“Dead Men Do Tell Tales” by Teel James Glenn

“The Dusk Next Door” by Mark Pellegrini

“Fossils of Truth and Grace” by E. E. King

“The Gold Exigency” by Michael Tierney (serial, not reviewed)

“Children of Summer” by Louise Sorensen

“Metamorphoses at the Gate” by Lysander Arden

“The Chilling Account of the Wolf-Bann of Krallenburg” by J. E. Tabor

“The Angel Hanna” by Rodica Bretin

“Trapped in the Loop” by Jim Breyfogle

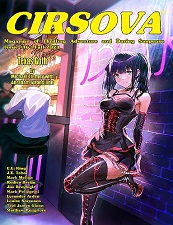

“Texas Goth” by Michael Tierney and Abraham Strongjohn

“Black Sky, White Knight” by Mark Mellon

“To a Dead Soul in Morbid Love” by Matthew Pungitore

Reviewed by Victoria Silverwolf

The eleven works of short fiction in this issue lean heavily to horror and dark fantasy, in settings ranging from the modern world to the remote past to places that never existed.

“Dead Men Do Tell Tales” by Teel James Glenn takes place in a version of New York City inhabited by all manner of supernatural beings. A zombie asks the narrator, a sort of private detective, for help. The hero arrives at the scene, to find the zombie’s head removed from its body, but still living. He gets involved with a crime lord and his vampire assistants, who are seeking an object of enormous magical power.

Like much urban fantasy, this story reads like hardboiled crime fiction. Some elements, such as flying carpets, seem overly whimsical for its dark, violent mood. There is a touch of sardonic comedy, particularly in the form of the decapitated zombie. The work has so many different fantasy elements that it becomes overwhelming, its multiple supernatural concepts not always blending into a coherent whole.

In “The Dusk Next Door” by Mark Pellegrini, once a year a high school student is selected to carry children’s drawings to the mysterious inhabitants of a strange town. One such teenager enters the weird place, encountering frightening creatures. His journey leads to a bizarre change in the situation.

My vague synopsis fails to convey the pure surrealism of this horror story. Like a nightmare, it is full of disturbing, irrational images. Much is left unexplained, which I assume is a deliberate choice on the part of the author. Readers who prefer an eerie mood over clarity will best appreciate it.

The protagonist of “Fossils of Truth and Grace” by E. E. King is a young scientist who has attempted suicide, a fate which took the lives of many of her female ancestors. She is treated for mental illness and seeks rest at an old manor home in Cornwall. It turns out her mother and her grandmother both stayed there. Investigating the surrounding area, she discovers her family’s link to a woman burned as a witch hundreds of years ago.

Although the bare bones of the plot involve the familiar theme of a curse placed on a family by someone executed for witchcraft, the story appears to be more concerned with the main character’s psychology. Much of the text describes her thoughts and feelings as she explores the manor home and the countryside, as well as delving into her past. The piece is fairly long and quite leisurely, requiring patience on the part of readers.

“Children of Summer” by Louise Sorensen takes place in a postapocalyptic future world in which animals and even plants have mutated into giant, deadly creatures. Two people set out from their compound, heavily armed and armored, in search of another hunting party that never returned.

With grasshoppers the size of horses and corn with razor-sharp leaves, the story may require more suspension of disbelief than one can easily offer. The most striking scene, involving a group organism formed by a mass of mutant ticks, is impressive, but equally implausible. A brief mention of dangerous, meat-eating squirrels threatens to turn the work into unintentional comedy.

The narrator of “Metamorphoses at the Gate” by Lysander Arden meets a strange boy his own age while on summer vacation. Returning each year, he learns more about the boy, his mother, and the cult to which she belongs. As an adult, he has multiple dreams about the boy, and the weird way in which he has been transformed.

The story has the feeling of cosmic horror, in the manner of H. P. Lovecraft. The narrator’s fascination with the boy, and the being he later becomes, is the heart of the plot. Many may find it hard to believe that the narrator acts as he does at the end of the piece.

“The Chilling Account of the Wolf-Bann of Krallenburg” by J. E. Tabor takes the form of the journal of a priest battling werewolves in the early 17th century. Complicating matters is the presence of an overly enthusiastic magistrate who imprisons and tortures suspected werewolves. The Catholic city is also facing an attack by Protestant forces. The priest and his allies fight werewolves in open warfare, and also investigate who is responsible for the curse.

The author creates a vivid and believable portrait of the time and place. There are many scenes of violence and bloodshed. The plot is a whodunit, and the revelation of the identity of the person who placed the curse involves a theme many may find overly familiar, even appearing in another story in this issue.

“The Angel Hanna” by Rodica Bretin is a brief tale in which a girl relates her experience as an orphan, when she met a fellow orphan who claimed to be an angel. Their time together leads to tragedy, and a revelation about the true nature of the girl telling the story.

This is primarily a sentimental mood piece, and is reasonably effective as such. The girl’s identity remains enigmatic, and the very last line of the story reveals that this is intentional. Readers more interested in emotion than plot will best appreciate it.

“Trapped in the Loop” by Jim Breyfogle is one of many stories about a pair of adventurers in a fantasy world. This one is different from others, as it is a war story. The female half of the pair, the rightful ruler of a conquered realm, leads troops into battle against the army of the usurper. The site of the conflict is a dangerous one, and victory depends on the enemy’s ally failing to send support, which may or may not occur.

As can be seen, the fantasy elements are minimal, except for the fact that it takes place in an imaginary land. The conclusion is open-ended, and the story reads like an excerpt from a novel yet to be completed.

In “Texas Goth” by Michael Tierney and Abraham Strongjohn, a young man kills his abusive father. During the planning and execution of the murder, a mysterious young woman appears, eventually leading him to his fate.

The author creates a grim mood, but there is nothing surprising in the plot. The final image is effective, even if it is telegraphed earlier in the story.

In “Black Sky, White Knight” by Mark Mellon, a knight barely survives a bloody battle in the dead of winter. Searching for food and a new horse, he comes across a woman at a pagan shrine and battles a fierce beast.

The descriptions are vivid, and the plot creates great suspense. Unfortunately, the story ends without a real resolution. It is unclear if the knight will triumph or will be destroyed. Perhaps the author has a sequel in mind.

“To a Dead Soul in Morbid Love” by Matthew Pungitore takes the form of a manuscript left behind by a man who witnessed his lover kill herself in an Egyptian tomb. The bulk of the text consists of his translation of hieroglyphs that tell of an undead sorcerer in ancient times.

The story is written in a lush style that reminds me of the work of Clark Ashton Smith. This is a worthy role model, to be sure, but such a style tends to lead to affectation and pretention. Readers looking for a morbid, decadent mood and poetic language will find much to admire here, but others may find it too rich a dish to easily digest.

Victoria Silverwolf has compared reading Clark Ashton Smith to drowning in opium-scented perfume.

Cirsova

Cirsova