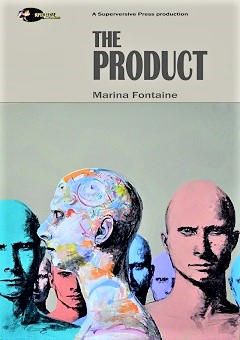

by Marina Fontaine

(Superversive Press, October 2016, pb, 92 pp.)

Reviewed by Seraph

I was very excited to review one of the first offerings by Superversive Press. Allow me to begin by giving a brief introduction to the Superversive movement, as it is a somewhat recent development in literary circles, and not all readers may yet be familiar with it. In their own words, “Superversive Press is a new small press that aims to publish Superversive Fiction and is an outgrowth of the Superversive Fiction movement that aims to tell stories that are uplifting and ennobling. Heroes that are heroic, beauty that is beautiful, the transcendent that is transcending, stories that say virtues are real, and that Civilization triumphs over barbarism.” To delineate further, let me add that “superversive,” (as defined by one of the movement’s founders, John C. Wright, courtesy of his wife L. Jagi Lamplighter), goes as such: “You know how subversive means to change something by undermining from below? Superversive is change by inspiration from above.” I’d like to add, in my own words, that the Superversive movement represents a shift away from recent trends in science fiction and fantasy that have resulted in overly dark and preachy fiction that can leave a reader feeling punished simply for having read the stories. By this I mean that the world is, and always has been, a chaotic and frightening place, on a scale that dwarfs the comprehension of most minds. All the negative that anyone could ever desire, if they indeed desire such, can be found in history books and the nightly news, and can be quite overwhelming when not balanced by stories of hope and virtue. While I do not suggest that literature should not sometimes reflect the darker nature of humanity and life, I am comforted and excited that there is an effort to elevate literature above the muck and grime. There is a place for literature which aspires to create hope and condemns despair as much as there is a place for gritty realism.

In that vein, and with no further introduction, the review.

The Product takes place in the near future, presumably in the US, although the exact timeframe is unclear, and really, the location is vague enough that perhaps I’m simply seeing my own country of origin in the mirror. There are numerous similarities to our own time, especially in terms of things like technology, vocabulary, and environment, but it is not concurrent with our own timeline, inasmuch as the government has all but completely succeeded in stifling all free will, individuality, and for the most part even personality. The descriptor of drones is used frequently, and does not seem to be an exaggeration or over-simplification. Those it refers to are typical of a dystopian society: emotionless and apathetic, physically deprived and inferior, and seemingly capable of taking delight only in the suffering of others. The lack of independent thought and mindless savagery is striking, and is present in far more concentration than a lot of other stories in this genre. This story approaches alternating levels of bland apathy and vicious voyeurism seen only in the darker realms of dystopian fiction. Concepts like Re-ed (re-education) and Enforcers (brutal thugs, read: bullies on steroids) are common to dystopian fiction, as is the damage caused by living in fear that any slight word or action not in conformity will subject the individual to torture, abuse, and re-programming unthinkable, even in all but the most devolved corners of modern societies. The contrast is only made more severe by how personable and relatable the main characters are. “Users” are those who have sampled the product, and “dealers” are those who risk life and limb to bring it to them, not unlike the nomenclature of the drug world in modern society.

The main characters consist of three Dealers and one User, who are survivors of a system designed and apparently quite successful at crushing the souls of those within its grasp. The protagonists are split evenly, two male and two female, which flows nicely as far as how the four of them interact with each other, and offers varying pictures into how both sexes cope and survive in such hostile conditions. Kevin, the first of the four to whom we are introduced, is defined mostly by his determination and force of will, as shown on multiple occasions when he is subjected to abuse that would break most people I’ve ever met, yet he never yields. He approaches that chasm several times, as would anyone, but it is his force of will that keeps him from plunging headfirst into despair. Let me be clear: regardless of Hollywood interpretations, there are many unspeakable things that one human may do to another, and no one can remain unbroken forever. I appreciate how the author acknowledged this, from Kevin’s perspective, without ever giving up hope. It’s a delicate balance, and the author conveys it well. There is the knowledge and trepidation of what is to come, and the inevitability of a fate far worse than death should the Enforcers succeed in dragging him to their compound, but through it all he faces every moment with strength and conviction.

The second of the four is Lily, Kevin’s girlfriend, and the one User amongst the Dealers. She is refreshingly less hardened than the other three, surprisingly innocent and virtuous in a place where such things are by all rights impossible. There is a moment much later in the story where she finds a flower, growing healthy and free, hidden in amongst the larger weeds, that sums her up perfectly. The flower is a daylily, for which her mother named her, and the joy it brings is that of simply knowing that such a thing is possible. It is the joy of hope. It’s also appreciated that she isn’t portrayed as helpless. This is not some mockery of the virtuous, or some weeping damsel, but someone who has before now not truly walked through the fire, and when she finds herself in the flames, rises to find strength in herself, and acts in the face of danger. One criticism that seems to be constantly flung at the Superversive movement is that traditional SF/F objectifies women, being nothing more than helpless damsels waiting to be rescued by overly macho heroes, and thoroughly objectified as sexual prizes to be won in some meaningless contest of toxic masculinity. Lily is a wonderful example of how false those accusations are. Not only does she rise to action in defense of Kevin on several occasions, but she remarks casually about her proficiency with guns, and hesitates not in the slightest to put her life on the line for others, even strangers she has never met. This is a woman who refuses to be a victim, even when victimized. She is portrayed not as demanding love or sexual affection, but as being worthy of it. Not as an object of sexuality, but as an individual worthy of the love Kevin holds for her.

Justin is the third of the protagonists we meet, and is the dealer boyfriend of the fourth dealer, Gina, who is Kevin’s ex. The two of them are both gritty realists, but they are such in their own ways. Justin is quiet, reserved, with a core of tempered steel, both a tortured soul and a healthily masculine hero wrapped up in a grimly experienced visage. He reminds me of many veterans I’ve known. Haunted by the reality of things he has lived through, things he has had to do simply to survive, but resolute and full of life all the same. He is easily my favorite character, and the one that resonated most with me on a personal level. This is the sort of man I aspire to be, and hope I have become. Gina is beautiful and happily sociable, which belies the grim determination and raging fire within her soul. While perhaps not entirely rational, and indeed sometimes simply rash, her heart is always in the right place, and she follows it with the strength of her body. This is someone who can not only keep up with Justin, but push and challenge him. She manages to be feminine and sexual without ever devaluing herself, and it never defines her. It’s nice to see a woman who is defined by the virtue and strength of her soul, while being accentuated by her beauty and allure, as opposed to many so-called feminist icons, who are defined by their sexuality and allure, and are accentuated by the lack of virtue and weakness of their souls. Gina is a woman anyone would be thrilled to call a friend, but even more importantly, a woman anyone would be thrilled to have covering their six. The Product itself, which seems to have remarkably transformative properties, is none other than music. For those who doubt the legitimacy of the transformative power of sound as rivaling that of a drug, I suggest a wide array of literature and science on the subject.

All in all, this is a well-paced, descriptive offering that upholds the intent of both its publisher, and movement. The best advice I can offer is to approach it without the baggage of previous prejudices or bias, and simply enjoy it for the story it is. It is not as lengthy as many other dystopian stories tend to be, which may be the result of being an early offering, but personally I find it to be something of a blessing, insofar as it accomplishes its goals and doesn’t overly linger in an attempt to do too much. I recommend it to anyone, and I specifically recommend it to anyone who is looking for fiction from the Superversive movement, or who is interested in finding out what it are all about.

The Product

The Product