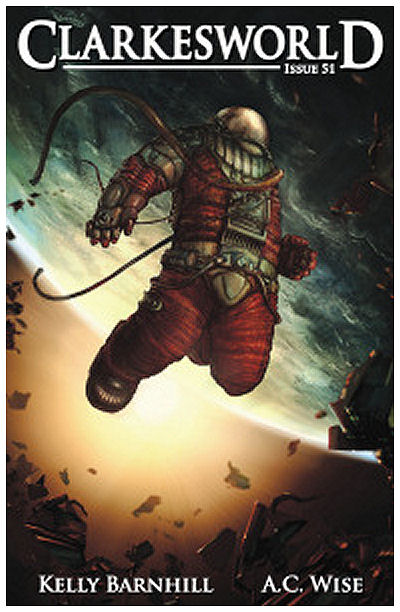

Clarkesworld #51, December 2010

Clarkesworld #51, December 2010

“The Taxidermist’s Other Wife” by Kelly Barnhill

“The Children of Main Street” by A.C. Wise

Reviewed by Indrapramit Das

Kelly Barnhill’s “The Taxidermist’s Other Wife” is a beautifully written story that stands in that no-man’s-land between genre and literary fiction, where writers can experiment with both without sticking too closely to the rules of either side. I applaud cross-genre pollination, and think there’s much potential in marketing such work, though I sometimes lament the vagueness that plagues some stories of this ilk, whereas the writer seems unable to deliver either a good literary fiction story or a good genre story.

Barnhill manages admirably to walk the line without sacrificing too much to bend down at the altar of the “literary” world. Her stylistic choices seem organic to the tale, rather than simply pretentious or overdone. The story itself follows the viewpoint of a town’s populace (it’s written in the rarely used first-person plural) as they come to terms with the strange ways in which their Mayor, the eponymous Taxidermist, deals with the death of his popular and much-loved first wife. Put “taxidermy” and “other wife” together and you’ll get somewhat of an idea of where this story is going, but thankfully not enough—Barnhill does some interesting things with notions of loss and prelapsarian preservation, and the sterility of human monuments (both figurative and literal).

Her language alone is reason enough to read the story. There are some striking passages here:

“Night falls early in November. In those waning moments of light, the sky paints its face like a harlot (overripe rouge, stained lips, unbuttoned taffeta spreading outwards like wings), before opening itself wide to the void of space. Each jagged shard of light in the darkness is a tiny message sent from the recesses of time. ‘You are alone,’ the stars say. ‘You are alone. You are still alone.’”

The collective viewpoint is interesting, bringing to the mind the dreamy beauty of Jeffrey Eugenides’ The Virgin Suicides, but it also suffers from a similar problem to that novel, in that the perspective of the story elides any opportunity for deep characterization or empathy, leaving the tale too distant and overly allegorical for my tastes. Furthermore, the conclusion alters the attitude of the townspeople rather drastically, in a move that I couldn’t quite make sense of. Still, Barnhill does evoke the personality of the Mayor/Taxidermist quite well, and create a character out of the decaying town itself.

A.C. Wise’s “The Children of Main Street” sticks closer to science fiction than Barnhill’s story, though its lack of attention to the setting and science-fictional premise reveals a similar aspiration to the literary short, or the blending thereof with genre.

Just to clarify, when I talk of literary fiction, I don’t mean to indicate that science-fiction and fantasy, or “speculative fiction” works can’t be great literature (quite the contrary); I’m merely dealing in the terms that marketing has dealt us. I’m referring to literary fiction and genre fiction as two categories of literature, not assigning values to either. To get back to the point, Wise writes her science fiction tale in a way that gives the impression of a writer trying for a literary short that rather hurriedly uses science fiction concepts rather like fantasy elements in magical realism, rather than crafting well-thought-out science-fiction with literary themes, if that makes any sense.

The story follows three characters—all parents in a colony on an alien planet where human children have begun spontaneously changing sex (the story uses the more ambiguous term “gender”) at will. A great premise, to be sure, and ripe for exploration (and most famously explored, perhaps, by Ursula K. LeGuin). Wise doesn’t exploit it as well as I hoped after a well-written opening that establishes the setting and idea. The parents react to the sex-changing phenomenon, as one would expect, quite strongly—and Wise shows them reacting in logical and dramatically sound ways that form a solid story arc. But it all felt somewhat preset and dry to me; as if Wise had mapped these characters, and the story, out in her head, but not given it enough time to develop properly into something real on the page. I wanted to be there on that colony, and empathize with the characters, but couldn’t.