by

George Allan England

by Dave Truesdale

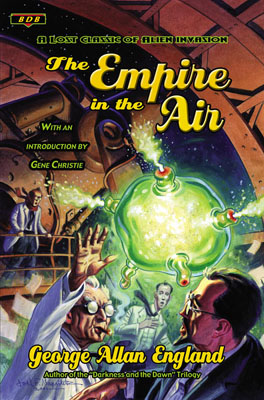

The Empire in the Air was first serialized in All-Story Cavalier Weekly in its November 14th, 21st, 28th, and December 5th, 1914 issues. In 2006 Tom Roberts and his Black Dog Books published it in book form for the first time since its magazine appearance; in 2006 over 90 years ago, and now in 2012 almost 100 years ago.

George Allan England (1877-1936) was born the son of an Army officer on a military base in Nebraska (the same base at which George Armstrong Custer was stationed, Custer’s Last Stand taking place in 1876) and traveled widely. A graduate of Harvard University, England’s exploits as a world-traveled explorer and treasure hunter helped form the colorful locales and adventures he incorporated into his approximately 14 novels and equal number of short stories. As Gene Christie notes in his informative introduction, England’s most inspired work came in the decade 1909-1919, in which The Empire in the Air is solidly anchored.

A staunch, some might say even radical socialist, England ran unsuccessfully as the socialist candidate for Governor of Maine in 1912, and his socialist philosophy infuses many of his stories and novels. The Empire in the Air, however, shows no evidence of his political leanings, and can be read as an engaging, imaginative alien invasion novel of the sort we might categorize today as super-science.

The story takes place in the Boston-Cambridge, Massachusetts area where aviator Paul Kramer attempts to set a new world altitude record in his little monoplane as the assembled crowd, including his lady friend Ethel Stockton, watch. As he flies higher and higher and breaks the previous record of 19,500 feet, his plane suddenly vanishes from the instruments scientists are using to track him from the Observatory in Boston. Ethel, overcome, faints and falls into a coma.

Unbeknownst to those on the ground, Kramer has been captured, transported into the Fourth Dimension, where exist an alien race bent on invading and destroying Earth. The invaders appear as green globes, pulsating and shimmering, able to float through solid objects, and through his wiles while trapped in the Fourth Dimension (Time runs at a different pace there) Kramer is able to send messages through them to the scientists at the Observatory. At one point he is even able to speak in his own voice through his entranced girlfriend Ethel, warning of the imminent danger.

The problem arises when at first no one believes Kramer’s messages, even as the mysterious aliens–by the millions–begin appearing all over the planet and destruction of major cities is taking place, leaving Earth in confusion and world-wide panic. Soon, however, the few scientists along with Kramer’s friends working on the problem have no recourse but to believe Kramer’s urgent pleadings of coming doom and frantically begin to follow his instructions to the letter, for time is growing short before the final alien assault on Earth.

As Gene Christie points out in his introduction, Kramer’s plan for defeating the aliens from the Fourth Dimension is strangely reminiscent of the solution to defeating the aliens in the film Independence Day some 80 years later. To wit: Kramer instructs that as many flyers as possible fly to 20,000 feet where they will be transported to the Fourth Dimension, where Kramer will lead them in a do-or-die war against the aliens on their home ground. Needless to say, Kramer and his brave fellow aviators defeat the threat, save Earth, and Kramer and his loving Ethel (now awake) are reunited in bliss.

While many of the stories in the pulp magazines around the turn of the 19th century were banged out faster than the speed of light and read like it, England’s prose is more polished and the contemporary reader will have no trouble enjoying its period phrasing and terminology, quaint as some of it is. This is part of its charm, not to mention the energy with which the story is told. The description of Kramer’s time spent in the Fourth Dimension at the beginning of the tale is rife with an otherworldly sense-of-wonder and pages are turned quickly. The tension mounts from there in chapter after chapter as the unimaginable events become reality to those attempting to come to grips with the problem, accept it for all its improbabilities, then put their doubts aside and their wits in high gear if Earth is to be saved in time. And England leaves no doubt here that it is an unflagging belief in science and its power that will eventually defeat the alien threat, sending them in abject defeat back “beyond the Galactic Rim.” Which science does, with Kramer’s knowledge of, and assistance from the Fourth Dimension, which Earth scientists then must figure out how to turn against the scientifically advanced invaders using only the science they know at the time.

George Allan England’s The Empire in the Air, at just under 200 pages of easily readable type (Christie’s introduction brings the book in at 206 pp.), is a dandy read, infused with wild imaginings and theoretical science, wrapped in a taut thriller of alien invasion, how Mankind wins the day with brave souls in souped-up monoplanes, and an over-arching faith in science which proves true to the cause. And, of course, the hero gets the girl.

Can you imagine a more rousing tale for the audience of the time than a daring aviator out to break the world altitude record only to be thrust into the Fourth Dimension–a scarce decade after the Wright Brothers skimmed the ground at Kitty Hawk?

While England’s most acclaimed work is the Darkness and Dawn trilogy (written just before Empire during the years 1912-13), it is to Black Dog Books publisher Tom Roberts’ immense credit that he has given us this all-but-forgotten flight of scientific fancy, heretofore unpublished in book form since its magazine serialization nearly 100 years ago.

A rear cover quote from noted SF historian and anthologist Mike Ashley pretty well sums up this sadly overlooked work: “George Allan England’s masterpiece stands as one of the great prototypes of modern science-fiction.” And the late, early-SF historian and anthologist Sam Moskowitz echoes Ashley’s sentiment when he says: “A super-science epic…ahead of its time.”

For those who enjoy a page-turning, plot-oriented story filled with danger and high adventure regardless of genre, I recommend this novel. For SF insiders who appreciate the history of the genre, have read widely, but who wish to close gaps in their knowledge of seminal pre-genre works, then this book is for you as well.

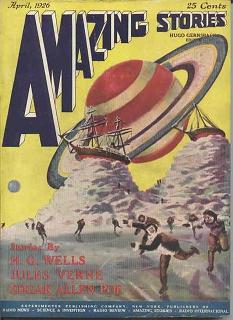

(Incidentally, one of England’s relatively few short stories “The Thing From — Outside!,” first published in Hugo Gernsback’s Science and Invention in 1923, also saw print in Gernsback’s Amazing Stories for April 1926, well known today as the first issue of the very first science fiction magazine.)