“The Geezer Squad” by Annie Reed (non-genre, not reviewed)

Reviewed by Victoria Silverwolf

Two-thirds of the stories in this issue are original. Of these, the majority are science fiction or fantasy. The others are comedy and crime fiction.

The title animal in “The Dog That Ate Homework” by J. Steven York doesn’t just devour classroom assignments, but instruction manuals and the pages of an encyclopedia as well. The really weird thing is that it absorbs all the written knowledge it dines upon. This allows it to rewrite an eaten term paper for its young master, and perform magic tricks from the directions it swallowed. This whimsical fantasy has little plot, but is a pleasant read.

The narrator of “Battery-Operated Boyfriend” by Barbara G. Tarn is a sex robot. A pair of identical twins, one of whom has changed sex, steal it in order to test its capabilities and enhance its abilities. Despite this seemingly salacious premise, there is nothing explicit in the plot. The story ends in an anticlimactic way. Although the theme of robotic sentience is discussed, this is done in a superficial fashion.

“Offensive in Every Possible Way” by Robert Jeschonek takes place in the near future. Language has evolved—or devolved—in such a way that heavy use of profanity is an expected part of all normal writing and conversation. The story takes the form of the diary of a girl trying to tutor a boy who has a neurological inability to use such words. Due to the nature of the plot, the diary is full of blacked-out spaces where profanity should appear. This makes the story a chore to read. Despite this flaw, the characters are likable and the author has a point to make about the use and abuse of language.

The comic misadventures of a missionary/con artist appear in “The Sport of Queens: A Lucifer Jones Story” by Mike Resnick. Since 1985, this prolific writer has spun dozens of tall tales about the title character, as he wanders the globe encountering the bizarre. The stories, in general, are lighthearted spoofs of pulp fiction.

In this story, Jones is lost in the Australian Outback during World War Two. He wanders into a town where all the males, except for children and the elderly, are off at war, leaving man-hungry women behind. The desperate ladies stage a knockdown, drag-out fight, with Jones serving as both referee and prize. Our antihero has to figure out a way to escape the prospect of marriage.

Although there are no overtly supernatural elements, the outrageous plot and wild exaggerations qualify the story as borderline fantasy. Nearly every line contains a joke. The humor gets very silly at times, and the ending is weak, but readers looking for slapstick will appreciate the author’s tomfoolery.

The setting for “Maiden’s Dance” by Rebecca Lyons is a fantasy world inhabited by humans and creatures of Faery. The protagonist is the mother of a young woman. During a carnival, her daughter attracts the attention of one of the ageless beings of the magical realm. This leads to a revelation about the mother’s past. The author creates a genuine sense of tragedy in a story without villains or violence. The characters, human and otherwise, are fully realized persons, with a realistic mixture of flaws and virtues.

“The True Story of Stanley and Stella” by Johanna Rothman lightens the mood with a romance between a fish and a duck. What seems at first to be pure whimsy turns out to have aspects of science fiction as well. This is a story best described as cute, with both the positive and negative connotations of the term.

“Death Be Nimble” by James Gotaas is a very short tale about a dead murderer who returns to the world of the living through black magic. It packs a great deal of gruesome detail into a small space. The twist ending is not unexpected, but otherwise this is an effective horror story.

Victoria Silverwolf notes that this magazine also contains a computer-drawn comic strip, old illustrations with funny captions, and a lot of ads.

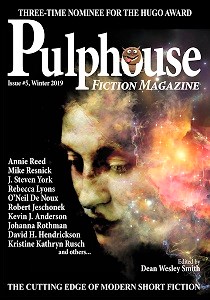

Pulphouse

Pulphouse