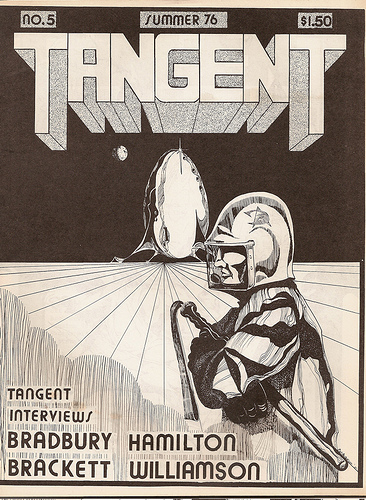

Tangent Online Presents:

An Interview with Leigh Brackett & Edmond Hamilton

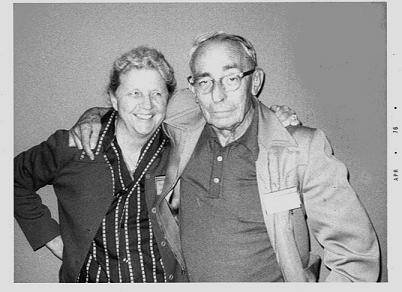

photo by Dave Truesdale

Interviewers:

Dave Truesdale and Paul McGuire III

Location:

Minneapolis, Minnesota

Event & Date:

Minicon 11

April 16-18, 1976

Interview originally appeared in Tangent No. 5, Summer, 1976

First reprinted in Science Fiction Review, ed. Richard E. Geis, May, 1977

Second reprint appeared in (the new incarnation of) Tangent: No. 4, January/February 1994, featuring original Special Appreciations by James Gunn and Jack Williamson

Introduction

Following our journey from Oshkosh, WI to Minneapolis, MN for Minicon 10 in April of 1975—our first real science fiction convention (see the William Tenn, Donald A. Wollheim, and Judy-Lynn & Lester del Rey interviews)—we were hooked. So back the small staff of Tangent (all three of us) went to Minneapolis for Minicon 11, in April of 1976. We were more prepared this time for the interviews we hoped to get, having done our homework on specifically selected authors. Among several others from that weekend (including Jack Williamson), the interview with Ed Hamilton and Leigh Brackett turned out to be, without question, the highlight of our convention. Seated comfortably in their hotel room one afternoon, we spent nearly two hours with them. Ed and Leigh put us at our ease immediately with their casual laughter and relaxed demeanor. Their good mood put us in a good mood, erasing any and all feeling of intimidation we might have felt. They were open and giving with their answers, often playing off each others stories about themselves and other writers they had befriended over the years, most notably stories concerning Ray Bradbury, Henry Kuttner, Jack Williamson, and John W. Campbell. I will never forget this interview, and the hours I spent with Ed and Leigh. They were two of the most friendly, warm, and wonderful people I have ever met.

A few hours before the presentation of the Hugo awards at the Los Angeles worldcon in 1996, Darrell Schweitzer and I bumped into each other and decided to grab a bite to eat before the festivities began. We talked about this and that, and I asked him about my belief that the Tangent Brackett/Hamilton interview was indeed the last one ever conducted with them both, as I had read another interview with them (by him) in a subsequent issue of Amazing. He informed me that his was conducted much earlier than mine, but that Amazing had held onto it for some time, and that indeed the Tangent interview was the very last interview ever done with them both.

Ed Hamilton was born on October 21, 1904 and passed away less than a year following the interview, on February 1, 1977.

Leigh Brackett was born on December 7, 1915 and passed away just over a year after Ed, on March 18, 1978. She turned in the first draft of the script for The Empire Strikes Back mere weeks before her passing.

Following its trio of print appearances over the past thirty-three years, the last one being almost sixteen years ago, we are happy now to present the interview–online–to an entirely new generation of SF fans, and to be able to include the pair of Appreciations by James Gunn and Jack Williamson for the first time online as well.

Following the interview I have a few closing remarks, and am reprinting for the first time a letter from then SFWA President Andrew J. Offutt with his thoughts on the interview, his letter originally appearing in Tangent No. 6.

I hope you enjoy the interview and its inside look at two of the most beloved figures in all of science fiction.

Ed and Leigh–

by

James Gunn

“Ed and Leigh.” I feel comfortable speaking about Ed Hamilton and Leigh Brackett in that way, even though I met them only a couple of times. They were that kind of people―unpretentious, courteous, friendly. I remember one meeting, although I do not remember the occasion or the circumstances (perhaps it was in a hotel room at the Cleveland World SF convention of 1955, although I remember a later meeting, perhaps at the L.A. Convention of 1972). They treated a relatively new writer (my first story was published in 1949 and my first two novels in 1955) like a respected colleague. At that time I had no idea that Leigh was a major Hollywood screenwriter for Howard Hawks. She was Leigh Brackett, author of romantic space epics, and he was Edmond Hamilton, author of adventure space epics, and they helped make SF what it was.

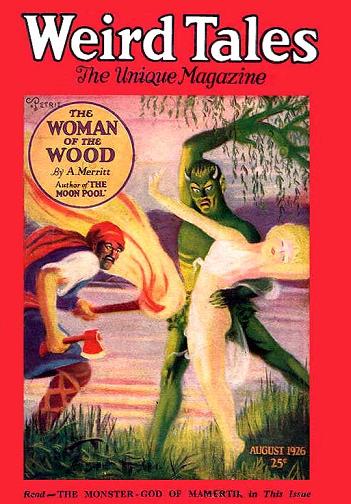

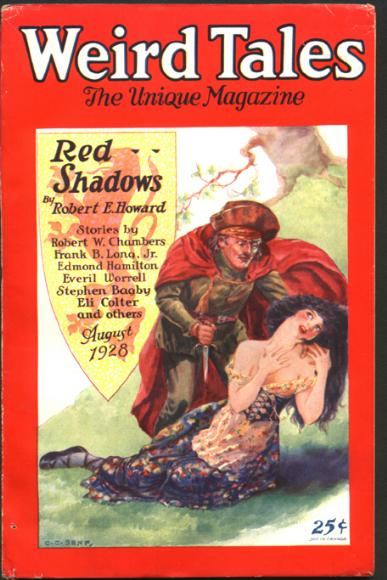

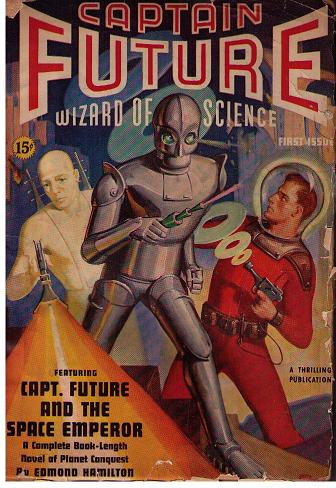

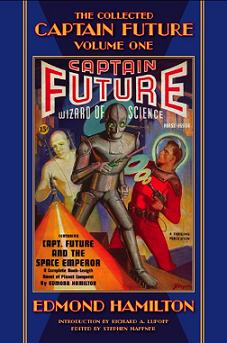

Particularly Ed, whose first story was published in 1926 in Weird Tales [August, 1926 cover at left] and whose “Crashing Suns” two-part serial in the 1928 Weird Tales, [Aug. 1928 cover at right] and later Interstellar Patrol stories, did as much to create the space epic tradition as E. E. “Doc” Smith’s Skylark novels. Jack Williamson has said that Weird Tales never rejected a Hamilton story. Ed made a bad career move, although perhaps a necessary financial move considering the limited opportunities and payments available to SF writers of the time, when he took on the assignment of writing, virtually single-handed, the quarterly Captain Future novels in the magazine of that name from 1940-1944 and later in Startling Stories and episodes of Superman comics when Standard Magazines editor Mort Weisinger moved to DC comics.

Particularly Ed, whose first story was published in 1926 in Weird Tales [August, 1926 cover at left] and whose “Crashing Suns” two-part serial in the 1928 Weird Tales, [Aug. 1928 cover at right] and later Interstellar Patrol stories, did as much to create the space epic tradition as E. E. “Doc” Smith’s Skylark novels. Jack Williamson has said that Weird Tales never rejected a Hamilton story. Ed made a bad career move, although perhaps a necessary financial move considering the limited opportunities and payments available to SF writers of the time, when he took on the assignment of writing, virtually single-handed, the quarterly Captain Future novels in the magazine of that name from 1940-1944 and later in Startling Stories and episodes of Superman comics when Standard Magazines editor Mort Weisinger moved to DC comics.

It was surprising to learn that Leigh was the sophisticated screenwriter for such Howard Hawks’ films as The Big Sleep (with William Faulkner), Hatari, El Dorado, Rio Lobo, and Rio Bravo, but perhaps even more startling was the discovery of Ed’s “What’s It Like Out There?” in the December 1952 Thrilling Wonder Stories and to realize that the “world wrecker” or “world saver” – take your pick – was also a skillful and sensitive author of naturalistic, near-future fiction. Jack Williamson has said that Ed always was capable of such skillful renderings of upcoming reality, but that editors wouldn’t publish them. And, indeed, the original version was written in 1933 and was put away for twenty years until the time was ripe.

It was surprising to learn that Leigh was the sophisticated screenwriter for such Howard Hawks’ films as The Big Sleep (with William Faulkner), Hatari, El Dorado, Rio Lobo, and Rio Bravo, but perhaps even more startling was the discovery of Ed’s “What’s It Like Out There?” in the December 1952 Thrilling Wonder Stories and to realize that the “world wrecker” or “world saver” – take your pick – was also a skillful and sensitive author of naturalistic, near-future fiction. Jack Williamson has said that Ed always was capable of such skillful renderings of upcoming reality, but that editors wouldn’t publish them. And, indeed, the original version was written in 1933 and was put away for twenty years until the time was ripe.

In many ways science fiction has been an editor’s medium, for good or bad. Editors such as John Campbell, Anthony Boucher and J. Francis McComas, and Horace Gold, and later Michael Moorcock, moved SF into new and uncharted areas. But who knows where writers such as Ed and Leigh might have taken their work if they had been encouraged in the right fashion at the right moment? But perhaps their space epics were essential to where SF has arrived, and they are no small contribution to the archives and traditions of the field.

Ed and Leigh–

by

Jack Williamson

Edmond Hamilton and Leigh Brackett were among my first and best friends. Ed and I were writing science fiction before Gernsback named it science fiction. We met Leigh a dozen years later. In those early days, before fan clubs and fanzines, almost the only way to find other fans was through the letters in the back pages of the magazines. Jerry Siegel, who later invented Superman, gave me Ed’s address. I wrote him after I read “The Comet Doom” in Amazing, and we met in Minneapolis in 1931 for a boat trip down the Mississippi. We got along well enough, and kept in touch the rest of his life.

Edmond Hamilton and Leigh Brackett were among my first and best friends. Ed and I were writing science fiction before Gernsback named it science fiction. We met Leigh a dozen years later. In those early days, before fan clubs and fanzines, almost the only way to find other fans was through the letters in the back pages of the magazines. Jerry Siegel, who later invented Superman, gave me Ed’s address. I wrote him after I read “The Comet Doom” in Amazing, and we met in Minneapolis in 1931 for a boat trip down the Mississippi. We got along well enough, and kept in touch the rest of his life.

He was a more interesting person, with more wit and wider interests than you might guess from his early work. He was the ultimate pulpster. He wrote fast, punching the keys with two fingers, punching them so hard at the climax that the o’s punched holes in the paper. He sent his stories out in first draft, and he told me once that Weird Tales had accepted forty without a rejection.

The early stories may have been crude, but they moved fast, they were exciting, and they were filled with the sense of wonder. Something that today’s science fiction has almost lost. The wonder was very real then. Travel in space, travel in time, the exploration of the future – such ideas are all worn thin now, from endless variation in books and films and tv shows, but they were fresh and very wonderful then.

I met Leigh when she came to the motel where Ed and his agent, Julie Schwartz, and I think his editor at Standard Magazines, were staying on a visit to California. The date was probably 1940, the year her first story was published. She and Ed were married in 1946.

Her work had a smoother literary finish than his ever did, but it had wonder enough and action enough, along with the appeal of her hard-bitten, hard-fighting heroes and the color and romance of the worlds she created for them. As much as anybody, she was pioneering the way for the Star Wars films. It’s fitting that she later had a share in their creation, writing the original script for The Empire Strikes Back.

Her work had a smoother literary finish than his ever did, but it had wonder enough and action enough, along with the appeal of her hard-bitten, hard-fighting heroes and the color and romance of the worlds she created for them. As much as anybody, she was pioneering the way for the Star Wars films. It’s fitting that she later had a share in their creation, writing the original script for The Empire Strikes Back.

By the way, their papers are in the science fiction collection at Eastern New Mexico University, here in Portales.

TANGENT: Ed, how did you meet Leigh, and when was that?

HAMILTON: Well, it was in 1940. Mort Weisinger and Julie Schwartz, my old friends, were out in Beverly Hills from New York on vacation. Julie was my agent at that time, and Jack Williamson and I went over to see him in Beverly Hills, and Julie said, “I have a client here, a young girl who lives in Los Angeles, and she’ll be coming through this morning to see me.” So when she arrived she was overcome with awe to meet two great science fiction writers like Jack Williamson and myself; but I was quite kind to her, put her at her ease… I think I’ll let her tell her version of it now (laughing to Leigh).

BRACKETT: (Laughing) Well, they were both looking thoroughly auctorial; they were both wearing sweatshirts, looking like geniuses. I nearly fell through the floor. Jack Williamson, Edmond Hamilton, they were the two great names. Seven years later he got around to asking me to marry him.

HAMILTON: There was a considerable amount that went between all that. In 1941 I came back out to California with Julie. We lived in Los Angeles in a bungalow that was kind of the center of the science fiction group out there, and we would get together with some beer and booze and sit around and drink. Well, she would come sometimes in the afternoon and we would always have some cake for her. We didn’t feel that a nice young lady should be offered booze so we always had a nice piece of cake for her. I think she would have preferred the booze–

BRACKETT: I would have preferred the booze, except when I went home my mother would have said ”(Gasp!) You’ve been drinking with those terrible people!”

HAMILTON: In 1946 I came back out to Hollywood and a few months later we were married.

BRACKETT: Well, one thing that came between us was the war, of course. He was back in Pennsylvania where he was living then. We had to correspond.

TANGENT: Which of you began writing first?

HAMILTON: First? I did. I sold my first story in 1926, fifty years ago. But she’s not that old (smirking).

BRACKETT: (Laughing) Why, I was just a child at that time.

TANGENT: What led you into writing science fiction? What were the reasons?

HAMILTON: Economic reasons were never one of them because it was one of the poorest ways to make a living. Some people, myself included, are born with a feeling about these things. In my case I couldn’t even read. This was on a farm in Ohio back in 1908 when I was four years old. I got hold of some magazine that contained an article by H. G. Wells called “The Things That Live on Mars.” It was, as I see it now, a follow-up to his very successful The War of the Worlds. And it had these pictures of tall, slender trees; strange looking Martians moving about. I looked at that magazine until it wore out. I wasn’t yet able to read it, to read the article, but those pictures! I sat and wondered if Mars was a long way off and if it was a very strange place. This feeling I say; I think people have a bent toward this. That is to say, I had a very large family and I don’t think any of them read anything but maybe my first story. They just had no interest in science fiction. They were all great readers, but not science fiction.

TANGENT: Back in those days it was considered second-class literature, wasn’t it?

HAMILTON: Very much.

TANGENT: What changes have taken place in the writing since those early days?

HAMILTON: It has of course changed a great deal. I’m thankful that I got into it at a very early day because frankly the first story I wrote I could never sell today. It wouldn’t be accepted; it would be crude. In those days science fiction was in very little magazines, they were very anxious for printable material, therefore a lot of us―Jack Williamson and I were talking about this last night―succeeded in breaking into print and getting a little money for it, very little, while we learned to write. Nowadays the youngsters have a much harder time. They’ve got to write really good from the very first story. Being a product of the older days I can’t help feeling affection for those old magazines. I prefer the old stories, but that doesn’t change the fact that the field has advanced in literary quality, technique, and everything. We chaps, most of us who started in the old days, could never make it now, with what we did then.

TANGENT: How had the field changed by the time you got into it, Leigh?

BRACKETT: Well, I sold my first story in 1939. I had been trying for a couple of years to break into the field, and it just took me longer. He sold his first story, the first story he ever wrote, and then the next forty without ever having a rejection. On the forty-first someone wanted a few things changed–

HAMILTON: Dave Lasser from Wonder Stories. He wanted something changed and this so hurt me that I just threw the story away. I was spoiled, you see (chuckling). Material was scarce and they weren’t paying much and I was thoroughly spoiled. I never did have a story rejected by Weird Tales in all those years. And uh, this is hard on a writer.

BRACKETT: When I started everybody advised me not to write science fiction because there was no money in it.

TANGENT: You had written other things before that?

BRACKETT: I tried. I mean I had tried because I was heading for the adventure and short story market. And unfortunately I hadn’t been anywhere, I didn’t know anything, and I was bucking the biggest names in the business. I got nowhere, understandably. Finally I figured I was wasting my time and knew that what I really wanted to write anyway was science fiction. If I want to write about Mars who’s going to contradict me? Nobody’s been there. And besides, that’s what I really wanted to write about so that’s what I did. Sure enough, there wasn’t a heck of a lot of money in it, but it was a heck of a lot of fun; there’s some awfully nice people.

It was a very chummy world in those days because there weren’t very many of us writing, or reading science fiction, and I had not, at that time, connected with any fan group. In fact, I didn’t even know there were such things. Henry Kuttner was the one who introduced me to the LASFS out there, but that was after I had broken in–

HAMILTON: The first date we ever had we went down to the science fiction meeting. Jack Williamson drove down, and he and I sat in the front seat and we put her in the back seat. I think I made a bad impression; I was smoking, then as even now, when a large chunk of hot ash went back into her eyes. Jack made these commiserating sounds but all I said was “Is it bleeding?” or something like that (laughing). She must have thought I was a very hard character.

BRACKETT: But you didn’t go around bragging that you wrote science fiction because people either had never heard of science fiction and said “What’s that?” and then you’d try to tell them and they’d say “Oh, it’s that Buck Rogers stuff,” and you were always getting advice to write something good, like in the Ladies Home Journal―to write nice stories. My family didn’t read my stuff, either. It was such a small world. We kind of clung to each other, you know. A fellow nut you would think of out there in that outer windy darkness…you kind of cling together because you speak the same language.

HAMILTON: Wherever you went, if you knew of a resident science fiction writer you would call him on the phone, announce yourself, and you were always instantly welcomed with open arms. You would sit up till all hours talking about this, or that, about science fiction, because in those days there were no clubs. But we were always glad to see each other because we felt so lonesome.

(To Leigh): You had quite a strict family back then.

BRACKETT: Oh yes, very.

HAMILTON: I got you back at ten o’clock one night and you got quite a scolding for being out that late. A few years later during the war I picked up this novel she had written called No Good From a Corpse. It was a tough private-eye novel. The hero was named Edmond, wasn’t he?

BRACKETT: Um-hmm.

HAMILTON: I always felt you were dreaming of me (laughing). I hoped.

BRACKETT: (Chuckling) I liked the name.

HAMILTON: She had written this novel that was full of Humphrey Bogart-type characters. “I grabbed her and said, ‘Doll, you’re quite a dish,’ “ and all this sort of thing, and people were shooting other people up, and I told my folks…Betty and Phil had looked at that novel…and I said I didn’t know where she got all this experience because I couldn’t keep her out past ten o’clock at night (laughing).

HAMILTON: She had written this novel that was full of Humphrey Bogart-type characters. “I grabbed her and said, ‘Doll, you’re quite a dish,’ “ and all this sort of thing, and people were shooting other people up, and I told my folks…Betty and Phil had looked at that novel…and I said I didn’t know where she got all this experience because I couldn’t keep her out past ten o’clock at night (laughing).

BRACKETT: Well, I’ll tell you where I got it. I got it from reading Hammett and Chandler.

TANGENT: Leigh, how did you meet Ray Bradbury?

BRACKETT: Ray was a member of the LASFS group. This was before he started to sell, so he was writing like mad and trying like mad to break in. (To Ed): That summer that you and Julie were out there, Ray was selling newspapers on the corner about a block or so away from our place.

HAMILTON: Julie always liked Ray very much, so when he’d lay in some beer and whiskey and so on for our evening parties, he would always get some Coke for Ray. He was such a kid he didn’t drink anything and Julie would say, “I’ll get a little Coke for the kid.” As I say, Ray was very young, and he would bring his stories over for Julie and I to read. Finally I told him, “You don’t want us to tell you how to write. You know very well what you want to do and you’re going to do it your own style. What you’re bringing these stories over for is that you want us to tell you they’re good. They’re good. So just go ahead and write them.” I think it was that summer he published his first story that he collaborated with Henry Hasse on, and it appeared. Well, he brought the magazine over to show us and he showed it around, was just beaming like the sun, and then he was so overcome that he took the magazine like this and he kissed it and kissed it (laughter from all).

He was an awfully nice kid then, and a nice man now.

TANGENT: Ed, how did you get involved in writing comic books?

HAMILTON: Well, of course, the main attraction with comic books was that they paid so much more than science fiction. Mort Weisinger, an old friend and pal of mine, had moved over to the comics from Standard Magazines. In 1941 he wanted me to work for him over there, and I thought about it and then told him I didn’t want to be bothered by it. After the war, actually it was VJ Day, he wrote and said Ed have you thought better about it? Well, during the war markets were very poor in science fiction and I was having a rough time making a living, so Mort knew I didn’t like to live in New York, so he said if you’ll come up and spend a week with us we’ll go over and show you how to do these things and then you can do them by mail. So I went up…and rather liked doing them as a matter of fact, being with the home crowd there; being science fiction fans they liked science fiction, they liked these science fictional touches, it was a bit easier for me. I wrote them off and on for twenty years really―from 1946 to 1966. I enjoyed it. Not as much as writing a story, but…it was not by any means just hackwork. We started to travel quite a bit about that time and I had to quit for that reason.

HAMILTON: Well, of course, the main attraction with comic books was that they paid so much more than science fiction. Mort Weisinger, an old friend and pal of mine, had moved over to the comics from Standard Magazines. In 1941 he wanted me to work for him over there, and I thought about it and then told him I didn’t want to be bothered by it. After the war, actually it was VJ Day, he wrote and said Ed have you thought better about it? Well, during the war markets were very poor in science fiction and I was having a rough time making a living, so Mort knew I didn’t like to live in New York, so he said if you’ll come up and spend a week with us we’ll go over and show you how to do these things and then you can do them by mail. So I went up…and rather liked doing them as a matter of fact, being with the home crowd there; being science fiction fans they liked science fiction, they liked these science fictional touches, it was a bit easier for me. I wrote them off and on for twenty years really―from 1946 to 1966. I enjoyed it. Not as much as writing a story, but…it was not by any means just hackwork. We started to travel quite a bit about that time and I had to quit for that reason.

TANGENT: Were you writing much science fiction during that time?

HAMILTON: Oh, yeah. I wrote as much science fiction as I possibly could. I didn’t want to give up that market. To me comics were a temporary thing. I was not able to write as much as I wanted, but I kept something going all the time. Every now and then I’d let the comics wait and do a short novel.

HAMILTON: Oh, yeah. I wrote as much science fiction as I possibly could. I didn’t want to give up that market. To me comics were a temporary thing. I was not able to write as much as I wanted, but I kept something going all the time. Every now and then I’d let the comics wait and do a short novel.

TANGENT: Leigh, there were very few women writing science fiction during the 30’s, 40’s, and 50’s. Were there any special problems you had to face being a woman?

BRACKETT: There certainly wasn’t with me. They all welcomed me with open arms. There were so few of us nuts that they were just happy to receive another lamb into the fold. It was simply that there wasn’t many women reading science fiction, not many were interested. Francis Stevens sold very fine science fiction stories to Argosy back in 1917, back around that period.

HAMILTON: Her name, you see, could have been a man’s name and Leigh’s name could have been a man’s name. Catherine Moore, who wrote SF long before you did, and a dear friend of ours, wrote under the name of C. L. Moore. Now, I don’t think there was much real bias on the part of women’s libbers–

BRACKETT: I never ran into any. On some of the first few stories I sold people would write into the letter columns and say Brackett’s story was terrible, women can’t write science fiction. That was ridiculous, there were women scientists you know, there’s no problem there. What they were complaining about was that I didn’t know how to write a story (chuckling). When I learned a little better I stopped hearing this. What they were complaining about was the quality really, not…you know. The editors certainly, there was never any problem with them.

HAMILTON: Hedda Hopper, in her column that she had, went into how Howard Hawks wanted to do this movie on Raymond Chandler’s novel The Big Sleep. Hawks had picked up this detective story and so he told his agent, you know, this chap would make a good screenwriter on this, so get Mr. Brackett. So in this newspaper column it was reported how astonished he was when this fresh-faced girl that looked like she had just come from a school-girl tennis court suddenly turned up. He gulped and went right on with it (chuckling).

BRACKETT: But no, there was never actually any discrimination against women screenwriters. The first job I ever got was at Republic and the highest paid person on the lot was a woman. The discrimination against women came in later, much later, when television came along with all these male-oriented western series and detective series, and they figured a woman wouldn’t be able to write that kind of thing. Which is where the problem came in. Dorothy Fontana gave a very concise, intelligent discussion of that one night out there at UCLA. This is breaking down now. In other words, they are reading the script to see if it’s a good script and not who wrote it.

TANGENT: What about in science fiction? Has it changed at all?

BRACKETT: As I say, there never was any discrimination as far as I know of, but a great many more women are writing science fiction than ever before.

TANGENT: What about the women’s libbers in the field now, say Joanna Russ for instance?

BRACKETT: Well, Joanna’s got her own axe to grind. She’s got her own way of looking at things, but I never worried about it much one way or the other.

TANGENT: It’s like she and others assume the problem existed and are working from there.

BRACKETT: Well, certainly in the science fiction world it never did. It was just that not many women read it. Kate Wilhelm had an interesting answer to that. Somebody asked, at this seminar, why or how she came to get into SF, and she said when they put Sputnik up all of a sudden this became real and she realized this was affecting the world she lived in and the world her children lived in. I wonder if this was typical of a lot of women who were not interested in science fiction until it became something of a reality. You know, until it had a definite effect on themselves and on their futures, that they began to see it in a different light. I don’t know if that would apply to any others or not, but certainly there weren’t many women reading or writing it in the old days. In fact, this is why they said that the field would never be successful in a broad sense. You know, you didn’t have the women readers.

HAMILTON: If I may say so, you have an advantage in that you’ve always written like a man. You read her stuff and it’s a male type of writing, with all of these sword-swinging characters and this sort of stuff. I might write a tender little fantasy once in awhile, but her, it’s all blood and guts (chuckling).

TANGENT: Is that a wish-fulfillment on your part, Leigh?

BRACKETT: (Laughing heartily) Gosh, I hope not. It’s the type of thing I always liked to read and it was the only thing I ever wanted to write. I’ve written things like The Long Tomorrow which was not the sword-swinging epic type, but domestic problems always bored me. I mean they bore me personally (chuckling).

HAMILTON: Oh, no, no, don’t say that.

TANGENT: What other influences did you have besides Burroughs and Merritt?

BRACKETT: I’d say Burroughs of course was the first one. I was introduced to Edgar Rice Burroughs at a very young age. And of course I immediately took the plunge and that changed the course of my life right there.

HAMILTON: That was true of nearly all of us of that generation. We sort of grew up on Edgar Rice Burroughs. I had read much other science fiction; I totally admired H. G. Wells. But Burroughs seemed to be the one we all tried to model after. I think Ray told us his first story was written because he couldn’t―his family being hard-up at that time―he couldn’t afford to buy the new Burrough’s Mars novel that came out. He’d seen it in the bookstores but he couldn’t afford to buy it, so he sat down and wrote it.

BRACKETT: I think my first writing effort was somewhat the same. I was a great fan of Douglas Fairbanks, Sr. I saw every one of his films over and over and over, and just loved Fairbanks. My favorite was The Mark of Zorro or something, and I wanted a sequel and there wasn’t any, so I started writing one on little scraps of paper. Burroughs influenced me more―well, the Mars stories, all my Mars stories came out of Burroughs―I tried never to exactly copy his Mars, I tried to make it my own, but I think my fascination for Mars came from the fascination for his Mars.

BRACKETT: I think my first writing effort was somewhat the same. I was a great fan of Douglas Fairbanks, Sr. I saw every one of his films over and over and over, and just loved Fairbanks. My favorite was The Mark of Zorro or something, and I wanted a sequel and there wasn’t any, so I started writing one on little scraps of paper. Burroughs influenced me more―well, the Mars stories, all my Mars stories came out of Burroughs―I tried never to exactly copy his Mars, I tried to make it my own, but I think my fascination for Mars came from the fascination for his Mars.

Now, Hammett and Chandler were very strong influences, and James Cain, whose style I greatly admired. I tried to use what I considered to be very good and very powerful in the detective story genre and use it in science fiction. “The Halfling” is very much in the detective story style, which seems to me to work out very nicely.

TANGENT: What do you think of the different awards that have sprung up that they didn’t have in the early days? Do you feel a sense of loss or anything since both of you have never won one?

BRACKETT: No. I’m always happy for the people who get the awards. You know, I’d be delighted if I ever got one. I was up for a Hugo once on The Long Tomorrow. I don’t know…I just don’t worry about it.

BRACKETT: No. I’m always happy for the people who get the awards. You know, I’d be delighted if I ever got one. I was up for a Hugo once on The Long Tomorrow. I don’t know…I just don’t worry about it.

HAMILTON: I’d be delighted to get one, too. I was also nominated for one, but most of our science fiction has been in the adventure/entertainment scene. If you don’t have Big Thinks in it the people who vote on these things are not greatly impressed. If they can understand every word of it then it can’t be great, you know? That’s their attitude.

TANGENT: That seems to be rather paradoxical when you think of how many people today would like to see more space opera or pure adventure or whatever.

HAMILTON: I was reproaching Bob Tucker last night for inventing the term space opera. I told him there had been only one true space opera, and that was a Swedish opera Aniara (sp). That’s the only opera that’s about space. However, I think the thesis of what they call space opera is that the conquest of space would be a great adventure. And anybody who watched Armstrong or Aldrin taking the first steps on the moon or listening to those messages coming in on Apollo 13 when they were in trouble―that was pure space opera.

I was happy to see that all our astronauts all look exactly like they came off old science fiction covers.

TANGENT: Look what happened to the astronauts who’ve come back from space; one found God, one became neurotic, one is experimenting with parapsychology and so forth. Do you think we’re perhaps not ready for space?

BRACKETT: Oh, I don’t think so. I think people who’ve gone beyond into the unknown, whether it was beyond the Pillars of Hercules or across the Atlantic or wherever, when you get out into the strange and totally unknown―of course this time we’re really going out beyond, even our own Earth―but we can cope with it.

HAMILTON: I was interested in the remarks of the astronauts on how beautiful and warm Earth looked like from a distance. This is the feeling I used to try to get into stories, and it was stated in classic form years ago by Bob Heinlein in his story The Green Hills of Earth. He did the ultimate story on that kind of feeling―and that came true. Those remarks could have been taken right out of Bob’s story.

TANGENT: What moves you when you write? What do you try to put into your stories?

HAMILTON: I always try to get a little emotion into the fact that you are doing something that nobody has ever done before; removing yourself completely from the planet from which we all have been bound. I’ve always tried to imagine myself in that position and create the mood as well as I can, because I think that would be a great experience.

When Apollo 12 took off we were at the launching at Cape Kennedy. We whangled reporter’s passes so we could sit up close. We were just a bit dashed when we heard the President and Vice-President weren’t that close. They said they didn’t want to risk them―but they sure will risk me! (laughing) But it was a tremendous experience you know, after having been involved in all of this since the 20’s to see it actually happening. This one was more dramatic than most because when it went up it was hit twice by lightning bolts. They were in doubt up until the last moment whether they would launch it or not because they had some storm activity. Leigh turned over to me and said, “Somebody out there doesn’t want them.”

BRACKETT: You know, it was just a static discharge. But they did lose total power for a full minute and they had a near squeak on that one.

TANGENT: When you began writing back in the 20s did you ever dream that technology would progress so quickly you would be able to see that?

HAMILTON: I didn’t think it would happen in my lifetime. I thought it would happen, but not in my lifetime. A chap came from Sweden to visit us last winter―he was in this country on a journalistic tour―and he belonged to a club in Sweden called The Captain Future Club. He had read those Captain Future stories I wrote―which were really written for teenagers―he was asking me about this very point and I said sometime long after I’m gone it will surely be done, but he pointed out to me that in Captain Future I said the first moon landing would be in 1970…which was pretty close. And he said, “Didn’t you believe that?” And I said I don’t think I really did. But I was trying to bring within comprehension of those science fiction readers that the year 2000 seems as remote as all hell, drop it down thirty years to 1970 and it’s a bit easier to comprehend it. (Chuckling) It shattered his faith a little bit, but…

HAMILTON: I didn’t think it would happen in my lifetime. I thought it would happen, but not in my lifetime. A chap came from Sweden to visit us last winter―he was in this country on a journalistic tour―and he belonged to a club in Sweden called The Captain Future Club. He had read those Captain Future stories I wrote―which were really written for teenagers―he was asking me about this very point and I said sometime long after I’m gone it will surely be done, but he pointed out to me that in Captain Future I said the first moon landing would be in 1970…which was pretty close. And he said, “Didn’t you believe that?” And I said I don’t think I really did. But I was trying to bring within comprehension of those science fiction readers that the year 2000 seems as remote as all hell, drop it down thirty years to 1970 and it’s a bit easier to comprehend it. (Chuckling) It shattered his faith a little bit, but…

One of those chaps tried to send along with Apollo 11, the first moon landing, a Captain Future novel. He wrote endless letters to NASA saying, “This is the way it will be, this should go along!” (Laughing) “A copy of Captain Future on the Moon!”

BRACKETT: They wrote back and told him they were sorry but they didn’t have room.

TANGENT: To take on the other side of the coin now; do you think science fiction should have a role or function in society? What part does it play?

HAMILTON: That’s a hard question to answer. I would say that offhand…no. But there has been some science fictional satire in the past that has helped to bring about real social changes. I wouldn’t want to be dogmatic either way about it.

BRACKETT: I think science fiction is such an enormously broad term that it includes so many things. I think actually the entire field has had a social impact in that it has prepared―subliminally, almost―a generation to believe in space-flight, to believe in technological advances. They have a much wider view of the universe than they had.

HAMILTON: I think we have had a part at least in familiarizing the idea of going into space, because when I was a youngster people would say, “I’d as soon do that as go to the moon,” or “I’d as soon do this as fly to the moon.” You don’t hear that anymore. For a long time you haven’t heard it. That was the ultimate in impossibility.

TANGENT: What interests you now the most in science fiction?

BRACKETT: I’m interested mainly in never trying to mold the field into one particular thing. I think it should be free to have every type of thinking, every type of story. I think you should have the ecological stories, the political stories, the Big Think type of story. I mean, what anybody wants to write. What I hate to see are the occasional attempts that are made, periodically, none of them ever last very long, to mold the field into one particular thing, and say science fiction has to be such and such and so. In other words, just what I happen to think science fiction should be. It’s the one field that you cannot really whack down into one simple thing–

TANGENT: What about John Campbell?

HAMILTON: Yes, he did try to do that, and that is one of the chief reasons I didn’t like to work for John Campbell. I sent him one story and never again. He bought it, but I could not subordinate every idea I had into the Campbell formula. Added to which, he didn’t particularly like his writers to be writing for the lesser science fiction magazines. Damn few could make a living writing for John Campbell.

I admired Campbell. I testified to this the other night when we were talking about the old days. In fact, he was one of the great pulp magazine editors. Yet, science fiction did not begin with John Campbell. There were other editors, who may not have had as big an influence, although I think Tremaine was right up with Campbell there, in the early Astounding Stories. But, Campbell had kind of a dogmatic, rigorous mind; it has to be this way or that way, but it can’t be that way. He was a difficult chap to work for. She sold her first stories to him.

BRACKETT: And I still don’t know why he bought them. They weren’t very good stories. Unless he hoped he was discovering a new writer. Unfortunately I didn’t go the right direction. I kept trying to sell him things because he was the top market, but when you wrote a Campbell-type story and it didn’t sell then you had no place else to go with it. He rejected one of mine rather viciously, so I decided it was a waste of time, and never–

HAMILTON: He was a very stiff, odd, portly sort of a chap. I never sent him a story after 1938 because I had to revise that one. First, to suit John’s idea, and then to suit John’s wife’s idea. That was a little hard to do, so I never sent John any more stories.

Sprague de Camp told me a few years later that he’d always been irked with me because I didn’t send him any more stories. And I told Sprague that he no doubt wanted the pleasure of rejecting them. When I’d see John at science fiction conventions we were somehow always the invisible people; he couldn’t quite see us. Several years ago I saw him sitting at a convention and I walked over and said to him, “What the hell’s the matter with you, John? You can’t see me anymore. We were friends before you ever edited that bloody magazine. What is this, anyway?” And he just stammered, “Uh, uh, uh.” But I think he was glad I had broken the ice because he didn’t want to carry on this thing much longer. And I was glad I had too, because he only lived a couple of years longer. After all this long freeze we’d had we ended up with our arms around each other, and he turned to me and said, “Ed, we old-timers have got to stick together.” (Chuckling)

BRACKETT: One big trouble I had trying to sell to Campbell was of course the fact that I did not have any great scientific or engineering background. And this is one thing he insisted on in his stories, and I admit uh, Ed had a great background in physics and electrical engineering that I didn’t have, and I tried to make up for it by writing a new type of story. But it was just not Campbell’s type of story.

HAMILTON: When Ray tried to get scientific once (laughing) –

BRACKETT: He had this story where he had written ‘hundreds and hundreds of degrees below zero,’ and somebody wrote in and said, “Ray, haven’t you ever heard of absolute zero?” And he said, “No. What’s that?” (Laughing) Now of course I don’t think Ray ever sold to Campbell–

HAMILTON: He never sold but tried like anything.

BRACKETT: As I recall it, Astounding was a brilliant magazine too, in those days. You had the young Heinlein, the young Sprague de Camp, A. E. van Vogt; they were all starting out in writing and wrote beautiful, brilliant stuff. It wasn’t until some years later that Campbell got a little bit fossilized and the magazine got a little bit fossilized, it seemed to me.

HAMILTON: Oh, no doubt about it. He wanted all of us to write for him in the early days. He was anxious to get the magazine on a firm footing and he had a wide acquaintance with all of us old-timers. He was one himself. He became, oh let’s say, the Pope of science fiction. He felt his position very keenly. And as I said, he got to the point where he didn’t like his writers to write anything for these inferior science fiction magazines.

BRACKETT: And he alienated quite a few of them by getting off onto these kicks. He went off on a psionics kick and there for awhile there it looked like all the stories were cut from the same bolt of cloth. Then he got into the Dianetics thing, with L. Ron Hubbard and Scientology.

HAMILTON: Remember he demonstrated the Heironymous Machine? That’s silly stuff. And so everybody was much pained by this. In fact, at Peterborough in England we were at a convention and some of those who attended were making some bitter remarks about him and this nonsense, and I got kind of angry at this despite the fact that John couldn’t “see” me anymore, so I got up and made a passionate defense of him. And I said, “He’s the trunk of the whole science fiction tree and you’ve kissed his feet for years, and now because he has a momentary aberration on this matter why are you all turning on him?”

It was unfair. It was dirty pool. They went around licking his cuffs all of the time and then they turned on him. But anyway, he didn’t like his writers writing for the inferior science fiction magazines. The only two writers who could write for Campbell all the time and the other magazines all the time were Murray Leinster and Henry Kuttner. Murray, of course, was an absolute pro. He could write anything for anybody. I used to ask Henry, “How do you do that? Do you slant your stories for Astounding?” He said, “No. I never slant a thing.” I’ll bet he unconsciously slanted them.

BRACKETT: Oh, you know it. When you definitely feel you are going to write a story for somebody whether you sit down and say I’m going to slant it or not, in the back of your mind that little quiet censor is back there; you sit down and do it a certain way, because if you didn’t you know it’s not going to come out right.

TANGENT: Were the pulps ever taken seriously by critics?

HAMILTON: They were, as a whole, cheap lowdown magazines and nobody cared much what was printed in them, but they gave science fiction a chance to expand its wings into all kinds of ideas. If you were writing for The Saturday Evening Post you found all kinds of taboos, whereas in the pulps, which few people cared about, anything went, just so long as it was effective. I think they were very good.

The only time a serious critic paid any attention to the science fiction magazines was in 1930. A famous British essayist of that time, William Balitho (sp) came to New York to write articles for The New York World about the American scene. He was absolutely fascinated by the pulp science fiction magazines and he wrote a beautiful article, on that long ago day, on the pulp science fiction magazines. He was probably the first serious critic to mention Lovecraft’s name. He said Mr. Lovecraft was a lot better than most of the serious novelists that they gave acclaim to. He added that a man who could read Galsworthy about society and Arnold Bennett about marriage and who can’t read these crude little magazines is completely unliterary, without realizing it. And he ended up predicting; he said someday these magazines, or the tattered copies of them that remain, will sell for more money than the first editions of our most famous novelists of today. And that is true.

TANGENT: In The Big Sleep, Leigh, there’s always a question Bogart fans seem to ask: Whatever happened to the chauffeur? He just dropped out about halfway through.

BRACKETT: The whole thing is confusing; the novel is confusing. I was down at the set one day and Bogart asked me who killed Owen Taylor, the chauffeur, and I said I didn’t know, and they asked Bogart and he didn’t know, and Hawks said let’s send Chandler a wire and find out, and his answer came back, “I don’t know.” It’s a very confusing plot and one of my favorite novels because the forward momentum is so tremendous and the characters are so interesting that you really don’t care.

BRACKETT: The whole thing is confusing; the novel is confusing. I was down at the set one day and Bogart asked me who killed Owen Taylor, the chauffeur, and I said I didn’t know, and they asked Bogart and he didn’t know, and Hawks said let’s send Chandler a wire and find out, and his answer came back, “I don’t know.” It’s a very confusing plot and one of my favorite novels because the forward momentum is so tremendous and the characters are so interesting that you really don’t care.

HAMILTON: The Big Sleep appeared in the summer of 1946. I was assiduously playing court to this young lady, and so I was living with my sister in Arcadia and I had to go all the way downtown—not having a car at that time―to see that. Well, I got in on the middle of that damn picture, and let me tell you…it’s confusing enough when you get in on the beginning of that picture. But the picture improves; by that I mean that when you overcome all the mind boggling difficulties with plot and so on– I liked it better than I ever used to. It really had a beautiful tempo.

TANGENT: What was it like working with William Faulkner? I’ve heard a lot about his peculiarities.

BRACKETT: Well, he did used to disappear in the middle of a script from time to time. It didn’t bother me because in any real sense we didn’t work together. This was my first big job; I had had one job at Republic a month or so before doing a thing called The Vampire’s Ghost, and I was three weeks on the script with another writer, and they shot the film in ten days and that was two days over schedule (laughing). They fired the cameraman after the second day because he was taking too much time. But uh, it was not the greatest film ever made.

So then this thing was dropped into my lap because Howard had read the book and liked the dialogue and put me under contract, and I’m making this thing with Humphrey Bogart, who, you know, is my favorite actor, and William Faulkner’s already on the script. I walk in, you know, feeling about this big and I think how in the world am I going to work with Faulkner. Well, there was no problem. He greeted me courteously. He put the book down and said, “We will do alternate sections. You will do these chapters and I will do these chapters,” and so on. But that’s the way he wanted it done. He turned around and walked into his office and I never saw him again, except to say good morning. He lived behind a wall about eight feet thick. I think you could have worked with that man for ten years and never known him. He had a few close friends… He did, he disappeared occasionally.

So then this thing was dropped into my lap because Howard had read the book and liked the dialogue and put me under contract, and I’m making this thing with Humphrey Bogart, who, you know, is my favorite actor, and William Faulkner’s already on the script. I walk in, you know, feeling about this big and I think how in the world am I going to work with Faulkner. Well, there was no problem. He greeted me courteously. He put the book down and said, “We will do alternate sections. You will do these chapters and I will do these chapters,” and so on. But that’s the way he wanted it done. He turned around and walked into his office and I never saw him again, except to say good morning. He lived behind a wall about eight feet thick. I think you could have worked with that man for ten years and never known him. He had a few close friends… He did, he disappeared occasionally.

HAMILTON: There was one story about the time they pulled him out of a gutter in Paris.

BRACKETT: Yeah. He was doing Land of the Pharaohs in Paris and went on one of these tremendous benders, and he was just a mess. He’d been rolled, beaten up, all his money, his passport, was gone. He was so upset about the whole thing he sat down for weeks and worked like a demon at the typewriter. But uh, he had a problem. But his secretary loved him. See, he was actually on loan from the studio. Now I worked for Hawks, I didn’t have to check myself in and out through the front gate. Not now, but in those days a writer came in at 9:30 and left at 5:30 and they checked you in and out and don’t take too long for lunch. But anyway, I was over in the Hawks bungalow, I came in the side gate, but Faulkner had to come in the other gate and on these days when he’d be absent his secretary would call and say, “Mr. Faulkner’s just checked in,” and everybody covered for him. He was a charming gentleman, it was just that you never got close to him.

TANGENT: Concerning your script of El Dorado and the movie Rio Bravo, was it a direct rewrite of the original script? How did that come about?

BRACKETT: El Dorado was a direct rewrite of Rio Bravo. This is a long sad story. I wrote, what was to my way of thinking, the best script I had ever done in my life. It wasn’t tragic, but it was one of those things where Wayne died at the end. I sent it out to Howard and he said he loved it, it was great, and the studio loves it, Duke loves it, it’s great. Fine. So I’m feeling all warm and happy and I go out to do the final polish on it and it turns out we’re not going to do it at all, really. And the more we got into doing Rio Bravo over again the sicker I got, because I hate doing things over again. And I kept saying to Howard I did that, and he’d say it was okay, we could do it over again.

BRACKETT: El Dorado was a direct rewrite of Rio Bravo. This is a long sad story. I wrote, what was to my way of thinking, the best script I had ever done in my life. It wasn’t tragic, but it was one of those things where Wayne died at the end. I sent it out to Howard and he said he loved it, it was great, and the studio loves it, Duke loves it, it’s great. Fine. So I’m feeling all warm and happy and I go out to do the final polish on it and it turns out we’re not going to do it at all, really. And the more we got into doing Rio Bravo over again the sicker I got, because I hate doing things over again. And I kept saying to Howard I did that, and he’d say it was okay, we could do it over again.

On one scene I said, “You did that scene. I’m not going to write those lines again.” It’s where the girl comes into town, she gets off the stage, and blah blah blah. And I said to him, “I’m not going to do it again.” And he said, “Why not? It was good once, it’ll be just as good again.” And Duke looked down at me from about eight feet high and said, “That’s right. If it was good once…it’ll be just as good again.” (Laughing) I knew I was licked right there, so all I could do was try to do it again. But, you know, the guy that signs the final check has the final say.

On one scene I said, “You did that scene. I’m not going to write those lines again.” It’s where the girl comes into town, she gets off the stage, and blah blah blah. And I said to him, “I’m not going to do it again.” And he said, “Why not? It was good once, it’ll be just as good again.” And Duke looked down at me from about eight feet high and said, “That’s right. If it was good once…it’ll be just as good again.” (Laughing) I knew I was licked right there, so all I could do was try to do it again. But, you know, the guy that signs the final check has the final say.

TANGENT: Would you tell us a little bit about the television pilot you’re doing?

BRACKETT: It’s the first science fiction job I’ve ever had in Hollywood. I don’t think that most people out there even know I write science fiction because few of them seem to read it. So this is my first time since 1944 that I’ve done science fiction…out there. This is a proposed new anthology series which will be in the general nature of The Twilight Zone, where they get somebody to host as Rod Serling was. But there will be individual stories every week, and I am doing the pilot episode. The name of the program will be called Theater of the Unknown and the name of my particular segment is called “The Day the Men Went Mad.” That was Lou Hunter’s title at NBC. I just gave them the idea. I’m supposed to have the first draft to them in early June; they’re in a hurry to get started with it, so…

TANGENT: Isn’t there a controversy concerning the fact that the anthology series seems to have higher quality, whereas the series’ with the continuing characters seem to be much more successful?

BRACKETT: Well, this is an old controversy. It’s very, very difficult to put over an anthology. In fact, I like them myself. After all, Police Story is an anthology…that does very nicely. I think they worry too much about it. If you have a good show―if the individual segments of the thing are good―I think, personally, it would draw just as well as anything else.

I hope, in this thing I’m doing, they’ll let me keep a little of the science fiction in it. They keep shying away from it, it’s too esoteric for them, they think the audience would be confused. So they want me to keep it on a more mundane level, “Let’s do some science fiction but let’s keep both feet firmly on the ground.” (Chuckling)

TANGENT: What do you have in the works now, Leigh? Besides The Reavers of Skaith.

TANGENT: What do you have in the works now, Leigh? Besides The Reavers of Skaith.

BRACKETT: I’m working on the fourth Eric John Stark novel. We finish with Skaith with this third one. Both Eric John and I have had enough with that planet, and I think we’re going to move on to something else. We’re starting a whole new world.

TANGENT: Tentative title?

BRACKETT: It doesn’t have one yet. I’m still in the feeling around stages.

TANGENT: Ed, are you working on anything right now?

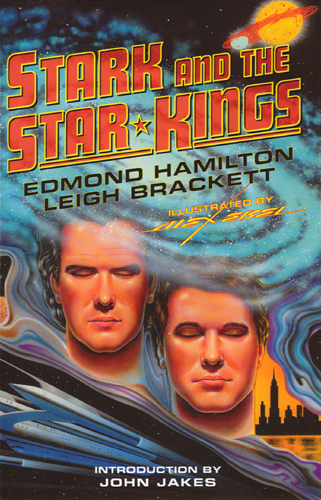

HAMILTON: Very little. I’m picking away at the beginning of a very long novel, but it’s more of an excuse to say I’m working than anything else. The fact is, I was out of the running for a couple of years with a sickness. When I was recuperating in the hospital I wrote the first half of this story with a pencil and pad. This was Harlan Ellison’s story for The Final Dangerous Visions. What he wanted was a collaboration between the two of us; you know, a formal collaboration. The story is called “Stark and the Star Kings,” and if I may say what’s funny about it: the first half of it I wrote and it’s all about Stark. She wrote the part about the Star Kings.

HAMILTON: Very little. I’m picking away at the beginning of a very long novel, but it’s more of an excuse to say I’m working than anything else. The fact is, I was out of the running for a couple of years with a sickness. When I was recuperating in the hospital I wrote the first half of this story with a pencil and pad. This was Harlan Ellison’s story for The Final Dangerous Visions. What he wanted was a collaboration between the two of us; you know, a formal collaboration. The story is called “Stark and the Star Kings,” and if I may say what’s funny about it: the first half of it I wrote and it’s all about Stark. She wrote the part about the Star Kings.

BRACKETT: He’s paid us for it, but he had some problems with his publisher. That’s what is taking the darn book so long to come out.

TANGENT: You mentioned this as your first formal collaboration. Why have you never collaborated before, in what ways were you an influence on each others work, and was there ever any feeling of competition between you?

BRACKETT: No.

HAMILTON: No, I don’t feel that. Our collaboration has been more or less unofficial in this sense…she has done more for me than I have done for her. For years I worked on comics and I had a pretty heavy schedule. When I’d be trying to do a story I’d call her on over and say, “Leigh, nobody can do a scene like this but you.” (Laughing) But I never was as fortunate as Henry Kuttner. We were out visiting Henry and Catherine at Laguna Beach, and he was telling me he’d been having a hard time doing a novel; one chapter defeated him. And he sat there at his desk all day beating his brains out and couldn’t get that chapter started, so he thought he’d go out and walk up and down the beach for several hours. The air was good but he got no ideas. So he walked wearily back to the house, got sat down, and there was the chapter, all written there beside his typewriter.

(Laughing) I love to tell that story, so then I can accuse her. Actually, that was the best chapter in the book. It was a detective novel called The Brass Ring. When I talked to him just after the novel had been published, I said, “It was a good story, Henry, but the crowning point is the chapter where the man is murdered in the dark. You get the feeling of violence and sudden death in the dark. Terrific.” He said, “Thank you. My wife wrote it.”

(Laughing) I love to tell that story, so then I can accuse her. Actually, that was the best chapter in the book. It was a detective novel called The Brass Ring. When I talked to him just after the novel had been published, I said, “It was a good story, Henry, but the crowning point is the chapter where the man is murdered in the dark. You get the feeling of violence and sudden death in the dark. Terrific.” He said, “Thank you. My wife wrote it.”

I said the same thing to Doc Lowndes up in New York years ago. He said there was one part in my Valley of Creation that was the highest point in the book. I told him the same thing, “Thank you for nothing. My wife wrote it.” She wrote just those three chapters.

TANGENT: I’d like each of you to give some thoughts on what you think of science fiction today. Gripes, feelings, trends, etc.

BRACKETT: I would hate to see the field become introverted; to see it become kind of an in joke where everybody’s using each others stuff…writing for each other, instead of the public…which can happen. I hope it will always retain that openness and freedom to move in any direction. You have new talent coming out all the time; you have new ideas, great new paths. And I think this is good. I would hate to see anything happen to it to close it in.

HAMILTON: Some years ago the late Schuyler Miller, writing in Astounding Stories I think, warned of that danger. He pointed out that the detective story had almost gotten itself into a straitjacket, the mystery story around 1930 when the rules were laid down, where things must be done this way or that way. By the late 20’s they were trying to formalize it. And then along came Chandler and Hammett and broke all the rules and gave it new life.

BRACKETT: Remember that ultimately though, the editor, whether a book has a beginning, a middle, and an end—or has none of these—will not buy it if it does not sell. That is the final word on what editors eventually do.

Remember in the 50s there was a particularly vocal group in the science fiction community that impressed all the editors in New York that science fiction had changed, it was totally different, and now it’s this and nothing else. And they tried publishing this kind of thing and the magazines died. Remember Howard Brown’s long “Folks I’m Bleeding” editorial? It was like there aren’t enough of you out there to keep the magazine going and I’ve just got to publish the stuff that sells. It eventually settles itself that way.

HAMILTON: Of course with these “revolutions” in science fiction it always comes out to about the same thing. Somebody comes along and breaks all the rules, and they’re successful at it, like Hammett and Chandler did long ago in the detective story. Ray Bradbury I think was good for the field in that sense. What he was writing was not science fiction, but it was so damn good that it had to be included in science fiction. I think you’ll always have this cycle, where somebody tries to formalize it, and becomes High Priest or Priestess of the Cult, and as you say, Leigh, it becomes an in joke. People can have a delightful time writing for each other but they lose the public. That doesn’t mean you have to pander to low taste, it just means that science fiction ought to have a thousand different doors to go through and not be confined to anybody’s idea.

BRACKETT: I suppose most of my stuff would be called escape fiction. This is the type of stuff I love to read; it got me into the field. If I were eight or nine or ten years old I don’t think I would be terribly impressed by the esoteric, heavy-thinking types of science-fiction, but…

HAMILTON: Last winter I was rereading Wells’ The Island of Dr. Moreau and I still think that was the high point of all fantasy because it succeeded on at least two different levels. It was a powerful satire. It makes Gulliver’s Travels look childish as a satire on the human race, and at the same time it’s the most terrific action story, full of suspense. And yet, if you have a narrow definition of science fiction this couldn’t possibly have been done because the science of the time was such that all these surgical wonders couldn’t have been possible, and so you would have lost a great story.

(Pointing to a fanzine with a photo in it) But this chap here, William Hope Hodgson, he had the most supreme imagination in his stories even though he had some awful faults in them. His stuff is hard to read, dreadful, and yet the world would be poorer without him, because he broke every rule–

BRACKETT: I would hate to think of a world in which there was no Worm Ourobouros.

TANGENT: So science fiction is a literature of ideas, no matter how they are expressed?

BRACKETT: I would say so. There’s room for everything.

HAMILTON: It all comes down to the poem: There are nine and ninety ways/Of constructing tribal lays/And every single one of them is right.

BRACKETT: I was just about to say that if you have some very powerful idea that is of social significance, literary significance, or any other significance, and you really must tell the story, for heaven’s sake tell it and tell it as well as you can, and make it as fine a story on all levels as you possibly can. But I dislike the idea that you can’t write anything unless you have that flag up saying Significance.

HAMILTON: Where writers seem to get caught on a dilemma in the science fiction world, is when they try to decide whether they’ll be entertainers or serious writers. Remember the monkey in Dr. Moreau that had Big Thinks? He didn’t think Small Thinks about water and game and nuts and fruit…he had Big Thinks. And when the hero came back to London and went into the church it seemed to him that the people were gabbling Big Thinks. (Chuckling) That was a cruel satire.

HAMILTON: Where writers seem to get caught on a dilemma in the science fiction world, is when they try to decide whether they’ll be entertainers or serious writers. Remember the monkey in Dr. Moreau that had Big Thinks? He didn’t think Small Thinks about water and game and nuts and fruit…he had Big Thinks. And when the hero came back to London and went into the church it seemed to him that the people were gabbling Big Thinks. (Chuckling) That was a cruel satire.

BRACKETT: I think even the most flagrant escapist fiction is not entertaining unless it makes at least an attempt to have real people in it. I mean unless you get into the emotions of the people and try to present it like something that would really happen. Like, one of the main fascinations of science fiction to me has always been the aliens. What other fields can you get into a totally alien mind, and play with all of these different worlds and social setups. One of the really great stories on alien mentality was “Saurian Valedictory” but I’ve forgotten who wrote it.

HAMILTON: Norman something-or-other was his name. It was in Tremaine’s Astounding. It was a brilliant achievement and nobody seems to have heard of it, or him. It was an attempt to depict a reptilian civilization before Man. It succeeded triumphantly; the values were all so different, the psychology. I’ve been trying to reprint that for years. I tried to get August Derleth to reprint it, but… I think I’m the only one who likes it.

BRACKETT: No you’re not. I’m the other one.

TANGENT: Are there going to be any more volumes of The Best of Planet Stories?

BRACKETT: I haven’t talked to Judy-Lynn about it lately. She said, earlier on this year, that there might be one more on toward the end of the year, but I don’t know if they’re still thinking that way or not. We’re waiting to see how the first one sold.

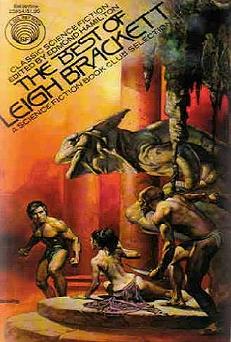

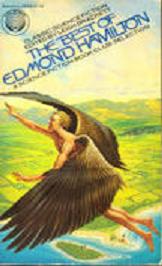

HAMILTON: We are doing the Best Of each other, however. I’m doing The Best of Leigh Brackett, the second one to come out—the reply you might call it. So she’s got to be very careful in her introduction. I’ve got the last word you see. (laughing)

HAMILTON: We are doing the Best Of each other, however. I’m doing The Best of Leigh Brackett, the second one to come out—the reply you might call it. So she’s got to be very careful in her introduction. I’ve got the last word you see. (laughing)

BRACKETT: You were asking how living and working together affected us. We almost broke up our happy home I think right after we were married. I had an order for a 40,000 word novel from Startling Stories and I said, “I think I’ve got an idea for an opening.” And he said fine. So we figured if we collaborated we could do the stories twice as fast, write twice as many, and make twice as much money. You know, which we didn’t have much of at that time. So I went out in the kitchen and pounded the typewriter and came back in with a couple of chapters and I said, “What do you think of it?” He read it, said it was great, but where do you go from here? I said, “I don’t know.” He looked at me, said, “You don’t know! This is the so-and-so bleep adjective deleted way to write a story I ever heard of!” (Laughing) He used to write the last line of the story before he’d ever write the first one.

HAMILTON: That’s just a fetish of mine. That is to say, the last word you speak to the reader, the last impression, is the last line of the story. I used to plot my adventure stories very carefully and she was just used to sitting down and writing.

BRACKETT: Right. And I would get stuck halfway through.

HAMILTON: You had a lot of unfinished stories.

BRACKETT: Yes I did.

HAMILTON: What is funny about it is that as years have gone by, she now plans her stories quite well, whereas I don’t plan at all. But that, of course, is your unconscious. That is to say, from the long decades of experience, I’ve learned to avoid the line that will lead me into a trap, so I plan it without really thinking about it.

BRACKETT: I never could plan beyond the sequence I was doing at the time.

HAMILTON: That Duvian (chuckling). I wouldn’t have been a bit surprised to get the breakfast plate in my face.

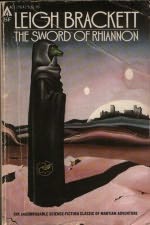

BRACKETT: This was in The Sea Kings of Mars, which was the original title of The Sword of Rhiannon. I was sailing along, and I got about halfway through the thing and I’d get two or three pages ahead and then I’d fall back and try another way, and it was one of those things where now I’d know when something’s gone wrong back in the beginning, but…I was just beating my head against the wall and finally I told Ed, “See if you can figure out what’s wrong here.” He read it and said, “Back here in chapter four you should have put in a Duvian here on the ship.” And I looked at him with this look on my face—GRRR! But he was right. That’s what hurt. I had to throw all that out and go back and do it over again.

BRACKETT: This was in The Sea Kings of Mars, which was the original title of The Sword of Rhiannon. I was sailing along, and I got about halfway through the thing and I’d get two or three pages ahead and then I’d fall back and try another way, and it was one of those things where now I’d know when something’s gone wrong back in the beginning, but…I was just beating my head against the wall and finally I told Ed, “See if you can figure out what’s wrong here.” He read it and said, “Back here in chapter four you should have put in a Duvian here on the ship.” And I looked at him with this look on my face—GRRR! But he was right. That’s what hurt. I had to throw all that out and go back and do it over again.

TANGENT: Well, how about telling Ray Bradbury hello and to come up and see you people Real Soon Now.

BRACKETT: Well, yes, I hope that Ray and Maggie would get up to see us in Lancaster. They better get that Jaguar up that freeway next time we’re out there.

HAMILTON: Ray doesn’t drive you know, he’s got the same problem I do; we both have eye trouble. The Los Angeles Times prints quite a little bit about him from time to time. He’s one of the personages of L.A. now, and they had an article about people who don’t drive that featured Ray. He goes around on his bicycle. And it’s the biggest piece of B.S. you ever read (laughing). He bought his wife a nice big 12-cylinder Jaguar and she takes him all over town. But the bicycle’s just for show.

BRACKETT: (With hands cupped toward the mike) If you’re listening Ray, he’s just kidding.

HAMILTON: He was working one time out at MGM, and he told us, “I, uh, ride down there every morning but I have great trouble—they just don’t know where to park my bicycle in the parking lot.” And Maggie looked at him and said, “That makes a nice story. I’ll add the rest of it. He rides down there because it’s all down hill, all the way. I have to go down in the station wagon and we have to put his bicycle on top of it, and I drive him back up.”

LAUGHTER FROM ALL

the end

Afterword

Tangent No. 5 included interviews with Ray Bradbury, Leigh Brackett & Edmond Hamilton, and Jack Williamson. While I had interviews yet to be published from Minicon 10 the year previous, when I looked at the above trio of interviews in the stack it became obvious that they belonged together.

Tangent No. 5 included interviews with Ray Bradbury, Leigh Brackett & Edmond Hamilton, and Jack Williamson. While I had interviews yet to be published from Minicon 10 the year previous, when I looked at the above trio of interviews in the stack it became obvious that they belonged together.

Shortly after Minicon 11 in April of 1976, and back in Oshkosh, WI, it came to my attention that the legendary, controversial, pulp magazine editor of Amazing Stories in the 1950’s, Raymond Palmer, was living in Amherst, Wisconsin, where he had converted his barn into his printing facility. Palmer was a small hunchback, having fallen off a ladder as a youth, and was responsible for the controversial (among other controversial stuff) Richard Shaver (1907-1975) stories, where Shaver claimed he had proof that an ancient civilization lived in caverns beneath the Earth, which drew scorn from diehard SF fans, yet the popularity of the stories helped save the venerable magazine from imminent extinction due to prior plummeting sales. A recluse for almost twenty years, Palmer still published and printed his small circulation UFO magazines out of his barn in Amherst.

The (late) Mark Gruenwald (one of the original Oshkosh Tangent staffers as artist; he would go on to work briefly for DC comics and Julie Schwartz in New York before his untimely death almost twelve years ago, and was also a driving force at Marvel for a number of years) and I drove to Amherst to see Palmer about his printing the next issue of Tangent. I found him quite congenial and friendly, despite the fact that these two strangers had come to see him unannounced. Following a tour of his barn/printing shop, we sat in his small, cluttered office and talked science fiction. I showed him the four previous issues of Tangent, collated and stapled by hand as they were. He offered to print 500 copies of each issue of Tangent at cost; he knew we couldn’t afford his regular rates and was giving us a break. Mark and I left Amherst that afternoon feeling ecstatic, for now Tangent would look like a real magazine, for Ray Palmer would saddle-stitch the magazine and give us much better reproduction due to the metal offset plates used, instead of the painstaking, hand-cranked mimeograph process we had been using. We were in business!

Ray Palmer did an excellent job with that Summer, No. 5 issue of Tangent. It looked terrific on all counts, including Craig W. Anderson’s cover art which many remarked favorably on. So fresh off the press with a small suitcase of Tangents, my girlfriend and I drove to Kansas City, Missouri (my hometown and birthplace) the late summer of 1976 to attend “Big Mac,” MidAmericon, the 1976 world SF convention. Chatting in the crowded lobby of the main con hotel and showing Tangent all around, and yes, selling single issues and a number of subscriptions right and left, right there in the noisy lobby, an older, well-dressed gentleman with wire-rimmed glasses turned to me and asked if he’d heard me correctly that Ray Palmer was publishing my fanzine Tangent. “No,” I replied, “He is our new printer, not the publisher.” After I explained to this man how I’d met Palmer in Amherst and visited his converted barn where he published his UFO magazines, this unknown gentleman immediately whipped out his checkbook (one of the older designs that opens horizontally) and wrote me a check for a year’s subscription. He walked away with his copy of No. 5 and I stood there with a check for $5 (each issue ran to all of $1.50 and a four-issue sub came to $5). The name on the check? SF historian and collector Sam Moskowitz. I knew who Moskowitz was, of course, but had no idea what he looked like, and to meet him like that!

Needless to say, other fans nearby who’d seen Moskowitz whip out his checkbook and buy a subscription to Tangent figured something must be up, so in short order I was surrounded and selling copies and subs to the magazine faster than you could blink an eye. Pleased and rather richer for my first meeting with Sam Moskowitz, I was elated throughout the entire worldcon at the buzz that issue generated.

Which eventually led some short time later, back home in Oshkosh, to my receiving the following letter from then SFWA President Andrew J. Offutt:

“SCIENCE FICTION WRITERS OF AMERICA

Andrew J. Offutt, President

PO Box 1

Haldeman, Kentucky 40329

Offutt to Truesdale, peace.

My Jodie [his wife, ed.] being such a loyal LoCist (loccer?) and articlist it seems to me that some 800 fanzines come in here each month. I guess it may be fewer…

When Tangent 5 came, I noticed how unusually good looking it was, how professional in appearance. And gosh, interviews with those nice people; I asked Jodie to let me see it when she had done. She put it on my desk and I didn’t get to touch it for a week. So what; I got to admire that noble cover daily!