Reviewed by Ryan Holmes

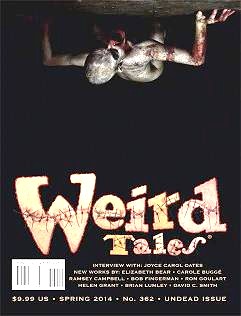

Weird Tales #362 contains sixteen original works of horror divided into two sections: undead and unthemed fiction. Powerful flashes of horrific epiphany and abysmal dives into the psyche of the disturbed lurk within like the lingering chills of a dark and drafty, old house. What’s more, Weird Tales provides dedicated artwork throughout the stories that really pushes the collection to the next level.

“#rising” by Cynthia Ward is set in Twenty Nine Palms, California and follows two half-sisters as they flee a zombie apocalypse. As a whole, this story creates a spin on the zombie trope that is both unique and weird. Just when we think we have Ward’s mind figured out, when we’re (if you’re like me) growing tired of her assault on faith, she turns the tables on us and creates the only plausible zombie scenario. She transforms the ugly hopelessness of atheism, the perceived intolerance of religion, and the horror of death into something beautiful, accepting, and peaceful. Ward’s voice feels genuine and natural overall, but the narration, and especially the dialogue, contains chunks of stiff prose stemming from uneven contraction usage, extraneous word usage, and over explanation. It distracts at times, but it isn’t worth missing the amazing reveal at the end.

Bob Fingerman’s “Ink” takes place in an urban art studio after a zombie outbreak, but not the run of the mill zombies. These have antlers with bulbous pods full of spores growing off them like fruit. Chuck, a graphic novel artist with a passion for all things zombie, decided to shelter in place. He’s alone, after his five studio mates abandoned him one by one, and is running out of supplies, pondering what to do, when someone, something, enters the studio. Fingerman’s story reimagines the tired tropes of zombie lore through the eyes of a self-proclaimed expert turned hypocrite. With clever prose and a brutally honest voice, the story takes a deep dive into the thoughts and motivations of someone who realizes he was never the ‘real deal’ but is determined to make the best of a terrible situation.

“Happy Hunting Ground” by Andrew J. Wilson is set in the old west, beginning in a place called Misery at the end of the line somewhere just east of the Rockies. It’s narrated in a first person-third person-first person style of a stranger listening to the recounted adventure of the Kid, now well past his early seventies, while the stranger feeds him whiskey at a bar. The Kid, a victim of his own circumstances, is indirectly dragged into a Marshal’s posse by the bounty hunter who saved his skin. The posse pursues a war party of Ute Indians and finds themselves in the Happy Hunting Ground. Temporal instability and a tendency for things to die hard raise the difficulty of navigating this landscape of long-toothed cougars and ‘hairy-phants.’ The story’s plot has potential but minor scene inconsistencies like getting swallowed head first only to be dragged into the woods later leaving behind a convenient blood trail, decoupled chronological order of events like telling us the saber cat jumped out of the woods only to then describe the details leading up to its appearance, and a growing tendency to over explain as the story unfolds leaves the experiencing feeling unpolished. Add to this Wilson’s choice to start the story with a stranger listening to an old man’s tale and then to have that old man omit what would have been a decent climax, and we are left aggravated by an unresolved story arc with an unnecessarily long middle. Better to tell the story from Kid’s perspective as it unfolded and give us the climactic ending we craved instead of the ‘that’s another story’ which with we were left.

Justin Gustainis delivers “Until I Come Again,” a reimagining of the fate of the infamous Jack the Ripper. Jack meets a stranger on the street after concluding his ghastly business with Mary Jane Kelly. Jack ponders the stranger’s identity but casually walks by, confident the police and everyone else are clueless. His overconfidence is his undoing. Jack, like the women he victimized, becomes a slave to his world, unable to change his fate, his circumstances. Unfettered freedom replaced with mindless loyalty. Is his fate better or worse than the impoverished women he preyed upon? They, at least, have free will, but with it comes understanding of their misery. Jack winds up with neither. This story gives us insight into the plausible mind of a twisted killer: his motives and his contempt for the world. Then it thrusts him into the clutches of an unlikely savior and proposes a disturbing parallelism with the Son of Man. The difference between them is free will. The story is written well, and Gustainis injects all the necessary historical details, but its open ending is more like a prologue to a novel and less like a proper denouement.

“The Waves from Afar” by Kurt Fawver turns the luminously beautiful surf of the Gulf of Mexico, with its sudden and unexplainable coloration phenomenon, into a disturbing and deadly pandemic, made all the more terrifying by its enticing, near hypnotic aesthetic. A vacationing family of four, along with a host of others, journeys to Clearwater, Florida to witness the luminescent phenomenon and fall victim to the unseen threat when it manifests. The story centers on the father, and his struggle with the horrific events. It is a fresh, certainly weird, concept that infuses us with a sense of fear and wonder. Fawver uses a practically all-narration style that distances the reader from the action despite the long and deep internal repast we get from the father as the POV character. Perhaps adding to this distance, he is painfully short on emotional expression, as if detached, and does not respond with the level of desperation we might expect were we faced with similar circumstances. This detachment makes it difficult to relate to him. Couple this to no definite resolution of the phenomenon and an ending rife with anguish, and we walk away with a truly unnerving experience that doesn’t soon wane.

Keris McDonald’s “Darkling I Listen” begins with a woman recounting a story to an immature ghoul as the sunlight in an abandoned land fades to twilight. She tells the story of a small girl traveling by wagon with her fortune-telling father who reads the stars to pay the bills. They enter a new kingdom, and her father announces their services in an open market. We get the sense right away that something terrible is going to happen to them. McDonald pairs this sense of danger with the woman telling the story. As the sun fades and the ghoul becomes more comfortable, we wonder about the fate of the woman. Then the sense of danger shifts when her story introduces a powerful wizard. We get the notion that it’s the ghoul who is wary. The story is visually imaginative, layered with misdirection and rising tension, and subtle with its plot twists—a sophisticated style. In the end, the tension resolves into a satisfying feeling that, despite the woman’s plight, all is right in her world.

“Therapeutic” by Tim McDaniel introduces us to a world of irrational fears and a patient who’s tried everything to overcome them. The story begins with Jeffrey Harlacker (fear of spiders) flipping through a Nat Geo mag (after checking for articles about spiders) in the waiting room of a clinic for Systematic Desensitization. While there, he encounters another patient, Val, who insists on keeping the blinds closed. We learn from their conversation that Val has a number of irrational fears, though Jeffrey doesn’t notice what those fears have in common, and that he hopes this new therapy will succeed for his people where all others have not. Jeffrey assures him it will, and indeed it does. This story points out how irrational and insignificant many fears can be in the grand scheme of things. It also hints at the folly that can befall us all should we shake off all our fears, all our inhibitions, and attain true freedom to do as we please.

Ron Goulart’s “The Bride of the Vampire” is set in 1900 London where Harry Challenge, an American detective with his father’s Challenge International Detective Agency, has arrived to solve a case involving a missing artist’s model and claims that she has fallen victim to the Undead Brotherhood of vampires. Action and mystery abound as Harry tracks down leads and chases suspects. Harry is a no nonsense type of detective that is easy to find likeable. He seems over his head at times but proves to be well prepared. With an equally likeable sidekick illusionist, the Great Lorenzo, the story concludes with a satisfying and humorous ending.

“One Day at a Time” by Charles Black is a western set in Dodge where an unidentified entity is vengefully hunting down the Day brothers. The tension builds with each Day encounter. A great deal of character develops in short order, and the end is sudden but powerful. It causes us to reappraise the entire story and wonder how Black pulled it off in so few words.

James Aquilone’s “From the Casebook of Dead Jack, Zombie P.I.: “The Amorous Ogre”” picks up with Jack taking a case from a nauseatingly cute pixie who wants her wayward daughter rescued from the courtship of an ogre. This story is so entertaining we must read it a second time: first because it’s so damn enjoyable, and second in order to concentrate on the themes it employs in order to provide an adequate review, and they are numerous. Aquilone deals with addiction, naivety, prejudice, love, and free will, to name a few. Smarter people than I will surely see more subtle themes. This was easily my favorite story out of the sixteen packed into WT #362. Aquilone delivers a fantastic hook in the beginning, carries the reader through the middle with a symphony of emotional beats: intrigue, humorous cynicism, tension, failure, perseverance, more humorous cynicism, irony, and ends the story with a proper denouement, one that is satisfying, funny, and hooks the reader like a narcotic. What fault can I find with it? Let me scratch my head on that one a minute. The only thing I got is there wasn’t enough of it. There’s this one scene especially, with Aquilone’s awesomely created sidekick that occurs off stage. I was so disappointed; I almost latched my hitch to the little guy, if only that were possible. I was really looking forward to reading the monumental task Aquilone builds up, so yes, amazingly my only problem with this story is that he didn’t include more of it. I’m like a junky getting the shakes just reviewing it. I need another hit and ‘a shot of Devil Boy’ to chase it with.

“Letting Go” by Jamie Lackey creates a harsh environment around a graveyard and a morbid mood of reflection on what should otherwise be a joyous day of celebration, a birthday. Lackey couples a woman’s twenty-fifth birthday to the twenty-fifth anniversary of her mother’s death and does so with brilliant insight. We are easily lulled into sympathizing with the woman and her loss as if she is a close, even intimate friend. Add to this the engagement ring on her finger and the subtle implication that it just got there, and we’re overwhelmed by a powerful urge to pull this woman into our arms and let her cry it out. Then comes the mystery behind the locket she stole ‘from her father’s desk when she was six,’ the one that froze to her chest, that she never had a chance to open. We’re empathetic already. Now we’re intrigued, as is the woman wearing the locket. Her curiosity, her unwillingness to let go might cost her everything. Equally potent is the story’s denouement. Lackey delivers it in a single sentence. This one affected me on a personal level, and I recommend anyone who knows someone who has lost a loved one to read it. Anyone who has lost a loved one may find it emotionally overwhelming.

David C. Smith’s “Coven House,” dedicated to Ken W. Faig, Jr., is an impressive and original reimagining of the haunted house tropes. The mystery behind the house begins right away, as does the sense that something lies hidden between the three characters: Curt Peterson, a psychic investigator; his wife Jill, suspected to be paranormally sensitive; and Eric Tomko, the smart aleck, freelance writer and paranormal skeptic. Smith builds, or rather unwraps, layers of complexity with both the house and its guests. Conflict crowds the story like a small apartment hosting family for the holidays. It’s hard to imagine room for any more, and Smith delivers it like quicksand. The more our eyes grasp at the words on the page the more it sucks us in. But this is a haunted house story, so how scary is it? In a word: haunting. “Coven House” succeeds in causing us to jump when a family member bumps something in the room. We’re surprised to find them there. We feel that nostalgic prickling of the skin from our younger years. Our breath catches, and we delight in succumbing to such irrational fears again while talking down the little voice telling us to check the lock on the doors. This one will linger with us, revisit us when we’re alone in a dark building, caution us the next time someone wants to play with a board that plays back or array lit candles in a circle and start evoking the four points on a compass. It makes us wonder if there’s any truth to the lore and convinces us not to put it to the test. The story is a warning, but will we listen?

“Thinking of You” by Nicholas Knight is a clever and concise story about temptation, vulnerability, and predation. A wealthy man waiting for the subway train because his car is in the shop spies an attractive woman, but how to approach her? Knight puts us in the head of a man just as unsure about himself as the rest of us. He’s still the predator. Women don’t chase him unless they know he has money, right? Knight reveals to us how subtle a woman’s power can be and how easily men fall prey to it.

The late M. R. James left behind two incomplete drafts: “Merfield House” and “The Game of Bear.” Helen Grant completed “The Game of Bear” and published it here with permission from N. J. R. James and Rosemary Pardoe. “The Game of Bear” is set in a nineteenth century country town near Cambridge and involves the telling of a local legend: the death of Henry Purdue. Henry’s friend, Mr. A, who witnessed the events during his visit with Henry during Easter vacation from the university, conveys the details of the legend to Mr. B, another college colleague. The game of Bear, a children’s game akin to Hide and Seek where those hiding jump out to scare the seeker, serves as a metaphor for what haunts Henry Purdue and incites Mr. A to tell Mr. B the story after Mr. A commands his nieces and nephews to stop playing the game in the rooms outside his library. M. R. James, who lived between 1862 and 1936 and served as provost of King’s College, Cambridge from 1905 to 1918, uses a classical style of prose. The characters and events are consequently distanced from the reader. Helen Grant performs a seamless job picking up where James left off. There is enough to the draft to establish the main conflict, and Grant steers the story true. We can imagine M. R. James himself might have ended the story in much the same way. It takes a special skill to emulate another author’s style and vision, and Grant succeeds quite admirably.

“Formidable Terrain” by Elizabeth Bear introduces a biologist investigating a carcass so large its decaying mass crushed Detroit Metropolitan Airport. Bear imagines the blinding stench and writhing critters that so much dead flesh would create and assaults our senses with vivid, pungent prose. Told in second person, you calculate the enormity of such an event while circling over it in a helicopter, and before the story ends, you’re struck by the cause and what it means for the future. Bear strips away our presumptions on the size limitations of life, and does it with an economy of words that only makes her prose more powerful.

Ramsey Campbell’s “The Impression” is contemporary horror about a boy named Alan and his struggle with internal demons. Abandoned by his father, overworked and unappreciated by his mother, Alan’s only companionship comes from his grandmother who passes on to him the art of rubbing. Together, they find an abandoned sarcophagus and create a rubbing of the facial likeness carved into its cover stone. Campbell uses the rubbing as catalysis for the boy’s mental struggles. This story delves deeply into psychological and sociological themes with such a subtle progression, we, like everyone in Alan’s life, don’t realize how disturbed he is until it’s too late. Even when the light is cast on his psychotic break, we hardly acknowledge its severity. It all seems so perfectly natural.

Ryan Holmes is a Marine Corps grunt turned aerospace engineer who works at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center and writes science fiction and fantasy in life’s scant margins. You can find his blog at: www.griffinsquill.blogspot.com

Weird Tales #362, Spring 2014

Weird Tales #362, Spring 2014