, when I was in the middle of writing the screenplay, I was around page 60 or so, a cablegram arrived which Huston handed to me and was from Jack Warner, head of Warner Bros. studios, and it said, “Absolutely refuse to proceed with filming of Moby Dick unless Bradbury writes large woman’s role into the film.” Well, I threw the cable on the floor and jumped around on it and swore–oh, terrible swearing–and in the middle of my frenzy I looked up and John was rolling on the floor, and of course he had sent the cable himself. So, that kind of joke I like very much. (Laughing) When I got over my rage it was beautiful.

TANGENT: As a result of living in Ireland during that time you wrote a series of plays based on The Anthem Sprinters. Would you like to tell a couple of Irish stories?

BRADBURY: Well, it was interesting when I was living in Dublin because I don’t drive. I had to hire a car every late afternoon and drive out through the fog and the mist and the rain with the sun going down at three o’clock in the afternoon–and people forget how far north Ireland is, how dreadful the winter’s are–and I’d do a scene from Moby Dick, finish the eight or nine pages, and hire a car and go out and visit Huston and generally have dinner there and come back home around midnight.

I would be driven by a fellow named Nick, from the local pub. I would call down to Heberson’s pub, Nick would come driving up to Terpcock there where Huston was living and we would drive back at a nice, easy, slow philosophical 32 miles per hour, along by the fields and past the farms and where all the priests of America are trained, and this went on for about 120 nights, and I got to know Nick very well, and I loved him because he drove nice and slow for old cowardly Ray.

So, it got on toward the first night of Lent and I said to Nick, “Nick, what are you giving up for Lent?” “Aw, yew know, it’s these things I’ve got in me mouth, they’re dire congestors of the lungs, it’s like gold fillin’s. I’m going to give up cigarettes for Lent, and God knows long after.” I said great, since I don’t smoke myself.

So the next night was the first night of Lent. I went out from Dublin, spent the night with Huston, and at the end of the evening we called down to Heberson’s pub, the old Irish driver showed up in his old 1928 Nash, and I got in and bang! We were off at 80, 85, 90, 95, a hundred miles an hour down the roads, racing, knocking roosters off the road, knocking priests and nuns sideways, racing through like a locomotive, and I looked over at my driver and said, “Nick, Nick, what’s that on your lower lip?” There was this cigarette on his lower face with this incredible fire and smoke filling the place, and he said, “Ah, God, I gave up the ither.” And I said, “The ither?” And he said, “The ither.” And I realized then for the first time in 120 nights that I was driving with a sober man. This monster! I thought I was driving with a human being and all of a sudden this monster takes over.

So, the next night when I came out of Huston’s I brought a bottle of the best with me and I handed it in through the window to Nick and said, “Now before we go anywhere, I don’t like that other person you’ve become, drink this.” And he said, “Oh, fer God sake, don’t tempt me.” And I said, “You’ll have to give up something else.” And he said, “In all of Ireland there’s nothing else to give up. Wait a minute…I’ll give up women.” I said, “Have you ever had any?” And he said, “No. But I’ll give’em up anyway.” (Ray, chuckling profusely) And he drank this stuff down, and his face mellowed and his hands softened on the wheel. I looked at him then, and said, “Oh, Nick, Nick, you’re back!” And he says kinda shyly, “I was long away.” So we drove into Dublin at a nice, steady 32 miles per hour.

That’s a true story, and it happened to me, and I wrote it. It’s part of my Anthem Sprinters collection.

TANGENT: You’ve written about all kinds of marvelous machineries, including one which took Ernest Hemingway from the place where he shouldn’t have died and put him back where he should have. You’ve written about rocketships and airplanes. Is it true that you do not drive and do not fly in aircraft?

BRADBURY: No, I’ve never learned to drive and I’ve never been up in an airplane. The nearest I’ve been to that is going up in the Goodyear blimp and chasing whales along the California coast. Which was just great, that was just beautiful. I love blimps and balloons because when you cut the motor on a plane you’re in big trouble (chuckling). So, I would love…wouldn’t it be great…to go cross-country in the Goodyear blimp and write a record of your landings in farm fields, and meadows, and just going across the country at that nice leisurely pace. I think that would just be jolly.

TANGENT: But when you go from here to England you just take the train and then the boat, right?

BRADBURY: Yeah, right.

TANGENT: What is it about cars?

BRADBURY: Oh, I don’t know. I think I’d be a lousy driver, a murderous driver the way most drivers are, and a danger to themselves and others and most people don’t have enough courage to know this about themselves. And then I imagine…because I saw so many people hurt and killed on my way back and forth across the country when I was 12 and 14 years old, with my parents. When you see enough of that kind of murder I think it fills you up and you don’t get over it–at least I never got over it. So, I decided not to be part of that.

TANGENT: We were talking about films earlier. Fahrenheit 451 ran on a double bill up here with 2001: A Space Odyssey, or Oddity, as you will, and as you know Space Odyssey has sort of caught on and become a cult film, like 451 seems to be doing now. What do you feel about 2001?

BRADBURY: It’s the single most beautiful film ever made. You look at it technically and photographically… I saw it again the other night at Filmex Screenings where we put on a fifty hour marathon of science fiction films, and I hadn’t seen it in a couple of years, and of course every time I see it I’m just astounded at the technical facility of this film and the entire look of it. The camera work is absolutely incredible. But when you’ve said that, you’ve almost said the whole thing. You know, it’s in very bad taste for one writer to speak of another writer, but in this case I’m not really talking about Arthur Clarke, I’m talking about Kubrick who directed the film and who also, I think, ruined the script. Every time I look at the film I get furious at their inability to handle all this beautiful equipment better. You know, they turned the astronauts into such bores. Well, astronauts are not bores. I’ve spent enough time with them to know they’re not boring people. I spent an afternoon with Buzz Aldrin about ten days ago, the first time I really had a chance to sit down with him and talk, and we were talking philosophy and politics and children’s books and you name it. But he’s not like any of these people we saw in 2001, nor are any of the other astronauts I’ve met. People like John Glenn, Mr. Grissom, Mr. White, and Mr. Chaffe. I met those last three men about ten days before they were killed in that fire.

So, when I see this film I say wait a minute, this is ridiculous that they didn’t do more with the characters or the people. They missed a real chance there.

TANGENT: They missed the whole humanity of the thing.

BRADBURY: Yeah, right.

TANGENT: What inspired you to write Fahrenheit 451?

BRADBURY: Well, that all came about during the Joseph McCarthy era, in the period of McCarthyism when the country was going a little crazy and allowing itself to be terrified by that dreadful man. And we had a lot of chickeny people around who didn’t do anything, including a lot of our great democratic liberals who never spoke up. Everybody sort of sat around and let McCarthy throw his weight around and nobody was brave. So I got angry at the whole thing and said to myself that I didn’t approve of book burning; I didn’t approve of it when Hitler did it, so why should I be threatened about it by McCarthy? Because he was beginning to threaten things like our overseas libraries, and certain things shouldn’t appear on the library shelves. Well, that’s nonsense. So in a rage I wrote a 25,000 word variation of Fahrenheit and then later added another 25,000 words, and, by gosh, the book was published and has done very well, and I think the reason the book is so popular is that it makes its points about pontificating without being too self-conscious, without preaching to people, and I think that’s the most important thing. It’s an adventure story that happens to be about an important issue.

BRADBURY: Well, that all came about during the Joseph McCarthy era, in the period of McCarthyism when the country was going a little crazy and allowing itself to be terrified by that dreadful man. And we had a lot of chickeny people around who didn’t do anything, including a lot of our great democratic liberals who never spoke up. Everybody sort of sat around and let McCarthy throw his weight around and nobody was brave. So I got angry at the whole thing and said to myself that I didn’t approve of book burning; I didn’t approve of it when Hitler did it, so why should I be threatened about it by McCarthy? Because he was beginning to threaten things like our overseas libraries, and certain things shouldn’t appear on the library shelves. Well, that’s nonsense. So in a rage I wrote a 25,000 word variation of Fahrenheit and then later added another 25,000 words, and, by gosh, the book was published and has done very well, and I think the reason the book is so popular is that it makes its points about pontificating without being too self-conscious, without preaching to people, and I think that’s the most important thing. It’s an adventure story that happens to be about an important issue.

TANGENT: You seem to be terribly involved about important issues all the time in your writing. For instance, right now you’re very concerned about cities, and what’s happening to them, and many of these considerations are beginning to take place in your stories. Tell us about cities, Ray.

BRADBURY: When you look around at some of the new developments, the architecture of so many of our cities is so dreadful, and they sort of plan people out of existence. There’s no place to sit down, there’s no place to eat outdoors, all the things that make living–especially in California–so beautiful, are being ignored here in L. A. and in other towns. So what I’m trying to do is encourage the City Fathers to use more imaginative thinking in their architecture, in their city-planning, in their rapid transit; excite them to the potential of these things, and a number of cities have begun to call on me to come in and criticize their plans. Well, I’m not really a planner, I’m not an architect, but I do have a sense of what looks good I think, what is agreeable, what is social. And so I’ve been out to Pasadena, to Pomona and Orange in the last year just to visit the mayors and the City Fathers, planners, and congratulate them when a thing looks good, and demure when a thing isn’t quite right.

This happened down at Century City here a couple of years ago. They called and said how would you like to help us do a tape-recording of your feelings on Century City. I said I’ll certainly do it if you publish everything I say. And they agreed, and of course I just took the place apart, and again because they didn’t make enough plans, in a spacious city like this, for places to sit and enjoy people. You could have lots and lots of restaurants outdoors, protected from the wind–there’s lots of ways of doing that. And I’ve been over there several times in the last week and I don’t see any signs of their planning for people much. The city falls into two sections, and there’s no way to get from one section to the other without crossing a huge boulevard. And this most people won’t do, so the two cities are truncated and there’s not going to be any cross-pollination between the two sides. Which is most unfortunate.

TANGENT: We have a lot of interest now–as you’re perfectly aware–I’ve read articles of yours commenting on it, about preservation of our environment. We’re suddenly aware of it. Do you feel optimistic about it?

BRADBURY: Oh, yes. Millions and millions of people are involved in various movements now like Ralph Nader and Common Cause which are beautiful groups. Jacques Cousteau has started a new group which I hope to join in the next week or so, to protect the sea environment. Many of the big corporations are discovering it’s good business, it’s good public relations, and it’s good humanity to participate in all this. Standard Oil I think, reinstituted funds for a game preserve up around San Francisco about a year ago, as a result of pressure being put on them. Well, that’s great, and as soon as they do something like this we have to congratulate them. We have to remember that corporate heads have to go home each night and sit with their children at dinner, hmm? And so we should learn to praise more often as well as criticize when someone does something right. So I’m trying to teach people of all ages to, number one: how to criticize, how to offer creative analysis on top of that, how to try to build things in a new direction and how to compliment people when the thing gets done.

I helped to put together a propaganda campaign for a library down in Huntington Beach three or four years ago and I wanted to speak to the City Fathers and the whole community and say for goodness sakes, if you’re willing to build a library, why not make it more than that, why not make it a real social center because we all love libraries to begin with, and use them as social centers as we grow up. Many of us do. And give us more than one reason to go to a library, why not? Good classic films maybe run there every Monday night, lectures one or two nights a week in a special room, art exhibits in another room, or a combination of those. So by gosh, the library is finally built down in Huntington Beach, and opened, and I haven’t had a chance to get down and see it but I’ve seen photographs and it looks terrific. And it’s this sort of thing I’m interested in doing; encouraging people as well as criticizing them. And once in awhile when you see something happen it does make you optimistic, and more and more things are happening in these fields.

TANGENT: Many times these days people say nobody’s reading anymore, nobody’s publishing anymore, a new writer can’t get started. How do you feel about that?

BRADBURY: No. It’s just not true. That’s one of those intellectual clichés. If you go to the local bookstore you’ll find that that’s not true at all. New authors are being published every single day of the year, and if you’re talented people will discover you. We all have to start somewhere, and remember there was a time, 28 years ago, when I wasn’t being published in anything, and gradually I began to move into more and more magazines. I was my own agent. I didn’t have an agent to help me with a lot of my early sales, especially in the quality magazines. So I just sent the things out myself and I sold a story to Collier’s on my own. I sold one to Mademoiselle and I sold one to Charm, completely on my own with no name, no reputation, no agent, living in Venice, California making $40 a week at writing when I was lucky. The last several years have been some of the best years for book sales that I can remember. The sale of books is still very high. There are several thousand new fiction titles every year and the last figures I saw seem to indicate to me that the bookstores are still doing very well.

And it’s not true that people are not reading. The libraries are doing very well, people are going to the libraries, people are borrowing books. It would be interesting to do a little real research for those people who say people are not reading anymore. Just go and do some real research and see how much your local library was being used last year as opposed to say five or ten years ago. I think you might be surprised at the results.

TANGENT: You said something once about helping people get through the night. And many of your stories, as in Dark Carnival, deal heavily with death, terror, and horror. Why do you deal with such terrible, scary stories?

BRADBURY: Well, if you love people you criticize them, and if you don’t love them you don’t criticize them, you let them go to hell, don’t you? To help any kind of friendship, your marriage, your children, you criticize because you love. And this works the same way. With your friends–let’s say in writing–if you don’t offer criticism to them and scare them on occasion… In other words you say to a new writer, for gods sake write, because if you don’t you will disappear. The world doesn’t give a damn about you unless you do something. Those are the rules; I didn’t make them. If you are lazy, if you don’t get the work that you love done, the world won’t care if you die tomorrow and go into the grave and are gone and forgotten forever.

BRADBURY: Well, if you love people you criticize them, and if you don’t love them you don’t criticize them, you let them go to hell, don’t you? To help any kind of friendship, your marriage, your children, you criticize because you love. And this works the same way. With your friends–let’s say in writing–if you don’t offer criticism to them and scare them on occasion… In other words you say to a new writer, for gods sake write, because if you don’t you will disappear. The world doesn’t give a damn about you unless you do something. Those are the rules; I didn’t make them. If you are lazy, if you don’t get the work that you love done, the world won’t care if you die tomorrow and go into the grave and are gone and forgotten forever.

No I intend to frighten my friends with that on occasion; to get them to write a song, a play, do a poem, write a short story, paint a picture, no matter what it is, to scare the hell out of them and get them to realize that tomorrow is coming on very fast and soon enough most of us will be dead, period.

So get your work done. And I also do this in stories, but not as a social reformer. Just to show them that I have passions, and these things scare me, too. So I figure…I hate book burners, I hate’em with all my heart. I hated Hitler and what he did to his country. I hated Stalin and his book burners. I hate what goes on in China with all the book burning. And if I care enough then I write a novel called Fahrenheit 451, and I say to Montag, “Montag, run ahead of me, write this novel for me, teach me how not to burn books.” Nine days later Montag finishes writing the book for me; he is my passionate character in search of himself. That’s the way you write a book. But not as a way to tell the world how to behave. If you’re a passionate person afraid, then you can start to instruct the world.

TANGENT: When you’re writing, do you see things happening?

BRADBURY: Absolutely. You have to live in a cloud of emotions. You rev yourself up. Give yourself time in the middle of the afternoon, or when you’re waking up early in the morning, when you’re in that kind of wonderful, euphoric state in-between, on the verge of dreams when you get a kind of nuclear bombardment of all kinds of fragments of ideas jumping around inside your head and hitting each other. They begin to fuse and detonate each other. It’s a very hard thing to describe. You don’t have any control over your mind at a time like that, and you don’t want it, see? Let it run wild! Then watch it remotely at the bottom of your skull. Look up at all those things running around wild, then jump up and run over to the typewriter and feed them in!

TANGENT: And don’t think about them, eh?

BRADBURY: No! You cannot write by thinking. You have plenty of time to think in between times. The period in between is when you stuff your eyeballs, when you read diversified multitudes of material in every field. I absolutely demand of you and everyone I know that they be widely read in every damn field there is: in every religion and every art form and don’t tell me you haven’t got time! There’s plenty of time. You need all of these cross-references. You never know when your head is going to use this fuel, this food for its purposes. Stuff yourself with serious subjects, with comic strips and motion pictures and radio and music; with symphonies, with rock, with everything! What we often forget is that thought is to be used to correct life. It’s not a way of life! If you make thought the center of your life, you’re not going to live it. So, what you have to do is be this kind of hysterical, emotional, vibrant creature who lives at the top of his lings for a lifetime and then corrects around the edges so that he doesn’t go insane or drive his friends mad. Thought is the skin around the organ. The organ is full of blood and a beating heart, a soul and the exhaltation of being alive!

TANGENT: Ray, you have a fascinating story called “The Small Assassin.” It’s about a six-month old baby who murders his mother and father. Tell us about this.

BRADBURY: Well, this was the result of my own background. I can remember the moment of my own birth, and just about everything since.

TANGENT: You can remember being born?

BRADBURY: Yes, right. I first began thinking about this quite a bit when my first child was born about 26 years ago. We came home from the hospital, had been home a couple of nights, and my daughter Susan had nightmares in her crib. We checked to see if she was dry or hungry or a pin was sticking her, and that was not the case; she was having a nightmare. Well, how can a child who is only three or four days old have a nightmare? Well, the only thing it could be about was being born; that’s the only memory they have, it’s the only big event and it’s a super event in your life, isn’t it? The big thing of being born. And the next big ones after that are sex, passion, lust, love…and the next big trauma is growing old, then sickness, and then death. We all have four or five traumas to go through.

Looking at my childhood from the crib I remembered having a nightmare in my crib when I was four or five days old, and they continued for about the first year and I’d wake up having a nightmare of being born. I asked my mother when she stopped nursing me and she said when I was three days old. Well, I remember the flavor, the camera angle, everything. I asked her how old I was when I was circumcised, and she told me three days old. And I told her, it wasn’t in a hospital, was it? And she said no, why do you say that? And I told her because I have a memory of a place much like and office and somebody bending over me with a scalpel, and the pain. She said, my god, it was the third day you were born, and it was in the doctor’s office that I had been taken to be circumcised. So, it’s interesting to have all these memories of suckling, being circumcised, being in the crib.

TANGENT: How do you tie all this in, Ray, with loving and being kind, when you have a six-month old baby as in “The Small Assassin” who kills his mother and father?

BRADBURY: You must remember this: every single story you do in your life is not all part of the same thing, is it? You don’t write the same kind of story over and over again; you write all kinds of stories. You write stories of murder because we want to kill people. It’s the reverse of love and this is part of the dichotomy, or paradox, of being human. Unless we can accept the fact that we have love-hate relationships quite often, our friends, our lovers, our mothers and fathers–then we’ll never be human. If we try to deny the darkness in our souls then we’ll become completely dark. This was Hitler’s gift to the world. Hitler, and in effect, Stalin, Mussolini, Lenin, and Chairman Mao, too, and all these other monsters, are capable of saying, “I’m a perfect human being. I love only, and do not destroy.” Well, as soon as you say that then you can destroy anyone, because you’re the good guy, it’s okay to kill anyone that you want to kill. But of course this isn’t true. The Greek philosophies teach us that we are a combination of dark and light, good and evil, and murderer and savior, hmm? And until we know this completely about ourselves we cannot love well, and we cannot forgive ourselves.

BRADBURY: You must remember this: every single story you do in your life is not all part of the same thing, is it? You don’t write the same kind of story over and over again; you write all kinds of stories. You write stories of murder because we want to kill people. It’s the reverse of love and this is part of the dichotomy, or paradox, of being human. Unless we can accept the fact that we have love-hate relationships quite often, our friends, our lovers, our mothers and fathers–then we’ll never be human. If we try to deny the darkness in our souls then we’ll become completely dark. This was Hitler’s gift to the world. Hitler, and in effect, Stalin, Mussolini, Lenin, and Chairman Mao, too, and all these other monsters, are capable of saying, “I’m a perfect human being. I love only, and do not destroy.” Well, as soon as you say that then you can destroy anyone, because you’re the good guy, it’s okay to kill anyone that you want to kill. But of course this isn’t true. The Greek philosophies teach us that we are a combination of dark and light, good and evil, and murderer and savior, hmm? And until we know this completely about ourselves we cannot love well, and we cannot forgive ourselves.

Well, “The Small Assassin” is a way of understanding the destructive principle in any child. Any child, at some time or another, has had thoughts of murdering their mother and father…like my story “The Veldt.” Every child who reads this, where lions come out of the walls of the room, in order to devour the parents, all the kids go “Whoopee! Hurray! I know that.” Now, if you’re not careful you can make them feel guilty for thinking that. You mustn’t make them think that because we’ve all wanted to kill–in that moment of love–the person that we love. It’s part of the human mechanism. Why the mechanism works the way it does is a mystery to us; we can’t expect anything to perfect.

If you have a friend that you love very much you feel they know too much about you, you’ve exposed yourself to that love, you’ve stuck your neck out, you’ve revealed yourself completely. They know everything about you, and if they wanted to, they could tell the world all your weaknesses. That’s the part where the murderous impulses come from. And that doesn’t mean that you go out and do it, but we must be comfortable with this impulse so we won’t go out and murder.

TANGENT: A lot of people feel there is too much violence on TV today. How do you feel about this?

TANGENT: A lot of people feel there is too much violence on TV today. How do you feel about this?

BRADBURY: As long as it isn’t repetitive and too sick. There is a kind of violence at times that is so inordinate that it is sick. I mean the Manson family, for instance; that is so incredibly sick, just incredibly so. Well, there are certain things you can’t go into because they’re so beyond the pale. Murdering children, or murdering a pregnant woman and then tearing the body is so beyond our thinking as to be unimaginable, you can’t imagine it. Well, that’s what they did. Horrible, these people are. So, we can’t even talk about it.

But, ordinary violence, which comes in the way of comparing good and evil, helps to exorcize those spirits within ourselves which need to be exorcized. In other words, the will towards violence is there, and if we don’t get rid of it in one way or the other…either directly by hitting someone, which we don’t want to do…or we try to build ourselves a society here set up with laws made up to try and control ourselves, because we know we have a will toward violence. Now, we have to live within those laws if we want to build cities and raise our children and grow old in peace. But in truth, where does the violence go? So, all of this being true, our arts must help us to free the violence that is in our soul. Now, I don’t know what all of the rules of the game are, but if our movies and our televisions don’t have a certain amount of this we will become a society bound completely by laws, so the anarchy that rages within us on occasion will burst out and be ten times worse. So, if we need these steam valves to let some of this out of us occasionally–and we have to look at this very carefully–to find the right proportion for our children, and for ourselves. Somehow we’ve got to find the right proportion if we want to build a society that allows itself to vent its rages, so that we don’t have to go outside the law for it.

You tell me what the proportion is, I’m not quite sure.

TANGENT: One thing that strings through all of your writing–all of your writing is very personal and very individual–your fiction is filled with memorable individuals. What would you care to say about individualism as opposed to the professional joiner, the group person, and so on?

BRADBURY: We have to encourage combinations of things. We can’t live alone in any society. But the best way to help a society or group, is to be the best individual in it that we can be. I’m willing to help people, I’m willing to help groups…but the best way that they can enable me to help is by letting me be myself. I can only speak for myself, and at the top of my creativity I can move into any group and prove it simply by being myself, by giving input that counts. By being critical at the right moment, by being constructive, by being honest. Not pulling things down to pull them down, but at the moment of criticism to offer construction. I think it’s got to be a combination. In any society there has to be a combination of individuals working at the top of their passion, their love and dedication, and their talent. Plus a group who comes up under them or with them and implements that thing. There are many areas where we can work alone, other areas where we need other people to cooperate with us. And a good society should offer the alternatives, shouldn’t it? And that’s what’s great about America today. There’s a combination of this. Very few countries in the world offer this kind of opportunity, not only for working in groups, but working as individuals. This is maybe the only country where it functions first class.

TANGENT: In your introduction to the second volume of the collections of the EC stories, Tomorrow Midnight it was called, you stated that you’d like to be able to write your own Sunday comics page. Ten years after writing that introduction, would you still like to do something along those lines?

BRADBURY: Oh, yes! I’ve grown up with a huge love of comic strips and comic pages and the Sunday papers. In fact I used to get–we were a very poor family and we couldn’t afford to buy all the Sunday papers that we wanted to buy, including The Milwaukee Journal. The Milwaukee Journal used to have full-page spreads of Tarzan; on every Sunday it was just gorgeous, but we didn’t have a chance to get all of them because they were too expensive. So, my early influences are Tarzan in the Sunday papers, and Buck Rogers in a Boston newspaper, and collecting all different comic strips starting when I was nine. I have all the early Flash Gordon Sunday papers put away.

And out of this love it’s fascinating to see, later in my life, when the Buck Rogers people did the Collected Works of Buck Rogers, they came to me to write the introduction to the book. And the same thing with the latest book on Edgar Rice Burroughs that came out to celebrate the 100th anniversary of his birth. They came to me for an introduction, and isn’t it beautiful that the nine year old boy who fell in love with Buck Rogers and Tarzan, so late in time, is being asked by the relatives and heirs of these influences to come and help out. And…it’s a good way to live, isn’t it?

TANGENT: (Question from listener) What do you think of Star Trek?

BRADBURY: For the most part it was about tits and not ideas, and if the women’s libbers don’t like it to hell with them. The women had a multitude of tits and no brains.

TANGENT: Would you write a script for Star Trek if they asked you, now that there are plans to revive it?

TANGENT: Would you write a script for Star Trek if they asked you, now that there are plans to revive it?

BRADBURY: If they asked me I would…but I don’t think they’d ask me (chuckling). I think they’re afraid of me. They’ve got some idea that I’m in league with Satan or I’m a Martian or something–a real one! First of all, it’s very hard to write about characters that are not my own. I’d like to but I don’t think it would work out.

TANGENT: Ray, we’ve been talking about things happening recently. What do you think of the recent occurrences in the Northwest where people have been selling all their belongings, their homes, possessions, so that these “people from outer space” can take them to a better world?

BRADBURY: It sounds like areligious flim-flam, doesn’t it? That’s my opinion of the whole damn thing. I think it was one of the famous New York intellectuals in the late 20s who said, “When you think of all the suckers out there in wait for you…” And it makes a con-man just tickle all over, with all those suckers out there just waiting to be taken.

So, these people are all suckers. If I wanted to change my profession tomorrow I could go into ESP; I could ride a chariot of the gods across the country wearing my robes pulled up (laughing). I could start in L. A. with a team of horses and by the time I got to Milwaukee I’d be rich!

TANGENT: You’d also look good in a toga.

BRADBURY: Oh, yes (laughing)…I’ve got great legs!

TANGENT: What memories do you have of producing your own fanzine, Futuria Fantasia?

BRADBURY: That was during my last year in high school when I was 17 and 18 years old. I grew up with Forrest J Ackerman who is now editor of Monsters of Filmland, and at that time I had no money. Of course I couldn’t afford to put out a magazine, so I think Forry shelled out 40 or 50 or $60 per issue, about four times a year, to enable me to be an editor. So, this is a wonderful man who’s been a part of my life since I was a kid and by god, people like Heinlein, and Henry Kuttner and others I got to write for the magazine, back in 1938. And I was very lucky to be living in L. A. then, and attending meetings in a cafeteria of all places, and we’d meet every Thursday night, upstairs in this little cafeteria, with all the big names in science fiction: Jack Williamson, Edmond Hamilton, Leigh Brackett, A. E. van Vogt. At one time or another everyone’s name who is familiar to you now, was there at our meetings, and I became a student of these people, I became a disciple of these people and I got them to work for my magazine. And gosh, you look at that magazine today and you’d never predict that that boy would ever do anything you’d want to read.

BRADBURY: That was during my last year in high school when I was 17 and 18 years old. I grew up with Forrest J Ackerman who is now editor of Monsters of Filmland, and at that time I had no money. Of course I couldn’t afford to put out a magazine, so I think Forry shelled out 40 or 50 or $60 per issue, about four times a year, to enable me to be an editor. So, this is a wonderful man who’s been a part of my life since I was a kid and by god, people like Heinlein, and Henry Kuttner and others I got to write for the magazine, back in 1938. And I was very lucky to be living in L. A. then, and attending meetings in a cafeteria of all places, and we’d meet every Thursday night, upstairs in this little cafeteria, with all the big names in science fiction: Jack Williamson, Edmond Hamilton, Leigh Brackett, A. E. van Vogt. At one time or another everyone’s name who is familiar to you now, was there at our meetings, and I became a student of these people, I became a disciple of these people and I got them to work for my magazine. And gosh, you look at that magazine today and you’d never predict that that boy would ever do anything you’d want to read.

TANGENT: Are you aware that a dealer has offered to sell a set of issues 2-4 for $200?

BRADBURY: Oh, my god! No, I never dreamt that sort of thing would ever happen.

TANGENT: What influence did Henry Kuttner have on you as a writer?

BRADBURY: Well, he was a friend and part of that group, too. He was a member of the Science Fantasy Society. He was working for a literary agency at the time and he said, “If you have any short stories I’d be glad to read them.” So, he read a lot of my things, but the best advice he gave me was when Iwas around 21 years old. He came up to me and he said, “Ray, do you wanna do me a favor?” And I said, “What?” He said, “Shuddup!” I said, “What?!” And he said, “Shuddup! You go around telling your ideas to people, you grab them by the lapels, shout in their ear, and you mustn’t give it away! You mustn’t give away your passion. Go put it in a story. Don’t tell your ideas to anyone and go write the stories and I’ll read them.”

And so, since 1941 I’ve never told anybody about anything I’m working on. You keep it inside yourself. If you’re a writer for god’s sake shut up and go write it, and when you finish the thing then go show it to someone and talk about it. But when you talk about it ahead of time it’s like throwing sense out the window; forget it. Do it, don’t talk about it. In thought is nothing, in action is everything.

TANGENT: What part, if any, since you are politically active, did you take in the movement to dump LBJ?

BRADBURY: That’s a very good question because I hated that son-of-a-bitch. He was one of those door-to-door tie salesmen. LBJ was that kind of son-of-a-bitch. He bragged a lot about his bloodline and he turned out to be a bastard. I watched his policies in Vietnam; he sent in 500,000 troops, all behind our back. All lies. He was a far more reprehensible criminal than Nixon wil lever be because Nixon didn’t send 500,000 troops in. But old LBJ did. He was a great liberal that I voted for (chuckling). So I said goddamn, what can I do? Do I believe in the American system? Yes, I do. So, there was this group that came along, the Southern Democrats, and they said, “Hey, will you help us?” And I said, “Sure will.” A copy of the ad, strangely enough, is right here on my desk. It was an ad that was going to be in the L. A. papers on the day LBJ was going to be in town, and it said something to the effect that we are 5,000 Democrats who voted for you and are now completely disassociating ourselves from you because of your conduct in the Vietnam War.

And all my friends said, don’t do this, LBJ won’t step down. And I said, yes he will, I believe in the American system. And sure enough, he did. He didn’t run for re-election.

TANGENT: Would you care to tell us the story and love you felt for Ernest Hemingway? I believe the story you wrote about him was one of the two pieces of fiction LIFE magazine ever published.

BRADBURY: Well, of course, I was dreadfully upset at his death fifteen years ago, his suicide, and of course a lot of people didn’t realize what happened to him, what happened to Hemingway. But back in January or February of 1954 he was in two consecutive airplane accidents, one day following the other. And after the first accident there were a few headlines around the world saying, “Hemingway Killed in Africa.” Well, a few hours later that story was retracted and they discovered he’d walked away from the airplane. And he found another airplane the next day and he got in it and it crashed. Well, the second crash hurt his body terribly, and physically he never got over the trauma of that second accident.

Ideally, what should have happened is that he should have been killed in that second accident, because I feel that’s what most of us would want, or he should have walked away in better shape; we don’t wish torture on anyone, the kind of agony that goes with a bad accident goes on for years and years.

So, when he killed himself that was traumatic to me, it hurt me terribly and I worried about it. So, one night I’d been out with my wife and we were driving home…and something about being in the car and something about talking about something about Hemingway and I suddenly got this idea and I said, “Get me home, because I think I’ve figured out a way to save Papa.” My wife didn’t know what I was talking about. I got home, ran down to the basement and got to the typewriter, and that night and the following morning I wrote this “Kilimanjaro Device” story, which is merely a story of a lot of people touching a safari-trek car with their love, their feeling, their dedication for Hemingway’s stories, and places, and times. And then I go off as the leading advocate of that love to find Hemingway on the highways of Idaho. When he was alive he used to walk along this particular road. So I take the safari-trek car and hope that by some miracle I can go back in time and drive along that road and maybe find Papa. And by gosh, I do, by this miracle of love this safari-trek car goes back along the road and I see this old man walking along with this beard and steel-rimmed glasses and I say, “Papa?” and he turns and comes up and says, “Yes,” and I offer him a ride back in time and at the very end of the story I know that this safari-trek car will turn into an airplane, and at the proper time we will crash and that Hemingway will be killed in Africa, that his body will be put up on the slopes of Kilimanjaro and buried there where he belongs.

I wrote the story and it was rejected by many magazines, and then I got the idea of sending it to LIFE, and they bought it within 48 hours and they published it. The greatest tribute that I’ve ever had was getting in the mail, letters from all over the world saying, “Thanks…for getting Papa off the road.” So, there, I proved my love, didn’t I.

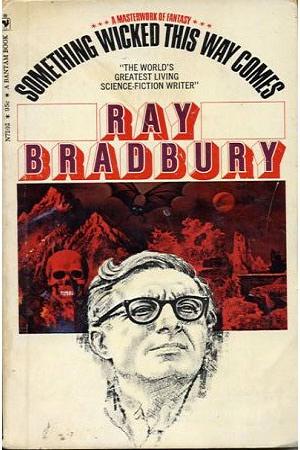

TANGENT: One more question, Ray. You wrote a very beautiful book called Something Wicked This Way Comes, which many people say is the scariest book they’ve ever read. What is Something Wicked This Way Comes all about?

TANGENT: One more question, Ray. You wrote a very beautiful book called Something Wicked This Way Comes, which many people say is the scariest book they’ve ever read. What is Something Wicked This Way Comes all about?

BRADBURY: Well, first of all I was born in Waukegan, Illinois. We used to drive up to Oshkosh on occasion, to Madison, in the summertime, and we used to vacation every summer back when I was 9, 10, 12 years old, at Lake Delavin. So, I know your country up there pretty well. Growing up in northern Illinois is very much like growing up in Oshkosh, or any of those other areas with the carnivals coming through, the autumn weather, with Halloween, and the sense of good and evil in a small town which you don’t even recognize.

When I got older I wanted to do a story about the traveling carnivals and the autumn weather and the love for the country that you and I have shared together. Illinois is not that much different. And it was about passing existence and sadness and joy. And I sort of put it all in one book. Something Wicked This Way Comes just about personifies more than everything else I’ve done, just about everything I think about life. You know, just the joy of being alive and the sense of passing time and losing friends and death coming and scaring you.

And in the novel I have Death coming into the town, and there are people trying to sell them things in return for selling their souls in a pact with Lucifer. It’s a combination of mythological things I suppose I picked up when I was younger out of other books. And with my own feelings about Illinois and Wisconsin as a child.

TANGENT: You’ve finished the screenplay for that, haven’t you?

BRADBURY: Yes, it’s been done for some time now. I’m looking for a director now. I was sort of hoping Sam Peckinpah would direct it but I’m still waiting to hear from him. I love that man. But, I’m not holding my breath, okay? (Laughing)

(Photos above from Archon XX, Oct. 1996. At right: Bradbury and old friends Julius Schwartz, Forrest J Ackerman, Ray Harryhausen)

Ray Bradbury interview copyright © 1976, 2012 Robert Jacobs and Tangent/Tangent Online.

All rights reserved.

(Note to diehard Ray Bradbury collectors: I have perhaps 5-8 copies of Tangent #5, Summer 1976 remaining. Along with interviews of Leigh Brackett & Edmond Hamilton, and Jack Williamson, there is a Bradbury article titled “A Feasting of Thoughts, A Banqueting of Words: Ideas on the Theater of the Future” which first appeared in Performing Arts for October 1975 and which Ray allowed us to reprint gratis. Then President of the Science Fiction Writers of America Andrew J. Offutt said of this issue, “This is the very best issue of any fanzine I have ever seen.” If you would like to acquire one of these last copies–printed by legendary SF editor Raymond Palmer–please send email with your offer to tangent.dt1@gmail.com.)