"Tiny Voices" by James Van Pelt

"When You Can’t Go Back" by Nina Kiriki Hoffman

"Diplomatic Relations" by Don D’Ammassa

"Scare Tactics" by Jennifer Rachel Baumer

"Bliss" by James Michael White

"The Dandelion Clock" by Stephen Couch

"The Feather" by Donald Lucio Hurd

"Untainted" by Katherine Woodbury

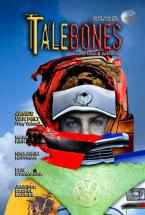

Talebones is back with their 2006 summer issue. Before I start the review, I would like to mention that if you enjoy Talebones and you haven’t subscribed, think about it. Talebones came perilously close to issue #33 being their last.

The first of the eight stories in this issue is James Van Pelt’s “Tiny Voices.” Corey is a nurse caring for the elderly Stella, and they are surrounded by a world of sentient objects, with everything implanted by sentience chips. Corey faces the twin challenges of Stella’s death and her own unexpected pregnancy—an aberration in a world where no one has a baby unexpectedly, and women don’t seem to carry children to term. In addition to Corey’s struggles, Stella is exploring the meaning of consciousness. She perceives her world through the “senses” of objects—refrigerator, coffee maker, desk, and television—and begins to wonder what the death of her body will mean.

Van Pelt creates a world where life is taken for granted and death is almost overlooked. Everything seems alive; objects talk to everyone about the things they perceive as important. Cars talk about traffic, refrigerators about food, and pencils about words. Here, Corey seems like a bit of an anachronism. She’s concerned about Stella, upset by the prospect of her impending death, and is shocked by her own pregnancy. Corey’s internal struggles are mirrored by, of all things, writing utensils. Her pencil is afraid of being used up, of dying, while she has a pen who only wants to be useful despite a factory defect that makes it skip.

I liked “Tiny Voices.” Stella’s exploration highlighted Corey’s internal struggles while the concerns of the inanimate heightened the concerns of the living. I did occasionally find the point of view distracting when Stella and Corey were together, but overall, “Tiny Voices” is an excellent story and well worth reading.

In “When You Can’t Go Back” by Nina Kiriki Hoffman, Alice and Mandy used to be things. More specifically, Alice was a refrigerator and Mandy was a recliner. They have discovered that they aren’t the only ones, and are now attending a convention for People Who Were Formerly Other Things. Attending this convention highlights Alice’s discontent, while Mandy is relatively happy-go-lucky. Alice misses having her own purpose; she misses her illusions.

“When You Can’t Go Back” explores the very human preoccupation of wondering what your place is in the world. Alice has been forced from her comfort zone and has lost her sense of purpose. It’s a topic rife with possibilities in a world where there is a new bestseller every week about this same issue.

“When You Can’t Go Back” has excellent characterization, but doesn’t go as far as I had hoped it would. Alice realizes the level of her discontent, but she wallows in it rather than thinking about how to resolve it. Still, it was an interesting concept, and Alice is a compelling character.

“Diplomatic Relations” by Don D’Ammassa is a humorous story about the unintended consequences of miscommunication. Travis owns an interstellar ship and hauls cargo, and occasionally passengers, through the cosmos. He occasionally hooks up the slightly less honest Devlin to do odd jobs. This time, Devlin has a line on an alien race’s ambassador in distress who has a disabled ship. All they have to do is offer the ambassador a ride home and they’ll be rewarded with gifts of immeasurable value. Of course, there are always complications.

D’Ammassa’s story is straightforward and very classic science fiction with semantic nuances being the root of Travis and Devlin’s troubles. The story is fun, despite relying on the final joke for its kick. Readers will enjoy this light romp.

Jennifer Rachel Baumer’s “Scare Tactics” is an eerie Halloween story. Jack is a drifter, a loner who takes a handyman job for Thira, an artist in the Pacific Northwest. Jack works for Thira for longer than he intended, and he feels aged and worn by his contact with her. Yet, Jack also has flashes of something else hanging around the edges of his mind. There is an air to Thira’s estate, a creepiness enhanced by the stories of the regulars at the local bar. But in the end, you aren’t sure who is more unsettling, Thira or Jack.

“Scare Tactics” is creepy. Baumer effectively handles her ambiguous protagonist, Jack, and creates a keen dissonance from strong tension in an otherwise quiet tale. You’ll wonder what’s in the basement of that creepy old house every town has, exactly the effect a good Halloween story should have.

“Bliss” by James Michael White is an even creepier story. Bliss is literally trapped in her own skin. Dr. Mandrake is the psychiatrist who tried to treat her when she flayed her skin from her body. And then when she flayed a man and then herself. He gave up trying to treat her when she flayed his wife; then he just wanted revenge.

"Bliss" made me speculate about the mental processes of people who cut themselves. Is it so far fetched that they might be trying to feel something beyond their skins? Bliss certainly is, and once she realizes that, she tries to convince everyone else. The sparks fly when she tries to convince Dr. Mandrake, but that’s as much his fault as hers.

White pairs disturbing idea with excellent characterization to make a dark and creepy story filled with extremes—wanton extremes that make you shudder. Even though White’s description aren’t particularly graphic, they are enough to evoke a mental image, one far more disturbing than something more explicit. Sensitive readers might find it a little more than they can handle, but for those who can take it, “Bliss” is a compelling ride.

“The Dandelion Clock” is Stephen Couch’s first story in Talebones. Michael is trying to raise a family during the Dust Bowl in Oklahoma. The world has already gone awry with the drought and the wind whipping all the land away into the air. He’s broke and too stubborn proud to take the grudgingly offered help of his father, and now he has to face something new. His family is getting sick, infected with a kind of spore that takes them from him, turning them into something like a seeding dandelion, offering them up to the wind.

“The Dandelion Clock” captures what Dust Bowl families faced, especially the fears of the father trying to provide for his family in a broken land. Michael is devoted to his wife and children, trying to provide something from nothing. The dandelions that his children and wife become are a metaphor for his dreams of a better, cleaner life blowing away, just like the land he came to farm. Everything blows away until all he has left are his high ideals, and they don’t offer him much comfort.

“The Dandelion Clock” succeeds both as a metaphor for a painful past and as a story. And like a good metaphorical story should, it stands also as a metaphor for the present, a world that is on the verge of destroying itself in the way the Okies destroyed Oklahoma. It’s a great story and a vivid picture of a the impact people have had and could have.

In Donald Lucio Hurd’s “The Feather,” the birds have all died and no one is sure why. Stanley Pidgeon finds a feather falling from the sky which gives him and his wife, Carol, a symbol for hope.

Birds are the embodiment of hope in this tale of hope and hope dashed in a subtly bleak future. They represent recovery from the past and are a symbol of inspiration. But Carol and Stanley realize they can’t escape the past. Both cautionary and saddening, Hurd’s story speaks not only of what we are doing to the world, but also of what so many of us do to ourselves. He offers his characters a false symbol, and they suffer for it.

“The Feather” might be the best story in this issue of Talebones. Its simplicity is deceiving. There is a lot to think about, reinforced by excerpts of poetry, in the rise and fall of characters’ emotions as they wait. It’s a story well worth reading, but it might leave you a little pensive.

The final story is Katherine Woodbury’s “Untainted.” Kemp is a retired spy-turned-teacher, instructing employees of Guarantee on the espionage games they might have to play. Phaedra, a student, hates the class and what he teaches, but she doesn’t quit. His latest assignment is one of seduction. Students may pick their target, but they have to obtain something, a symbol of their conquest. Phaedra picks Kemp. But the conflict isn’t really between Kemp and Phaedra; it’s within Kemp. He recognizes in Phaedra what he feels, the past he hates. Phaedra is Kemp’s analog, what he wishes he could have been soon enough to stop him from being a tool for Guarantee.

“Untainted” carries itself with quick dialogue and a deep understanding of its characters. Woodbury does an excellent job showing the self-loathing in both Kemp and Phaedra. She does as well with showing their respective motivations for the actions they take in response to their inner turmoil.