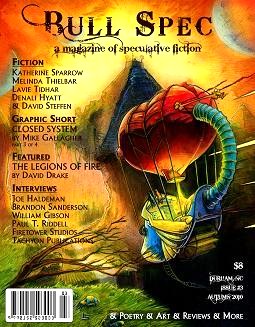

Bull Spec #3

Bull Spec #3

Autumn 2010

“The Story of Listener and Yu-En” by Lavie Tidhar

“Turning Back the Clock” by David Steffen

“Cityscape” by Denali Hyatt

“Like Parchment in the Fire” by Katherine Sparrow

“You’re Almost Here” by Melinda Thielbar

Reviewed by Indrapramit Das

In Lavie Tidhar’s “The Story of Listener and Yu-En” we are told that “This is a story about a Cat and a Dog. This is a love story. This is an adventure story. This is a sad story,” and the piece lives up to all these promises without trying to surpass the boundaries set by these expectations. Set in a distant future where humans have disappeared and cats and dogs seem to have become the primary two races on the planet, having evolved into a state advanced enough to develop and use the remnants of human civilization for their own benefit, the story tells the simple tale of airship pilot Listener (a dog) and adventurer Yu-En (a tomcat), and their quest for treasure in the more barren reaches of this world.

As is to be expected of Tidhar’s work, this is a beautifully written story with a richly portrayed setting, which I wish I could have spent more time in. The co-existing civilizations of the cats and the dogs in this exotically desolate Earth is just a backdrop, as it should be, but we see tantalizingly little of it. More time is spent on the “adventure,” their quest for treasure, which is as arbitrary as it sounds, since our two protagonists make the journey to spend more time with each other. I found the adventure itself the least compelling part of this rather lovely piece, and it’s unfortunate that it takes the reader away from the fascinating inter-species relationship between Listener and Yu-En, and their respective cultures, and instead into the more mundane landscapes of treasure-hunting stories set in abandoned wildernesses.

Told with a wonderfully lilting simplicity that makes it seem timeless, like a piece of oral folklore from the future, this is an enjoyable and transporting story. It also seems like a bit of a wasted opportunity; I couldn’t shake the feeling that Tidhar wasn’t mining the riches hidden in this world and this relationship between Listener and Yu-En. Still, their story is worth reading, and reading aloud even, perhaps. This would be my favourite pick for this issue. I look forward to more from Tidhar’s fertile imagination.

As the oddly obvious cliche that titles the story makes evident, David Steffen’s “Turning Back the Clock” is a time-travel story. These are a hard sell for me unless they involve interstellar space travel and its curious effects on what we know of time, or unless their execution is remarkable. I wouldn’t go as far as to call this story remarkable, but it is safe and well executed enough to make it a good, quick read if you enjoy time-travel yarns without anything new to say or show.

The story opens well, and keeps running at full speed without stopping to explain too much, which is its greatest merit. Without giving anything away, it’s about a pilot, a time-rift, and an event that needs to be altered. All familiar stuff, and there’s a lightly sketched out love story at the core of it all that didn’t really pull my heartstrings because we don’t get enough time to see the love between the characters involved. I also didn’t quite get the logistics behind its concept of how time-travel affects the reality of its characters; it left too many questions for me. But it’s breathlessly told, and unaffected by the weight of the many legendary time-travel stories told before it, and that might just be admirable. I remain unimpressed, but this might please time-travel fans.

Denali Hyatt’s “Cityscape” is an interesting look at a world (colonized by humans in a far-future where Earth is gone because of the sun’s expansion) that’s tidally locked to its sun and goes through no day-and-night cycles, forcing many of its inhabitants to be nomadic and travel between “day-shifts,” while others live at polar cities between day and night where the weather is mild enough to settle permanently. The “Pole Metropolises,” corresponding with second-hand memories of a lost Earth and its sedentary civilizations, becomes the unattainable ideal for our narrator, a young “Nomad” boy who is beginning to tire of his untethered life travelling between temporary homes with his parents.

There are some good ideas here; the glancing exploration of the differing cultures of the Nomads and the Metropolitans and the rift of moral viewpoints between the two; the nostalgia for a planet the narrator has never seen and barely knows anything about (Earth). Unfortunately, the story also appears a bit rushed, and too short for its own good. I never got a clear picture of why the Nomads choose to move around between the phases of day on the planet, aside from the climate being too uncomfortable to stay in one place too long. Why choose travelling huge distances constantly over moving to the Pole Metropolises, and why the Nomads’ “disapproval” of those who have (wisely) settled there? It perplexed me. I didn’t understand what the Nomads do to survive either; where they get their food from, etc. There were other things that bothered me too; the story is set in such an incredibly distant future that the sun has swallowed the Earth, and yet the colonists use cars and seem quite similar to present-day humans. It’s mentioned that the people of this planet have been to Earth once, and yet they seem quite irrevocably stuck on their world, with no mention of space travel (or even atmospheric flight) capabilities or the implications thereof. Just on a cosmic timescale, it doesn’t seem at all possible for them to have visited Earth while humans were still living on it if Earth went through its death throes since their last visit (the sun will make Earth uninhabitable for millions of years before actually destroying the planet). Also, if the family is moving “towards the sunlight,” as they are when we start the story, it stands to follow that they were in night before this story, and raises the question of why they’d be in night in the first place, as it’s established that the night-side has too harsh a climate for anything to live or grow in.

I found the descriptions of the journey from evening to afternoon compelling, and the narrator’s voice is convincing, as is his plight. But the many questions I had muddled the whole experience of reading the story, on the second go-through especially. The action the boy takes towards the conclusion is also abrupt and selfish, followed by quick, pat explanations of why it isn’t selfish, which might have worked if they had been worked into the story organically. I feel that this story was a great idea which wasn’t allowed the time to really grow into the story it wants to be. Hyatt shows promise as a writer, and I’ve no doubt that she’ll get the chance to develop more with her following works. As such, a promising debut story, but one that ideally should have been better thought-out and worked on longer.

Katherine Sparrow’s “Like Parchment in the Fire” isn’t quite a time-travel story, but one that cross-cuts between mid-seventeenth-century Surrey and late-1960s San Francisco, following Winstanley, the founder of a communal movement towards free food distribution (dubbed “Diggers” by their persecutors), and Berg, one of his twentieth-century acolytes struggling to keep his word alive just as disillusionment kicks into the hope fostered by the ’60s. This is a good story, confidently written and told, with effective thematic undercurrents that make it universally relevant.

I liked the convincing period details in both settings, and the distinct variance in voice between the two temporally separated narrators. The speculative element is closer to magic realism than anything else, with the two men occasionally glimpsing each other across the gulf of time. Sparrow makes rewarding use of the intercutting to bring out the parallels between the persecution the Diggers face in the seventeenth-century for their outlandish ideas, and the persecution Berg’s New Age contemporaries face for theirs. Poignantly, the story is elegantly steered by Sparrow into a fictional treatise on the perseverance of hope in the face of brutal and inexorable disillusionment, and the reconciliation of faith (not spiritual, but ideological) with failure and disappointment. To say nothing of what happens, the story brings together the Winstanley and Berg in a way that doesn’t disappoint, and doesn’t make it all appear too gimmicky.

I had some quibbles with Berg’s narration, which makes the events of the parade where part of the story takes place confusing at times, but then again this might have been intentional. The last few paragraphs also try a bit too hard to sum things up, betraying the thematic effectiveness of most of the piece, despite occasional close brushes with didacticism or obviousness. But overall, this was well worth the read.

Melinda Thielbar’s “You’re Almost Here” is a short satirical look at a not-too-far future that is both eminently plausible and rather disturbing (according to the story) for art and society. It’s an engaging glimpse into a familiar yet new world that uses our own present-day ‘futuristic society’ as a foil. Thielbar writes gracefully quick and evocative prose that grounds this reality and lets the reader inhabit it easily, perhaps helped by the second-person viewpoint. It’s also often too obvious in its satire and indictments of contemporary society and its culturally cannibalistic consumerist inclinations (the futuristic advertisements are an example).

“Nothing in your life has equipped you to have an original thought if you had one,” we are told, and this sums up the story’s view of the modern world. It’s an effective line, to be sure, but is it enough to just point that out? Perhaps that’s for the reader to decide, because ultimately the story indicts its own narrator (and writer) as well as its hypothetical reader, for being a part of the future that we’re already on our way towards. Unsubtle, but a clever use of the second-person, and a thoughtful read.

As has already been mentioned in our review of issue #2, Bull Spec is an impressively slick magazine with great production values, and it’s off to a promising start. This issue has interview articles with Joe Haldeman, William Gibson, Paul T. Riddell and David Drake (with an excerpt of his novel The Legions of Fire). It also includes selections of poetry, reviews, and a short-comic by Mike Gallagher (part of a serial). Also features some nifty art, including the colourful cover by Jason Strutz (which is an illustration for Lavie Tidhar’s short story). This magazine deserves a long life, but I have to agree with Rena Hawkins in her review of the last issue; I hope more space is devoted to short fiction so that the stories they publish have more time to develop, because at the moment several seem shorter than they should be.