Edited by

David Farland

(Galaxy Press, April 7, 2020, Tpb, 450 pp.)

“The Trade” by C. Winspear

“Foundations” by Michael Gardner

“A Word That Means Everything” by Andy Dibble

“Borrowed Glory” by L. Ron Hubbard (reprint, not reviewed)

“Catching My Death” by J. L. George

“A Prize in Every Box” by F. J. Bergmann

“Yellow and Pink” by Leah Ning

“The Phoenix’s Peace” by Jody Lynn Nye

“Educational Tapes” by Katie Livingston

“Trading Ghosts” by David A. Elsensohn

“Stolen Sky” by Storm Humbert

“The Winds of Harmattan” by Nnedi Okorafor (reprint, not reviewed)

“As Able the Air” by Zack Be

“Molting Season” by Tim Boiteau

“Automated Everyman Migrant Theater” by Sonny Zae

“The Green Tower” by Katherine Kurtz (reprint, not reviewed)

Reviewed by Victoria Silverwolf

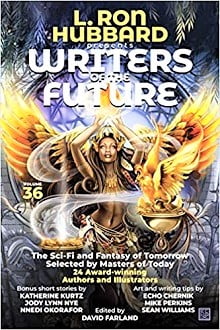

As in previous years, the latest volume in this popular and long-running series features prize-winning stories and illustrations from new writers and artists. As bonuses, it also offers reprinted fiction from the founder of the contest, a previous winner, and a current judge, as well as essays on writing and illustration, and a new story from an experienced author, inspired by the book’s cover art.

In “The Trade” by C. Winspear (illustrated by Arthur Bowling), an alien in human form appears at the International Space Station. The extraterrestrial offers humanity technology that will transform Earth into a paradise, but only at a very high price. The narrator must decide whether the bargain is a fair one, and makes a choice that will have an extraordinary effect on her own life.

The premise is an interesting one, and raises the eternal question of whether the good of the many is worth the sacrifice of the few. Although the alien possesses extremely advanced abilities, it appears in most ways as a very ordinary human being, not always to the benefit of the reader’s sense of wonder. A long list of the technologies offered by the extraterrestrial and the exact price of each item interrupts the narrative, which slows the story’s pace considerably.

“Foundations” by Michael Gardner (illustrated by Aidin Andrews) is a surreal fantasy in which a family’s ancestors become part of their house. The story begins when the narrator fails to keep an eye on her young sister, allowing an uncle to trap the child in the house, as he attempts to escape into the outside world. The narrator faces the dilemma of either allowing her sister to remain a part of the house forever, or freeing her at the risk of destroying the house and the family business.

The author makes use of a unique concept, and creates an appealing character who feels responsible for the crisis threatening her family. The ways in which relatives become part of the house, and what effect this has on the family business, are not always clear.

“A Word That Means Everything” by Andy Dibble (illustrated by Heather A. Laurence) features a Christian missionary and linguist who attempts to translate the Bible into language that squid-like aliens can understand. When he tries to cancel the project, believing the extraterrestrials are not truly intelligent, his superiors send a famous evangelist to aid him. Complicating matters is the fact that the aliens are extreme solipsists, each one believing itself to be the only entity in the universe, and that the humans exist only in its imagination.

Much of the story consists of a discussion between the two human characters about the multiple meanings of the word logos, which seems more appropriate for a theological essay than a work of fiction. The plot reaches a climax during an encounter with deadly predators, striking a jarring note in an otherwise quiet, philosophical story.

The title of “Catching My Death” by J. L. George (illustrated by Kaitlyn Goldberg) is literal. In this version of the modern world, people go into a forest when they reach adolescence and hunt for strange beings that determine when they will die. They hope to catch so-called good deaths, which ensure them long lives. Those who catch bad deaths fail to obtain decent education and employment, because society knows they will die soon.

The narrator winds up with a bad death, and makes a desperate effort to steal a good death from another person. Meanwhile, a movement arises to end this tradition, even though those who fail to hunt for their deaths are outcasts.

The author develops the premise in a logical fashion, making a fantastic notion seem plausible. The story serves as an allegory of social class and the way it determines one’s future. The reader may wonder how this way of life (and death) came about in the first place, since it is so obviously arbitrary and unfair.

“A Prize in Every Box” by F. J. Bergmann (illustrated by Ben Hill) involves a brand of cereal that comes with bizarre, magical objects. In particular, a strange kind of remote control, that can work its wonders on anything, changes the lives of a group of children. Among its many effects, it heals a boy afflicted with cancer, and metes out punishment to a pair of bullies.

There are few surprises in the plot, as it is obvious that the dying child will regain his health, and that the bullies will pay for their crimes. These two subplots render the story episodic. In essence, this is a tale of wish fulfillment, best suited for younger readers.

The nearly universal wish to change the past is the theme of “Yellow and Pink” by Leah Ning (illustrated by Irmak Çavun). The protagonist relives the past multiple times, in an effort to prevent his wife from dying in a car accident. Because the technology required to do this is extremely expensive, he murders the same wealthy man repeatedly, in order to obtain the necessary device every time he tries to change fate. He eventually realizes his quest is futile.

The method by which this peculiar form of time travel works is unexplained, leaving the reader with many questions. It is clear from the start that the protagonist cannot save his wife, so he seems both foolish and immoral when he kills his victim several times.

Unlike the other original stories in the book, “The Phoenix’s Peace” by Jody Lynn Nye (inspired by the cover art of Echo Chernik) comes from the pen of a seasoned professional. This fantasy adventure takes place in a land where a phoenix reincarnates whenever war threatens the realm, bonding with one of the priestesses who serve in its temple. For the first time in history, the previous phoenix left two eggs in its nest instead of one when it died in flames. When a neighboring country that wants to obtain the second egg attacks, the reason for the double miracle becomes apparent.

Much of the story involves a romance between the protagonist and a visitor from the bordering land. Unlike the exotic and sophisticated fantasy aspects of the plot, this part of the tale seems naïve and adolescent. The nature of the second egg, although dramatic, is predictable. The sudden appearance of firearms late in the story, although otherwise the setting seems to be one of low technology, is disconcerting.

“Educational Tapes” by Katie Livingston (illustrated by John Dale Javier) takes the form of a series of recorded instructions. These direct the listener to either accept or decline an offer from the government. Slowly the reader learns that the listener really has no free choice, and will face severe consequences if she declines and sets out to find the ocean that the government denies exists.

This brief synopsis only offers a hint of what this complex story involves. The narrative style is nontraditional, reminiscent of New Wave science fiction. Often the government tapes contradict each other, or say one thing while implying something quite different. This extreme example of an unreliable narrator requires careful reading, which is well rewarded by the rich imagination and psychological depth of a profound examination of a dystopian society.

“Trading Ghosts” by David A. Elsensohn (illustrated by Mason Matak) mixes science fiction and fantasy. Ghosts and fallen angels exist, in a far future of galactic exploration. The narrator is a former starship captain, whose lover died in an accident in space. He agrees to help a fallen angel die. This requires journeying to a planet inhabited by a woman who can destroy an angel. The quest allows the narrator to accept his feeling of guilt for the death of his lover.

The main appeal of this story is its unusual blend of genres, although they do not always meld effectively. The ghosts seem to be a symbol of the narrator’s remorse, but otherwise they play no part in the plot.

In “Stolen Sky” by Storm Humbert (illustrated by Anh Le), aliens entertain humans with music, poetry, and other art forms. The narrator is one such extraterrestrial, newly arrived on a human colony world. In conversations with other alien artists, it becomes clear that human beings, although kind and appreciative, take something vital away from the beings whose work they admire.

This is a gently melancholy story, beautifully written, with many poetic descriptions. It addresses the issue of cultural appropriation in a calm and thoughtful manner.

The two main characters in “As Able the Air” by Zack Be (illustrated by Brock Aguirre) are a military drone and the man who commands him at a distance, through telemetry. Together they work to defuse mines at night, on a planet where an endless war rages during daylight hours. The man faces reprimand for treating the drone like a fellow soldier, instead of an expendable piece of machinery. Meanwhile, he relieves his stress and loneliness on the war-torn planet through a long-distance relationship with a lover, leading to an ironic conclusion.

The author has a gift for characterization, and the futuristic setting is convincing. The story’s resolution depends on a twist ending, which may seem gimmicky to some readers.

“Molting Season” by Tim Boiteau (illustrated by Daniel Bitton) takes place after aliens arrived on Earth, leading to mass suicide. Without explanation, a young woman shows up in the room of a man who works the graveyard shift at a nearly deserted inn. He finds her asleep each night that he works, and gone when he returns. They finally meet when both are awake, and he learns about her obsession with the aliens, their peculiar form of reproduction, and the reason they came.

This is a strange story, less linear and coherent than a short description makes it sound. It creates an odd mood, both eerie and passive, as if its human characters have come to treat the bizarre world in which they live as perfectly normal. At times, it seems as incomprehensible as examples of alien literature that appear in it.

“Automated Everyman Migrant Theater” by Sonny Zae (illustrated by Phoebe Rothfeld) adds a touch of comedy to an anthology full of serious fiction. A troupe of traveling robot actors attempts to impress a robot theater critic by putting on a production that tests the limits of what people allow machines to do. Chaos ensues, leading to the uncovering of the critic’s secret.

This is a light story, full of puns and slapstick. The humor is often sophomoric, and references to a recent film and a glamourous actress of the present day mean that it will date very quickly.

Victoria Silverwolf is amazed that there are so many talented writers and artists out there.

Writers of the Future #36

Writers of the Future #36