“Break! Break! Break!” by Charlie Jane Anders

“The Mao Ghost” by Chen Qiufan, translated by Ken Liu

“How to Get Back to the Forest” by Sofia Samatar

“A Different Fate” by Kat Howard

“Phalloon the Illimitable” by Matthew Hughes

Reviewed by Martha Burns

“Break! Break! Break!” by Charlie Jane Anders is successful as a tale about the numbing effects of child abuse. Narrator Rock Manning and his best friend, Sally Hamster, have been making viral videos of Rock’s stunts, except Rock is no stuntman like his dad. The flaming bicycle he rides is real, as are the rocks Sally throws at him. It all seems reasonable to Rock since, after all, his first memory is of his dad throwing him off the roof. When Rock is finally trampled by an angry mob protesting its government, Rock senses the injustice vaguely, but still submits.

By pairing Rock’s personal tragedy with the slapstick of the videos, Anders allows us to feel for Rock without emotionally manipulating her audience. This is a huge achievement and makes the story an engrossing read. Yet when Anders uses Rock’s character to make points about propaganda, violence in media, and the role of both in social change, that effort feels tiresome.

In “The Mao Ghost” by Chen Qiufan, translated by Ken Liu, imagination subverts personal tragedy as well as the memory of political suppression. Qianer’s father may be dying of cancer or he may be turning into a cat (the word for this is “mao”). We feel deeply for the third grader and appreciate the father’s use of the fantastical to ease his child’s grief. However, as one would expect, Qiufan, has a political point to make via the double meaning of “mao.” The intelligent reader would have understand the connection without the dry history lesson Qiufan inserts in the middle of the narrative. Fortunately, it is easy to skip so that we can re-immerse ourselves in the story.

In “How to Get Back to the Forest” by Sofia Samatar, Tisha is haunted by her first summer at camp where her best friend, Cee, shows her how to vomit up the device the government uses to monitor them. Cee is a vibrant character, but of a type we’ve seen often these last few years—a mouthy teen who sees how things truly are and thereby exposes a corrupt regime.

Ultimately, how much one enjoys these tropes of recent young adult literature dictates how much one enjoys this story.

“A Different Fate” by Kat Howard is not so much a story as a meditation on the role weaving plays in mythology and fairy tales. From Penelope in The Odyssey to the heroine of “Rumplestilskin,” weaving is a way women use art to write their lives. That very promising central conceit is never developed despite a fleeting attempt to tie it to an episode of a contemporary artist who uses weaving, thus we are left with less of a story than a thesis.

Set on the day the universe becomes ruled by magic, “Phalloon the Illimitable” by Matthew Hughes chronicles the fight between two would-be wizards. The fate of everything rests on Erm Kaslo, the quick-thinking operative employed by kindly Diomedo Obron. Kaslo knows that science may have fallen to magic, but even a magician as evil as Phalloon can still fall for wine. Although fun and engaging at the outset, the length of the battle scene reduces the impact of the final comic turn.

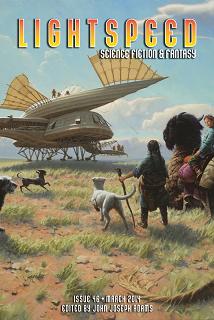

Lightspeed #46, March 2014

Lightspeed #46, March 2014