“Mary Smith” by Paul E. Martens

“Mary Smith” by Paul E. Martens

“Faraji” by Will Ludwigsen

“The Man Who Carved Skulls” by Richard Parks

“Six Scents” by Lisa Mantchev

“Working out our Salvation” by Trent Hergenrader

“Directions to Mourning’s Deep” by Scott William Carter

“Wake 2041” by Douglas Kolacki

“The Release” by Kurt Newton

“Spider Comes Home” by Gerard Houarner

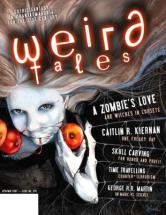

Weird Tales bills itself as “gothic fantasy and phantasmagoria for the 21st century.” That’s pretty catchy, but I couldn’t tell you what it means. What I can tell you is that Weird Tales is a diverse collection of fiction, commentary, artwork, reviews, letters, and an interview that spans eighty pages at the ridiculous bargain price of $6 US ($8 in Canada). If it has a weakness, it’s that the stories, at least in this issue, offer no particular theme or represent any single genre, though I suppose they all do fall under the category of weird. There’s a little horror, a little comedy, some romance, a dash of drama, and a smidge of science fiction. It is therefore unlikely to excite purists of any stripe. It presents widely varied stories and will appeal most to someone who simply flops into a recliner, opens the magazine at random, and expects simply that it provide entertainment without preconditions. Come to think of it, “entertainment without preconditions” might be a better slogan than “gothic fantasy and phantasmagoria for the 21st century.”

In Paul E. Martens’s “Mary Smith,” Frank O’Casey has someone living with him. Most people think she’s his grandmother, or perhaps even his great grandmother. Frank has no idea who she is or where she came from. All he knows is that she won’t leave, she’s ruining his life, and she’s maybe very, very old. Perhaps, Frank discusses with his friends, it’s time to do something drastic. This is an excellent first story for this issue, a simple and straightforward ghoulie story to whet the appetite.

“Faraji” by Will Ludwigsen is a difficult story to categorize. It has elements of science fiction but is almost philosophical in its discussion of free will versus predestination. A man rotting in a jungle prison in South Africa is about to kill himself in his cell, convinced help will never arrive, when a teenage boy is thrown into the cell with him. The boy claims to see all times at once—he knows his past, and he knows his future—and he knows his fellow prisoner will do great things if he only chooses to escape. While interesting, it lacks a certain visceral power, perhaps because we don’t particularly care about either the guy in the cell or the boy. Also, the boy’s contented acceptance of mistakes he makes in his own future, despite the fact that he clearly sees them coming and does have some leeway in formulating his own destiny, is both disagreeable and disheartening.

In an ancient jungle society, the human skull is highly revered. Upon death, a bass relief is carved into the skull depicting the achievements of life, and the skull is stored in a place of great sanctity. The man who has the skill to carve these skulls is highly revered and envied. So goes the story of “The Man Who Carved Skulls” by Richard Parks. One of the greatest skull carvers ever is reaching the end of his days, and his wife, a grand and proud woman, is worried that he won’t be able to carve her skull when she dies. Whatever can she do? Though this story is more a drama than anything else and so fits quite poorly with all the other stories in the issue, I really like this premise and the way the author plays it out. It is also written in a genuine style using an almost earthy structure that nicely compliments the story.

I often marvel at the economy of words that allows an author to tell a complete and fulfilling story in the span of just a few pages. More beautiful then is “Six Scents” by Lisa Mantchev, which gives us six. Each storylet contains a central kernel of simple narrative based upon a single strong scent. Slithering in with undulating black gloss reptile sheen, each builds an exotic minimalist altar, makes its sacrifice, and moves on.

I wish that “Working out our Salvation” by Trent Hergenrader had been the final story in this issue (though “Spider Comes Home” is a very good closer). As a nicely polished ghost story it would have made an excellent bookend with “Mary Smith” to contain the entire issue neatly, though it is an excellent story regardless of where it resides. It has the classic, timeless structure of just about every ghost story you’ve ever heard, though it is entirely unfamiliar to me. A boy’s father is killed in a mining accident. That boy sure does miss his father…

Perhaps I’ve never been to that point, but the entire premise of “Directions to Mourning’s Deep” by Scott William Carter struck no chord with me—that there are some tragedies so acute, sadness so devouring, that you cannot get past them and so seek out this storied tavern, “Mourning’s Deep.” In this dark and pensive place, a stranger waits to literally hear you pour your heart out, and then your sadness will be gone. While it strives for a traditional wives’ tale ghost story atmosphere, for me, at least, it fell short. Perhaps if my dog had died more recently.

A lonely old woman enters a church for shelter from the rain and finds herself at a wake. Each speaker for the dead tells of the deceased loneliness, his solitude, his friendlessness throughout his life. If true, who are all the people at the service? I appreciate that “Wake 2041” by Douglas Kolacki offers neither half-hearted nor half-baked explanations for the wake we are witnessing. If the reader simply accepts what is happening, we receive for our troubles a fine if depressing story of the irredeemable tragedy of living and dying alone. If only there was some way to go back and do it all differently.

Trapped in a loveless marriage? Forced to raise your many children without help from your inflexible and high-maintenance wife? Sure, she promises to bite your head off and devour your corpse like she should, but she never seems to follow through. OK, so maybe these are not the issues faced by most of us, but our sympathies are effectively evoked from an insect’s (I think a praying mantis’s) point of view in “The Release” by Kurt Newton. Written clearly with a lighthearted, almost comedic touch, we can nonetheless commiserate with his Sisyphusian duty. Will it be the final straw when she brings another lover into the hive?

Saturated with musical and rhythmic undertones, “Spider Comes Home” by Gerard Houarner reads much like a tribal myth. A young boy leaves his village to find and confront a man creature known as Spider, upon whom all the villagers blame their misfortunes. How much better would everyone’s life be, the boy thinks, if only he can convince Spider to stop doing the bad things he does? Rich in imagery and almost epic in nature, it is a deeply satisfying conclusion to this Weird Tales issue.