Exhuming “They’d Rather Be Right”

by

Manjula Menon

∞ ∞ ∞

They’d Rather Be Right, by Mark Clifton and Frank Riley, beat out numerous heavyweight contenders including Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings for the 1955 best novel Hugo. The flaws in the novel have been discussed in skilled detail by others and I will not repeat them here. Instead, my aim is to rekindle a gentle spark of interest in the work.

They’d Rather Be Right unfolds in San Francisco at “the turn of the century.” It is a fraught and dystopian time, one in which new ideas, particularly those that challenge the status quo, are censored and penalized by the oppressive government via “opinion control”: “Now, for almost half a century, there had been nothing new … There was still enough gadgetry invention to confound any criticism. But there was no exploration of new areas, hunting for new frontiers.”

Bossy, the first “synthetic brain,” has been created in stealth on a university campus. Rumors begin to circulate when news of Bossy’s existence leaks to the public: “Bossy could take over any job and do it better than a man. Bossy could replace even management and boards of directors. Bossy’s decisions would be accurate, her judgment unclouded by personal tensions.” Bossy, in the words of one character, might even make “slaves of all the people and take over the world” or “wipe humans off the face of the earth.”

The concern of machines overtaking and supplanting humans is a current one. As in They’d Rather Be Right, the story’s epicenter is San Francisco. As in They’d Rather Be Right, many fear that the immense strides made in the fields of machine learning and artificial neural networks could leave humanity teetering on the precipice of a dangerous new era. Real world discussions mirror those in the novel: What if the technology, one that has demonstrated exponential improvement year after year, falls into the wrong hands? Or even the right ones? The road to hell, as the saying goes, is paved with good intentions. Current proponents argue that the very same complaints were made about every new technology from automobiles to computers. As the Buggles sang in their 1979 hit, Video Killed the Radio Star, “we can’t rewind, we’ve gone too far.”

Back in the world of the novel, the stakes are raised when we learn that Bossy can rejuvenate cells and confer immortality: “Death was conquered. Age was conquered. Now perpetually young and happy people could live forever in this best of possible worlds.” The question of who would get to be immortal, and who would not, became top of mind. If Bossy conferred immortality to only the rich and powerful, there was a real possibility that society would collapse: “… the consolation of the stupid, the ignorant, the moronic, the vicious, everybody—is that death gets us all. It’s the big equalizer. That’s the time when the little man is just as important as the big man. They’re not going to like it when they realize they’ve been robbed of that one great satisfaction; that they won’t be able to get even, after all.” A belief quickly spreads among the public that only 5% of the world’s population was worthy of immortality, with most also believing that they themselves were part of that 5%. What if there was a way to confer immortality to anyone worthy of it?

In the real world, cell rejuvenation is not a new phenomenon. In 1931, the Swiss physician Paul Niehans successfully treated a patient whose parathyroid glands had been erroneously removed. Niehans injected her with the mushed up parathyroid glands of a steer, effectuating her complete recovery. Niehans later controversially moved on to transplant embryonic sheep cells into humans in an attempt to treat other diseases. Current cellular therapies usually involve transplanting healthy human cells in order to trigger a salutary response in diseased tissue or cells. Take stem cells, for example, which are those cells that can differentiate multi-directionally into any of the over 200 specialized cells in the human body. Mesenchymal stem cells are regularly transplanted to repair damaged bone or cartilage. Hematopoietic stem cells are routinely transplanted to help repair blood cancers and other blood related diseases. Lymphocytic stem cells are transplanted to aid the adaptive immune system find and eliminate pathogens or mutations.

Cellular and gene therapies are also an active area of research in the field of longevity. For example, a recent study showed that that it was possible to edit cellular epigenetic information to speed up or reverse the effect of aging in mice. Another study showed senolytic cells successfully used as a prophylactic against aging in mice. Studies like these make it at least conceivable that a successful cell “rejuvenation” type therapy could one day raise the same questions in the real world as those posed by the novel.

In the novel, the cellular rejuvenation technology that Bossy uses to confer immortality is of the very different “psychosomatic” kind: “Most of the psychologists work with some mysterious thing they call mind. The psychosomatic men work directly with the body cells. Not only in the brain but all over the body, each cell seems to have a mind and memory of its own. Each one is capable of getting its own twists of inhibitions and repressions. The idea is to go clear down to the cellular level and take the load off of each cell so it can stretch and grow and function again.”

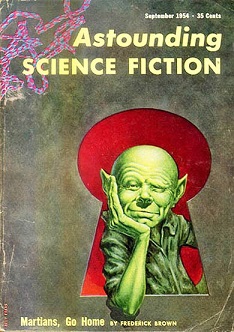

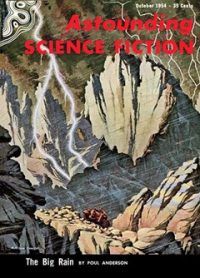

They’d Rather Be Right was serialized in Astounding Science Fiction in the early 1950s (August-November 1954), at a time when its legendary editor John. W. Campbell was at its helm. Campbell, who had become heavily invested in the reality of “psi”, or paranormal and psychic phenomena, had been publishing stories featuring “psionics” in Astounding. Psi phenomena is to psionics, what electromagnetic phenomena is to electronics: in the world of the novel, psi, like electromagnetism, could be harnessed and engineered into mass-produced products.

In the West, belief in the existence of psychic phenomena has been around since at least classical antiquity; few important decisions were made in Greece at the time without consulting the Sibyl of Delphi, for example. Nineteenth century scholars reinvigorated interest in the study of psychic phenomena by applying empirical and scientific methods to it. The American Society of Psychical Research was cofounded by the eminent psychologist William James in 1884, Stanford became the first American university to conduct research in the field in 1911, and in 1937, The Journal of Parapsychology, an academic, peer reviewed publication from The Duke University Parapsychology Lab, began to publish psychic research that used statistical techniques from psychology and medicine. Although scholarly interest in psi and parapsychology waned in the decades that followed, it never ceased. In 2011, for example, The Journal of Personality and Social Psychology published “Feeling the future: Experimental evidence for anomalous retroactive influences on cognition and affect” by Cornell University psychologist, Daryl Bem: “This article reports 9 experiments, involving more than 1,000 participants… all but one of the experiments yielded statistically significant results …” When Bem’s precognition experiments failed to replicate, the blowback spread to other subjects that used the same methodologies; the paper is often credited with kicking off the ongoing “replication crisis” in the fields of psychology and medicine. The crisis of replication has not stopped psychology or medical journals from continuing to publish findings, and neither has it deterred the remaining parapsychologists working in academia. As in They’d Rather Be Right, the proponents of psychic phenomena yet believe that they will build a device or conduct an experiment that will definitively establish the reality of psi.

The novel’s main character is the 22-year-old lonely telepath, Joe Carter. The novel repeatedly laments the lack of vocabulary to describe how Joe’s psi-ability works: “For communication implies shared comprehension. It was not only that they lacked vocabulary—they did not even know they lacked it. To a race of totally deaf would the musical instrument and the complex art of music develop?” Joe can send telepathic inquiries in the form of expanding psi-fields. Joe’s regular hearing is overlaid with the “esper hum of half vocalized words and phrases picked up from the minds of the people all about the area.” Joe can psionically “penetrate” and “probe” minds to get both somatic and psychic information; he can feel the bodily sensations of others as well as deeper level thoughts and emotions. Joe can perceive with his eyes and his psi-sight. Joe can set up “protecting wave fields” or “wave fields of illusion” that prevent those outside the field from hearing or seeing anything within. Joe’s spine tingles when his psionic sense picks up danger.

In the novel, the field of “psychosomatics” is an established one, with medical doctors who specialize in the field. However, nobody believes that telepathy is possible. It was Joe, rather than the two psychosomatic professors credited with it, who had been the creative force behind Bossy. Joe’s hope is that Bossy will deliver him from loneliness: “From the machine, in due course, a man or a woman would emerge—a real man or woman; not the twisted, warped, pitiful deformity which passes as human.”

It was soon discovered that Bossy’s psychosomatic cellular rejuvenation technique could only heal the body if the mind did not stand in the way. To gain immortality, a person had to be able to give up all their cognitive prejudices, including everything they had thought they knew about how the world worked and why. One of the scientists who helped create Bossy fails to give up his cognitive biases and thus fails to become immortal. Were the cognitive biases blocking his rejuvenation related to the scientific dogma against the existence of psychic phenomena? This is a novel with a point of view. There is a “humanist” quality to the novel in the 18th century sense of the word; its aim is not merely to entertain or even edify, but to wield literary eloquence and craftsmanship in order to persuade. Embrace radical new ideas, the novel argues, even ones that run contrary to everything you believe, and you too might get to live forever.

Indeed, Bossy manages to successfully rejuvenate only two people by the end of the novel, both long-time residents of the Tenderloin: Mabel, a Tenderloin landlord with a heart of gold, and Carney, a one-time carnival mentalist. There is a hard-boiled edge to the novel, reminiscent of the works of Dashiell Hammett. We learn that Mabel and Carney are successfully rejuvenated because their experience living, and in Mabel’s case, thriving in society’s edges has taught them to be pliable about pretty much everything. It is this pliability of mind that allows Bossy to not only reverse aging but to also radically upgrade their rationality and intelligence. The novel attributes Mabel’s successful rejuvenation to her previous status as a “hundred-dollars-a-night girl.” It is implied that “respectable” women would, alas, likely not qualify for Bossy style cellular rejuvenation and immortality. To Joe’s tremendous gratification, the therapy also turns them into telepaths. Joe is no longer alone. Mabel becomes Joe’s romantic partner and Carney, a trusted friend.

While the psionic technology described in the novel has never come to fruition in real life, brain-machine-interfaces (BMIs) already allow for the command of machines through thought alone. Modern BMIs use a web of nanoscale, Wi-Fi enabled electrodes that are embedded into the brain. With the help of an artificial neural network and a language model, signals from these kind of cortically embedded arrays have accurately decoded neuronal signals into words at almost 80 words per minute and with about a 75% accuracy rate. Optical methods have also successfully been used to precisely stimulate and control the individual neurons of mice, with far less transduction as compared to electrical counterparts. It is at least conceivable that we might one day be able to greatly enhance our cognitive abilities and to communicate with each other even telepathically.

The San Francisco of the novel might feel familiar to those who know the current city. The Tenderloin, for example, is described thus: “He steeled himself against the somatic effects of dejection and misery, and sampled the minds of those men still out on the street. Some of the men were drunk; others, lacking the price of a flop house, were drugged with weariness and lack of sleep. A pair of cops were working the street two blocks up, routing such men out of doorways or alley corners where they were trying to sleep.”

Indeed, Joe himself is a recognizably modern-day San Francisco resident. Joe is talented and ambitious to change the world. As he paces the streets of the city, “He knows his debt for all the things civilization has given him, and he feels an overwhelming obligation to repay that debt. He must strive to lift man from his despair and purposelessness into realms of great achievement, enlightenment. Nothing less would be good enough for mankind.” Decades before Silicon Valley made the city famous for its technology, They’d Rather Be Right had already imagined it so.

As for the topical question of who should control artificial super-intelligence, the novel accords an unequivocal answer: everyone; Bossy is replicated by the millions and shipped to whoever wants a copy. Anyone could become immortal, but not if they’d rather be right.

External Links:

Reprogramming to recover youthful epigenetic information and restore vision | Nature

The year of brain–computer interfaces

https://neuralink.com/patient-registry/

https://library.duke.edu/exhibits/2020/parapsychology

[Astounding Science Fiction, Aug.-Nov. 1954 serializing They’d Rather Be Right]

Manjula Menon’s most recent publications are the essays, Science Fiction and The Shaping of Belief, and Truth Embedded in a Tale, both in Sci Phi Journal.

Manjula Menon’s most recent publications are the essays, Science Fiction and The Shaping of Belief, and Truth Embedded in a Tale, both in Sci Phi Journal.

Her fiction has appeared in Nimrod International Journal, North American Review, Santa Monica Review, Pleiades, Southern Humanities Review, and Tampa Review, among others. A speculative story/recipe was included in the collection of fantastical mixology, Strange Libations: Dark Cocktails from the editors of Apex Magazine. Her awards include a Yaddo Fellowship, a Breadloaf Writers Conference “waitership”, and a fellowship from Writing Downtown in Las Vegas.

Menon has degrees in astrophysics and electrical engineering, and has an abiding interest in philosophy. She’s been part of the founding teams of two technology start-ups, worked for a big New York City consulting firm, and spent years designing and building cellular networks in South Korea, Italy, Belgium, and elsewhere. Her technical publications include a paper evaluating code division multiplex access (CDMA) for microcell applications available in the IEEE Xplore digital library.

Menon has also co-produced a short film, Sculpture 1, about an unlikely relationship that develops between two people in a small “figurative arts academy” in New York City. Menon was born in India, and spent part of her childhood in Zambia. She lives in San Francisco.

All text copyright © 2024 Manjula Menon

All Rights Reserved.