Reviewed by Aaron Bradford Starr

The word genre is being steadily blurred as people try to make higher-resolution maps of where given pieces of fiction sit in the literary cosmos. But genres are meant only to provide touchstones for the reader, a pool of general axioms so that certain conventions may be accepted as givens. But the pools of genre are deep and sometimes reveal a story to belong even if, at first glance, it appears not to.

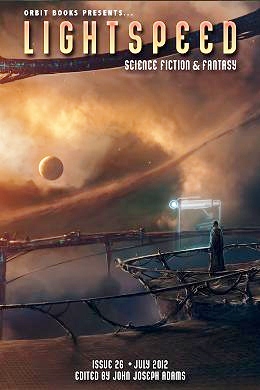

At the opposite end are stories such as those found in the July 2012 Lightspeed. Here is a collection of four short stories that hold up genre conventions, only to leave you wondering where, exactly, they belong. While each is very different, they all successfully play on the idea of giving the reader the sparest hint of even the proper genre before hurling into the story. The reason this approach works so well is that none of the four relies heavily on the genre it springs from.

“Ghost River Red,” by Aidan Doyle, is the most straightforward of the lot, giving us an alternate Japanese setting akin to the era of the Tokugawa Shogunate. Here the warrior class wields colored swords, each imbued with a different magic. Though not explicitly shown, the use of the swords give the reader the strong impression that Mr. Doyle has given a lot of thought into what each color does, but his protagonist, the swordwriter Akamiko, doesn’t take pains to demonstrate each of them. The mere fact that here is a woman who carries around an entire rack of swords makes her someone to respect.

But Akamiko is a great character in other ways. Her goal to deliver her mentor’s ashes to the cemetery at her home village brings out a steady, careful personality. Her no-nonsense approach to the ghost that is haunting the hallowed grounds where she must go is not, thankfully, a flinty-eyed descent into martial mayhem, but is rather the methodical approach that draws the other characters out. The fact that she lacks the color of blade able to affect the restless dead forces Akamiko to seek allies, and these are engaging and touching in turn.

It is easy to imagine that there are other stories of Akamiko the Swordwriter perking in Aidan Doyle’s mind, so carefully has he set this stage. But if not, “Ghost River Red” will have to satisfy the itch for a fantasy Japan, which it does.

As a direct counterpoint is “The Sweet Spot,” by A.M. Dellamonica. This tale is awash in grit, as cultural and social conventions are ground to rubble by a worldwide struggle for political dominance. Here is a science fiction tale that presents that rarest of endangered breeds: the truly alien. The Squids, as they are called, are the allies of the Democratic Forces, who are fighting the Friends of Liberation (derisively called the “Fiends” throughout the story). Liberation from what is not entirely spelled out, but alien occupation is high on the list, and the insurgent movement is gaining the upper hand.

It is this shift in power that drives the choices of Ruthie and Matt, two older teen-somethings living a hardscrabble life of refugees in their own homeland. With the entire planet engulfed in war, they get by selling oddments to the alien forces stationed in a subaquatic base off the island of Kauai. Both characters are haunted in different ways by their memory of their father, a soldier long dead that they can interact with via simulation at the cemetery where he’s been interred.

The visceral, genuinely alien presentation of the squids, along with the faceless menace of the Friends of Liberation, makes “The Sweet Spot” a rarity: a story that is successful in balancing the human and alien cultures as equals, both enmeshed in politics, emotions, selfishness and sacrifice. The final choice of Ruthie is stark, each tempting and repellant in its own way, and the resolution is truly gripping to read. Though not effortless to get into, once invested, this is a story that pays off in a big way.

“Requiem in the Key of Prose,” on the other hand, starts off seeming like a gimmick, shifting from one literary convention to another, altering points of view and style in carefully labeled segments. This would, if not handled correctly, come off as silly. And yet Jake Kerr uses it to such great effect that, while reading it, it’s easy to wonder why all writing isn’t done this way. The shifting viewpoint and upfront descriptive passages allow the reader to learn everything that they need to know, embracing, at times, questionable writing technique because we’re told in advance that this section will be passive voice, this next something else. But the shift always takes the story forward, skipping over all manner of backstory and detail in a manner that grows necessary to tell the tale.

The details of the story, of a world crippled by environmental disaster, are like the subject of an impressionistic painting: secondary to the quality of the execution. The main characters, Adam and Violet, are patches of vivid color, snippets of clarity that are replaced by others as the story dives forward. A simple breakdown in machinery brings to light a massive breakdown in human forethought, and the cost of the repair ripples forward, through multiple tenses and angles, to reveal something larger about people, and what they mean to each other.

Just as A.M. Dellamonica did with “The Sweet Spot,” in presenting aliens that actually seem like aliens, Maria Dahvana Headley gives us magic that truly feels like magic. “Give Her Honey When You Hear Her Scream” is all about the inexplicable nature of magic, including the literary magic of true love. The ill-fated yet predestined meeting of two lovers sparks the magic-laden fury of their significant others. A revenge is called for, the two agree, and the form of it is hinted at in the opening paragraphs.

The magic of the story is straightforward, yet is so colorful and reality-warping that it is instantly credible. It embraces every trope of the magician, every cliché of the witch, and runs with them. The magician and the witch are both self-absorbed and self-conscious, and this makes their great power dangerous. It isn’t cool actually, in any normally expected sense, and the fact of this makes the silliness feel sinister. But in the end, the silliness drops away, and we are left with only the sinister, the clever, and the original. If the story is overwritten in places, it is a small fault, given the immensely original denouement.

The pure love of the nameless couple is not the heart of the story, of course. The real tale is the twisted, jilted magician and witch they hope to leave behind. It is the flawed self-conceptions and towering egos of this second pair that drive the story forward, and their relationship that is the true catalyst. Their pain is the monster introduced in the opening paragraphs, revealed, at the end, in all its demented glory.