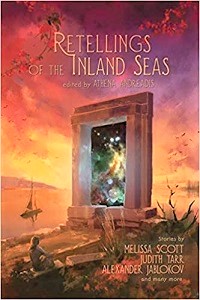

edited by

Athena Andreadis

(Candlemark & Gleam, June 2020, tpb, 284 pp.)

“Into the Wine-Dark Sea” by A.M. Tuomala (poetry; not reviewed)

“Sirens” by Melissa Scott

“Hide and Seek” by Shariann Lewitt

“The Sea of Stars” by Genevieve Williams

“Between the Rivers” by Judith Tarr

“Calando” by James L. Cambias

“One Box too Many” by Christine Lucas

“The Fury of Mars” by F. J. Doucet

“Out of Tauris” by Alexander Jablokov

“Little Bird” by Kelly Jennings

“Wings” by Elana Gomel

“The Crack at The Border” by Dimitra Nikolaidou

“Unearthing Uncle Bud” by Athena Andreadis

Reviewed by Tara Grímravn

Greek mythology has, as I suspect it has done for many, stoked the roaring fires of my imagination ever since I learned to read. So, when I was assigned Retellings of the Inland Sea, I was quite thrilled with the opportunity. While some might be tempted at first to skip over Andreadis’s “Ancestral Campfire, Distant Beacons,” an editorial that acts as the introduction to the anthology, and get right to the reading, I recommend refraining from doing so. It serves as an engaging backdrop for the twelve stories (and one poem) that follow it, themselves a fresh reweaving of threads plucked from familiar myths. From fallen angels to wormholes in space, there’s something to please everyone in this anthology.

“Sirens” by Melissa Scott

Perseis is a Firstborn in charge of Aptera, a space station located somewhere in the far reaches of space. Not long ago, she’d taken in the crew and captain of the ship Nostos, themselves on the run from something called the Event, a destructive force unleashed by rogue artificial intelligence. Knowing that the Event may soon arrive at their doorstep, Perseis and Captain Harsharin must find a way to get everyone to safety on the planet Ithaka, even if it may only be a temporary haven from the Event.

Based on the myth of the fall of Atlantis, the world in which this story is set seems like it would be quite complex, yet almost nothing is explained to clue the reader in. As a result, it is very difficult to orient oneself within the tale, which reads as little more than a jumble of futuristic jargon overlaid on an SF storyline. For example, the notion of Firstborn and Secondborn humans is ever-so-slightly touched upon but not enough to let the reader understand the difference, why those differences matter, or how human society is now structured.

The same goes for whatever the “adjacent possible” might be—it’s mentioned frequently enough but no attempt is made at making the reader understand what it is, even when Perseis and Harsharin are in it. Based on the way it’s treated in various passages, it could be a form of psychic, energetic, or mental plane on which the AI operates or it could be the space through which space/time travel is made possible. Unfortunately, it’s not at all clear which it happens to be. Granted, there seems to be an attempt at inference but this, too, isn’t well done. Frankly, I found this piece to be a rather boring and unnecessarily convoluted plod through muddy waters.

“Hide and Seek” by Shariann Lewitt

Penna works as a navigator aboard a spacecraft that is in less-than-stellar condition traveling through the Kuiper Belt. As soon as she gets the navigation computer up and running, the display shows an asteroid that looks suspiciously like it could be an abandoned ship. Ordered by the Commander to set a course straight for it, she willingly obliges, if only to sate her own curiosity. The only question now is who or what built it and whether they’re still in occupancy.

Lewitt’s story, based on the part of Homer’s Odyssey that details Odysseus’s encounter with the cyclops Polyphemus, is very well-crafted. If Andreadis’s goal was to choose stories that take the spirit of familiar myths and rework them into something new and shining, this is a great example of her success in that regard.

Make no mistake—this is not a simple retelling of Odysseus’s crew and Polyphemus. The clues are there if you know where to look, to be sure, but this is an entirely new animal unto itself. The style in which it’s written, the vernacular with which Penna tells the story, the snippets of history we’re given, all of these add up to create engaging characters and a vibrant setting. The story itself was also quite entertaining. It certainly kept me reading straight through to the end.

“The Sea of Stars” by Genevieve Williams

With the days of the Argonauts far behind him, Euphemus once again finds himself in peril. He had tried to dock his ship, Kyrenia, in Athens but discovered that plague was running rampant through its streets. Fearing for the safety of his crew, they quickly set to sea again only to have a storm to chase them onto the shores of a bleak, uninhabited island where the ship founders on the rocks. With a mutiny near at hand and rations running low, Euphemus is desperate to find a way home. Unfortunately, the only thing any of them have found thus far is a strange, metallic, flower-shaped object of unknown origin.

Another story inspired by Homer’s Odyssey, this time being Odysseus’s descent to Hades, this one, too, is very good. Like the previous tale, it’s entirely unique; a fresh re-imagining of the hero’s conversations with the spirits of the dead. The bleakness of the landscape and the rising tension between the remaining crew and Eupehmus is palpable in each sentence. It’s very much worth a read.

“Between the Rivers” by Judith Tarr

Negar steps off the artificially intelligent ship Ninsun and takes in the sight of the newly settled planet before her. As one of the Family (a group of enhanced and modified humans that govern the rest of humanity across the universe), she’s been sent here to guide the people of this new planet as they build their civilization. But, as the old saying goes, absolute power corrupts absolutely, and Negar soon falls prey to hubris, going so far as to take every possession from the people, including forcibly recruiting workers for her palace and demanding the “right of first night” on all marriages. Realizing that it’s arrogant charge has strayed far off the course that was her original purpose, the ship Ninsun creates a clone of Negar, hoping it will be able to set things right. Unfortunately, the clone escapes before it’s had a chance to fully develop. All Ninsun can do now is let it develop on its own however it may, with the hope that it will one day put a stop to Negar’s tyranny.

Tarr’s story takes a slight deviation from the familiar Greek tales and delves into Sumerian mythology with the Epic of Gilgamesh. It’s interesting to note that the title acts as a double reference: on one hand, the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, the land between which was one of the cradles of civilization, and the two rivers the crew find on the largest continent of their new planet. While there’s no flood in Tarr’s tale, there’s still the familiar ring of a god turned against those she was meant to protect and her undoing in the form of someone connected by blood. Great story!

“Calando” by James L. Cambias

In a rather unfortunate turn of events, the well-known singer Ari now finds himself hurtling towards the surface of Neptune with nothing more than his spacesuit to shield him. Just a short while earlier, he’d been discussing his upcoming performances with Panna, a researcher sent out to Neptune to research feral bioships—ships that had been created as living organisms that could heal, grow, and reproduce on their own. Now, without warning, he finds himself and Panna suddenly tossed out the nearest airlock by hijackers. As Ari ponders his imminent death, something in the distance catches his attention—a beacon of hope, perhaps?

Reading this story, it’s easy to see the influence of the original myth about Arion & the dolphin. The story, though set in some distant future in space, follows the older storyline closely. I can’t say too much about this tale without giving away the plot, but I will say that, while I enjoyed the story overall, I felt it left a loose end or two in regards to Panna that needed to be tied up. Otherwise, it was a good read.

“One Box too Many” by Christine Lucas

Sentenced to three years of hard labor on Mars, Penelope works in a station serving under the command of her older sister, Sophia, and processing samples from various places across the solar system. This time, it’s an alien artifact the size of a Rubik’s cube. Just touching it sets the nanobots in Penelope’s head on high alert. As the sisters try to figure out just what this box is, they also wonder just what dangers it might release, should they succeed in opening it.

As much as I was looking forward to a tale based on Pandora and Epimetheus, I have to say that I don’t feel the storyline’s execution is well-thought out. The hook is interesting enough—I was certainly pulled into the story from the beginning—but when it comes to the details, those were very poorly planned out, introduced, and explained. For example, in explaining the Panacea code and the backstory on Penelope, it gets confusing. At the first mention of a Dr. Edhi, it’s unclear whether this is another person or Penelope herself. The content of the same paragraph seems to indicate that Penelope is Dr. Edhi, but then it’s later established that she was an analyst working for Edhi. The clues building the tension between Penelope and her sister are also not very well-spaced throughout the story. For the first few pages, they seem fine, then suddenly we’re informed of the contempt Penelope has over her sister ratting her out. The seeds of this discord should have been more evident much earlier. There also appears to be missing dialogue in places. Overall, it’s an okay story, but one that most definitely needs a bit more polishing.

“The Fury of Mars” by F. J. Doucet

Born on Earth, Aguta had been taken to Mars by her father, leaving her mother, the famous singer Isla Agnes Iversen, behind. She’d grown up thinking it was because her mother was unstable and thus indirectly responsible for the death of her younger brother some sixty years ago. Now a Martian judge in her late middle-ages, she finds herself face-to-face with Isla, who has gotten herself into legal trouble on Mars for accidentally killing a young man in an auto accident. Instead of declining to hear the case due to conflict of interest, Aguta decides that she’s impartial enough to judge Isla, who she considers lesser and beneath her. She then sentences her mother to one day of illusionary punishment during which the elderly woman will be forced to endure what amounts to seventy years of psychological torture using her own worst memories. When misfortune befalls Isla just ten minutes into the punishment, Aguta’s life begins to unravel as she becomes aware that something otherworldly seems to be stalking her.

Doucet’s story is based on the legend of the Erinyes, three goddesses of revenge who take delight in punishing those who have committed murder, especially familial murder, and other crimes. The story does an excellent job of re-imagining the legend and fitting it into a futuristic landscape on Mars. The plot twist is just ever so slightly predictable, as it is easy to guess early on what the outcome will be for Aguta, but it’s a great read nonetheless.

“Out of Tauris” by Alexander Jablokov

Iphigenia watches as the shape of a man appears in the distance. She knows why he comes; all men come to the Temple of Artemis at Vravron for the same reason. His wife has died in childbirth, and he carries her blood-stained clothing here so that the goddess may wash away the pain of his grief. When he offers a sacrifice to Iphigenia, recognizing her as the daughter of King Agamemnon and priestess of Artemis, she tells him to hold his offering until she tells him the story of how the goddess came to be here at Vravron.

Anyone familiar with Greek myth will recognize the story of Iphigenia Atreides. Her father, King Agamemnon, had insulted Artemis by killing a deer in her sacred grove and boasted about it. When the goddess demanded a sacrifice in kind before he could take the city of Troy, he offered up his daughter Iphigenia. Some versions of the myth tell how Artemis snatched the girl away at the last moment to serve as a priestess in her temple at Tauris. It’s this version that Jablokov has used as the foundation for his story. He doesn’t follow the tale to the letter, though, and that makes for a very engaging reimagining of the myth. The end is poignant and touching, and I sincerely recommend readers give this one a read.

“Little Bird” by Kelly Jennings

Kidege is a gymnast for Walker House. Some time ago, she broke her leg in training and was given to Melia, a potential heir to the Primary Board Seat of Walker House, as a bonded worker. As time passes, the two become as close as sisters. When it is announced that Melia would wed Tiru Kadir Walker of Kadir House, Kidege goes with her to meet her intended. They are wed a few days later. Tensions rise as Melia’s personality appears to change, and the situation in which Kidege finds herself grows ever more perilous.

Jenning’s story is based on the myth of Philomena, who legend tells us was turned into a nightingale after being raped and disfigured by her sister’s husband. This is another excellent retelling. Jenning has taken the essence of the source myth and turned it into a very entertaining story about the lust for power, loyalty, and justice.

“Wings” by Elana Gomel

Psyche wanders the zones of the world, searching in vain for her husband and daughter, Eros and Hedhoné, as she carries out the tasks set for her by her cruel mother-in-law, Aphrodite, who harasses her each step of the way. One evening as she takes cover from a flock of monstrous pigeons sent to torment her on her journey, she finds herself falling into darkness only to wake later on a beach. A soldier approaches her, and she tells him her story as they walk the shore together. As she soon reveals, the happy marriage between Eros and Psyche, the one blessed by the gods and with which he is so familiar from myth, was not the end of her story.

This tale begins long, long after Zeus forces Aphrodite to stop her cruel persecution of Psyche and allows her and Eros a legitimate marriage. In the telling, Gomel presents a fascinating premise—what if Aphrodite was the only deity left in charge after the other gods had died? It’s a captivating discussion of how the old ways, persecuted and abandoned, give way to the new religion under the brutal rule of a single petty and jealous deity. I really enjoyed this one.

“The Crack at The Border” by Dimitra Nikolaidou

Nineteen years ago, our unnamed narrator lost a friend who had been shot and killed after crossing the Green Line, a boundary dividing the Greek side of Cyprus from the Turkish side. Now, she has returned to lead the dead boy’s wandering soul to the afterlife.

One of the shorter tales in this anthology, Nikolaidou’s story is based on the god Hermes’s role as a psychopomp, a spirit that leads the souls of the departed to the other side. In this case, though, this tale has less to do with deities and more to do with the human experience of loss, war, and finding peace. It’s short, bittersweet, and highly recommended.

“Unearthing Uncle Bud” by Athena Andreadis

Danny Fenton comes from a long line of screw-ups plagued by bad luck. With her mother dead, she’s the only family member left able to look after her mother’s youngest brother, Uncle Bud. While he’s always been a bit strange and often in trouble, mostly for benign things like breaking into an observatory to use the telescopes, today is the final straw. Danny’s just received word from the local electric company that a drain on the city’s infrastructure has been traced to her uncle’s home, and the authorities are on their way to arrest him. Racing the clock in order to beat them there, she’s not at all prepared for what she finds.

According to the key at the end of the book, Andreadis’s story is based on the mythological figures Daedalus and Penelope. The two are from very different myths, Daedalus being the renowned inventor who created the minotaur’s labyrinth and Icarus’s wings, while Penelope was the wife of Odysseus. Andreadis gives us a skillful blending of the two into something wholly new and original. The ending wasn’t quite as satisfying as I’d have liked—it felt a little like there should have been more—but it was still an enjoyable read.

Retellings of the Inland Seas

Retellings of the Inland Seas