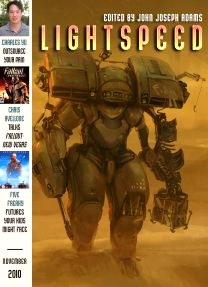

Lightspeed Magazine #6

Lightspeed Magazine #6

November 2010

“Standard Loneliness Package” by Charles Yu

“Hwang’s Billion Brilliant Daughters” by Alice Sola Kim

Reviewed by Indrapramit Das

This issue of Lightspeed has two original short stories, and two reprints, with additional nonfiction and interviews. I like their habit of including interviews with the short story writers featured; it’s a thoughtful touch. Also included is a rather beautifully rendered, if unoriginal, piece of cover artwork (again, improved by reading the artist’s insight into it).

In Charles Yu’s “Standard Loneliness Package,” an employee of a firm in Hyderabad, India, that literally outsources the emotional and physical pain of their rich clients across the globe using nebulous transference technology, struggles with an understandably taxing job, and his need for companionship. Our narrator “[rents] out his life one day at a time,” but in this future, we are told, there are people who sell their entire lives as a kind of metaphysical mortgage to help feed their families, and others who buy the assembled scraps (‘good’ leftovers from emotional outsourcing) of the lives of the more privileged as a replacement for their own. When the narrator meets a fellow employee whose father has mortgaged out his life like his own father once did, he sees an opportunity for an actual emotional connection with someone who isn’t a client.

Fascinating ideas all, to be sure, but the logistics of it all as portrayed in the story constantly confounded me—I’m still not sure how the outsourcing is supposed to work; do the clients black out while the employees in India feel their pain? Apparently not, since the employees passively experience the pain without actually controlling their clients while inside their heads. Which still leaves the question of how this actually helps the clients. Most importantly, how does one live these second-hand lives that are on sale? The narrator keeps one of these in his sights as an unattainable goal, but as a reader I couldn’t tell what this would ultimately mean for him because I didn’t get a clear picture of how it would affect his ‘real’ life. These issues get in the way because the actual experience of emotional transference and second-hand living is so central to the story and to the narrator’s plight.

The story is worth reading; it’s a nifty analog to the current trend of outsourcing sometimes unpleasant jobs to the developing world, and explores the ethical dimensions of doing so without being overtly didactic; it’s also an interesting look at a believably portrayed (though frustratingly ill-defined) future where technology has drastically affected the lives of the characters. There’s some great writing here too; the prepackaged life on sale is called a “life-loaf” and the narrator describes the experience of “the Christian God” at a funeral as “the infinite foot” on his chest. It’s a shame this skilful voice is a bit wasted on an altogether too (deliberately) distant narrator and a frustratingly perplexing conceit that would have worked really well with some clarification.

“Hwang’s Billion Brilliant Daughters” surprised me, because I’m not easily impressed by time travel tales, especially ‘quirky’ ones. But Alice Sola Kim does a good job on this one, portraying the chronologically confused travails of the eponymous Hwang with Memento-like unification of form and story. The reader experiences Hwang’s confusion as he jumps from time to time, and reality to reality. The defiantly non-linear structure is initially irritating, but builds up a nice rhythm, and becomes essential in conveying Hwang’s state of mind.

The heart of the story lies in Hwang’s relationship with his daughters, whom he meets in various different realities and timelines. The eccentricity of the various futures he visits got in the way of the poignancy that underscores the story, for me, feeling a bit too arbitrarily silly and/or weird sometimes, in Kelly Link fashion. But like in Link’s work, the dreaded ‘quirk’ isn’t enough to sink the story. The closing moments are surprisingly touching, and the imagination and humour that Kim displays in her writing are often delightful. I liked Kim’s choice of omniscient narrator, which helps the story overcome the somewhat thin characterization of Hwang and his daughters in the end.