Mike Ashley is the science fiction, fantasy, and mystery genres foremost bibliographer. He is perhaps most widely and popularly known for the thirty-plus volumes of his MAMMOTH BOOK OF series, a few examples of which are THE MAMMOTH BOOK OF SHORT HORROR NOVELS (1988), THE MAMMOTH BOOK OF NEW SHERLOCK HOLMES ADVENTURES (1997), THE MAMMOTH BOOK OF SCIENCE FICTION (2002), THE MAMMOTH BOOK OF EXTREME FANTASY (2008), and THE MAMMOTH BOOK OF TIME TRAVEL SF (2013).

He was honored with an Edgar for his 2002 work The Mammoth Encyclopedia of Modern Crime Fiction.

Of equal popularity and interest to science-fiction fans is Mike’s ongoing History of the Science Fiction Magazines, from Liverpool University Press, which will run to five volumes. Part one The Time Machines (2000), covered the years 1926-50, part two, Transformations (2005), covered 1951-70, and part three, Gateways to Forever (2007), covered 1971-80.

Mike has written over 100 books, ranging from various subjects in the reference field, to work in both the anthology and single author collection realm, including a handful of historical collections surrounding the legend of King Arthur.

I wish to express my sincere thanks to Mike for graciously allowing Tangent Online to run the article below. When asked what upcoming work he had in the pipeline, he replied:

“I have recently completed Volume 4 of my history of the science fiction magazines, called SCIENCE FICTION REBELS, to be published by Liverpool University Press later this year. This volume covers the 1980s. I also have an anthology out from Dover Books, THE FEMININE FUTURE, which looks at the early contribution by women writers to science fiction from the 1870s to 1930.”

Born in 1948, Mike Ashley resides in Chatham, Kent, England.

♣ ♣ ♣

THE BIGGEST PULPS

By Mike Ashley

Have you ever wondered what the largest pulp magazine was? I don’t mean in dimensions, but in the number of pages and total wordage.

Have you ever wondered what the largest pulp magazine was? I don’t mean in dimensions, but in the number of pages and total wordage.

When I began collecting pulps the cheapest I could find tended to also be the smallest and I got used to pulps of 128 or 112 or even 96 pages. The pulps that ran to 144 or 160 pages struck me as huge, even though for much of the life of the pulps this was pretty much the standard size. With around 600 words on each page, once you allow for illustrations and editorial matter you could easily be looking at 80,000 words an issue, up to 100,000 words in some. But then it dawned on me that 144 or 160 was in itself a reduction from the great days of the pulps.

As we know, magazines are bound in signatures usually of sixteen pages so that an issue’s pagination will usually increase or decrease by that amount. Sometimes special pages are bound which may make a difference of four or eight pages, but as they usually apply to either adverts or pictorial matter they can be ignored for these purposes. My interest is in how much text you got for ten or twenty cents. So, after 160, pagination would increase to 176, 192, 208, 224, 240 and so on.

In some ways it was Munsey’s Argosy that set the benchmark. When he converted it into an all-fiction magazine in October 1896 (cover at left), and into a fully-fledged pulp in December 1896, the magazine boasted 192 pages: all for ten cents. So one cent bought 19.2 pages. I’ve never actually counted the wordage in those early Argosys and it’s an exercise that needs doing to make the following analysis accurate. In his anthology Under the Moons of Mars, Sam Moskowitz states that each issue carried 135,000 words of fiction (p. 308), which is around 700 words per page. On that basis, one cent was buying 13,500 words, or a decent size novelette.

In some ways it was Munsey’s Argosy that set the benchmark. When he converted it into an all-fiction magazine in October 1896 (cover at left), and into a fully-fledged pulp in December 1896, the magazine boasted 192 pages: all for ten cents. So one cent bought 19.2 pages. I’ve never actually counted the wordage in those early Argosys and it’s an exercise that needs doing to make the following analysis accurate. In his anthology Under the Moons of Mars, Sam Moskowitz states that each issue carried 135,000 words of fiction (p. 308), which is around 700 words per page. On that basis, one cent was buying 13,500 words, or a decent size novelette.

Once Street & Smith got in on the act they naturally had to outdo Munsey. The Popular Magazine was launched in November 1903 as a boys’ magazine but in February 1904 converted into a pulp magazine and added an extra leaf to make 194 pages so that it could proclaim itself “The Biggest Magazine in the World.” Allowing for the adverts those extra two pages didn’t make any difference. What’s more The Popular used a slightly larger typeface and had increased margins so the wordage was less. Moskowitz estimates it at 126,000 words, so that one cent bought 12,600 words.

The success of The Popular allowed Street & Smith to be more daring. From December 1906 the page count increased to 224, but with a corresponding increase in price to 15 cents (March 1907 cover at right). This meant that one cent bought only 15 pages or 9,800 words. So whilst it was the world’s “biggest magazine” it didn’t provide quantity for cash. But it probably provided quality, because circulation rose.

The success of The Popular allowed Street & Smith to be more daring. From December 1906 the page count increased to 224, but with a corresponding increase in price to 15 cents (March 1907 cover at right). This meant that one cent bought only 15 pages or 9,800 words. So whilst it was the world’s “biggest magazine” it didn’t provide quantity for cash. But it probably provided quality, because circulation rose.

As other all-fiction pulps began, the standard size and price was 192 pages for 10 cents. This was true of All-Story Magazine, The People’s Magazine, The Railroad’s Magazine and The Scrap Book. However The Scrap Book conducted a bold experiment which causes confusion. From July 1907 it became two magazines in one – or rather it was issued in two halves. The first half was a general interest magazine, illustrated on coated stock, whilst the second half was the all-fiction pulp. In total they ran to 180 +192 pages, or 372 pages, but the whole package cost 25 cents, or just under 15 cents a page. I’ve no idea what the total wordage was in these dual issues, but I would estimate about 250,000, so one cent bought 10,000 words. These figures were about the same as the enlarged Popular but not as good as The Argosy or the other 192-page 10-cent magazines. What’s more they were issued in two separate sections, not bound as one magazine, so although you bought 372 pages in one go, it was not in one single binding.

My emphasis is on pulps, but let’s just turn aside for a moment and consider the general interest glossy magazines. These were supported by advertising and their enhanced circulation meant they could boast many pages of adverts. One could judge the success of a magazine by the size of its commercial section. Munsey’s, for instance, carried up to 120 pages of adverts on occasions. I believe the record was held by Hampton’s Magazine which, by December 1910 (cover at left), was running 130 pages of adverts on top of the 182 magazine pages. So you could argue that Hampton’s was the first single magazine to exceed 300 pages, coming in at 312. It looked big and bulky on the stands, selling for fifteen cents or, in theory, 20.8 pages per cent, but no one regarded the adverts as part of the magazine. What’s more they weren’t included in the bound volumes, so despite its bulk, Hampton’s was really a 182-page magazine in a thick coat, and readers weren’t getting anything extra for their money.

My emphasis is on pulps, but let’s just turn aside for a moment and consider the general interest glossy magazines. These were supported by advertising and their enhanced circulation meant they could boast many pages of adverts. One could judge the success of a magazine by the size of its commercial section. Munsey’s, for instance, carried up to 120 pages of adverts on occasions. I believe the record was held by Hampton’s Magazine which, by December 1910 (cover at left), was running 130 pages of adverts on top of the 182 magazine pages. So you could argue that Hampton’s was the first single magazine to exceed 300 pages, coming in at 312. It looked big and bulky on the stands, selling for fifteen cents or, in theory, 20.8 pages per cent, but no one regarded the adverts as part of the magazine. What’s more they weren’t included in the bound volumes, so despite its bulk, Hampton’s was really a 182-page magazine in a thick coat, and readers weren’t getting anything extra for their money.

One of the features of the pulps, especially as time progressed, was their lack of adverts. The more prosperous, like Blue Book, ran an advertising section, but even this vanished in time. So we can ignore the bulky advert-laden glossies and return to the quest for the biggest single pulp.

One of the features of the pulps, especially as time progressed, was their lack of adverts. The more prosperous, like Blue Book, ran an advertising section, but even this vanished in time. So we can ignore the bulky advert-laden glossies and return to the quest for the biggest single pulp.

The Popular remained 224 pages (sometimes 228) until the end of 1917 when it dropped to 192. In that last year the price had risen to 20 cents, so its price per page was rising. Adventure was also 224 pages, as was Blue Book, though Blue Book briefly increased to 240 pages from October 1914 (cover at right) to at least February 1917, but kept the 15¢ cover price, thus providing 16 extra pages and 9,600 words per cent.

Let’s step aside again and consider the “bedsheet” issues. When Amazing Stories started in April 1926 it was published in the same large-size format as Gernsback’s other technical magazines. Gernsback had acquired special new paper called “bulky weave,” so that its 96 pages looked almost as thick as the standard pulps. Selling for 25¢, Amazing doesn’t look much on the value scale, coming in at only 3.8 pages per cent, but we have to take into account Amazing’s extra page size and the likely increase in wordage. When I did a calculation some years back I assessed the large-size Amazing ran about 750 words a page, though of course this average reduced with the number of illustrations. Overall Amazing offered about 70,000 words, far less than the standard pulps and equating to only 2,800 words a cent.

Neither was this much better with Amazing Stories Quarterly. Although this ran to 144 large-size pages, it cost 50¢, equating to under 2.9 pages per cent, or 2,100 words per cent. Big and bulky it may have looked, but the general pulps gave much more.

Of course when Ziff-Davis took over Amazing Stories in 1938, Ray Palmer made it popular and profitable and in May 1941 it increased its pagination from 148 to 244, with a price rise from 20¢ to 25¢. This was a one-off experiment, but it became permanent from January 1942, and increased again to 276 pages from April 1942 (May 1942 cover at left). This only lasted for six issues, but for those six issues Amazing was the biggest pulp around, offering 11.04 pages per cent. (Mammoth Detective kept the 276 pages for longer, until 1945, and Mammoth Mystery’s first few issues also sported 276.)

Of course when Ziff-Davis took over Amazing Stories in 1938, Ray Palmer made it popular and profitable and in May 1941 it increased its pagination from 148 to 244, with a price rise from 20¢ to 25¢. This was a one-off experiment, but it became permanent from January 1942, and increased again to 276 pages from April 1942 (May 1942 cover at left). This only lasted for six issues, but for those six issues Amazing was the biggest pulp around, offering 11.04 pages per cent. (Mammoth Detective kept the 276 pages for longer, until 1945, and Mammoth Mystery’s first few issues also sported 276.)

As an aside, it’s worth remembering that unsold issues of Amazing (and its companion Fantastic Adventures) were reissued in sets of three as a quarterly, selling for 50¢. The Winter 1942 rebound Amazing Stories Quarterly contained the monthly issues for May, June and July 1942. They retained their individual page numbering, but were rebound as a single volume. As a consequence your 50¢ bought 828 pages, a massive 16.5 pages per cent.

Somehow this ought to qualify as the biggest single pulp issue, but the purist in me disagrees. It was, after all, just a rebinding of three pre-existing issues and though it sold at a bargain rate, it was really second-hand. So, let’s discount it.

But let’s just go back to those bumper Amazings. Firstly, Amazing used a bigger type font than usual on the stories so that the wordage per page was lower than the general pulps, around 600. Much smaller type was used for the letter columns and fillers, but these are secondary to the fiction, or ought to be. Because they carried a lot of artwork and adverts these issues averaged some 125,000 words, or 5,000 words per cent.

And secondly…well, were the 1942 Amazing’s the biggest pulps ever?

Perhaps they were in the United States—unless someone can tell me of any others. But let’s not forget the British pulps.

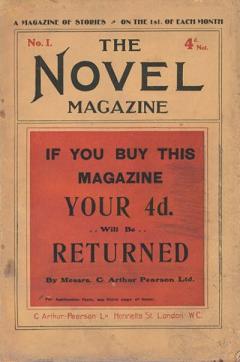

The rise of the all-fiction pulp had started with The Novel Magazine in April 1905 (cover at right), though this was a standard 144-page magazine selling for fourpence. In those days, of course, there were 240 pence to the pound, so fourpence was 1/60th of a pound. Back then the pound sterling was equal to $5, more or less, so fourpence was 1/60th of $5 or 8.33 cents. So in Britain The Novel gave you 17¼ pages per cent. What’s more The Novel used fairly small type, so that an average issue ran to about 90,000 words, meaning one cent bought just under 11,000 words.

The rise of the all-fiction pulp had started with The Novel Magazine in April 1905 (cover at right), though this was a standard 144-page magazine selling for fourpence. In those days, of course, there were 240 pence to the pound, so fourpence was 1/60th of a pound. Back then the pound sterling was equal to $5, more or less, so fourpence was 1/60th of $5 or 8.33 cents. So in Britain The Novel gave you 17¼ pages per cent. What’s more The Novel used fairly small type, so that an average issue ran to about 90,000 words, meaning one cent bought just under 11,000 words.

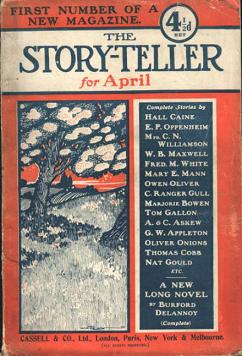

It wasn’t The Novel, though, that created the popularity for the all-fiction pulp in Britain, it was The Story-teller. That began in April 1907 and ran to 176 pages for 4½ pence, or just under 10 cents. The Story-teller had slightly large type but ran to around 110,000 words per issue, so one cent bought 17.6 pages and 11,000 words.

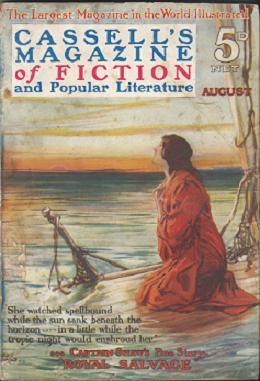

The Story-teller (April 1907 cover at left) was published by Cassell, and the success of the magazine caused Cassell to revamp its fiction magazines. They launched The New Magazine in April 1909, though this was only 144 pages at the outset, inclusive of a theatre photo supplement. But of much greater significance was Cassell’s Magazine. This was completely revamped and relaunched in April 1912 as an all-fiction pulp magazine. Its first issue boasted 288 pages selling for five pence, or just over 10 cents. So one cent bought you almost 29 pages. What’s more, the typefont for most of the contents was smaller, allowing up to 800 words a page, so I reckon a whole issue ran to about 225,000 words, or 22,500 words per cent. This was far in excess of anything in the US and Cassell’s rightly boasted on its front cover “The Largest Magazine in the World.”

The Story-teller (April 1907 cover at left) was published by Cassell, and the success of the magazine caused Cassell to revamp its fiction magazines. They launched The New Magazine in April 1909, though this was only 144 pages at the outset, inclusive of a theatre photo supplement. But of much greater significance was Cassell’s Magazine. This was completely revamped and relaunched in April 1912 as an all-fiction pulp magazine. Its first issue boasted 288 pages selling for five pence, or just over 10 cents. So one cent bought you almost 29 pages. What’s more, the typefont for most of the contents was smaller, allowing up to 800 words a page, so I reckon a whole issue ran to about 225,000 words, or 22,500 words per cent. This was far in excess of anything in the US and Cassell’s rightly boasted on its front cover “The Largest Magazine in the World.”

Alas, it only ran to that size for one issue but dropped to 256 pages until the end of 1914 when wartime restrictions started to bite. By 1918 it had dwindled to 128 pages. But even at 256 pages it gave over 20,000 words a cent.

Cassell’s had one last fling. In 1915, with paper saved from the monthly Cassell’s they issued a bumper Cassell’s Winter Annual. This ran to an astonishing 320 pages though it sold for an alarming two shillings. The exchange rate had slipped a little by then, but to all intents two shillings was equal to 50 cents, meaning the magazine equalled 6.4 pages per cent. Although I’ve seen the issue I don’t own one so have never counted the wordage. My very rough estimate is that it was about 180,000 words, or only about 3,600 words per cent. What’s more the contents were almost entirely reprint, from earlier Cassell titles. Even so, it wasn’t a rebinding, like the Amazing Stories Quarterlys, and it was a single magazine issue. It thus stands as the biggest single pulp magazine ever published, so far as I know. However, my laureate goes to Cassell’s Magazine not only for its size but how much it packed into each issue.

The following chart lists the key titles in rising sequence of size. Is there a bigger example?

Magazine/Relevant dates | Total pages | Cover price | Pages per cent | Wordage per cent |

The Argosy, Oct 1896-Oct 1918 | 192 | 10¢ | 19.2 | 13,500 |

Popular Magazine, Dec 1906-Mar 1917 | 224 | 15¢ | 14.9 | 9,800 |

Blue Book, Oct 1914-Feb or Mar 1917 | 240 | 15¢ | 16.0 | 9,600 |

Amazing Stories, April-July 1942 | 276 | 25¢ | 11.0 | 5,000 |

Cassell’s Magazine, April 1912 | 288 | 5d (10¢) | 29.0 | 22,500 |

Cassell’s Winter Annual, 1915 | 320 | 2/- (50¢) | 6.4 | 3,600 |

(Cassells’s Magazine, August 1913, with the banner across the top reading “The Largest Magazine in the World Illustrated.”)

© 2009 Mike Ashley

First published in Another Part of the Forest #21 produced for PEAPS Mailing 87, May 2009