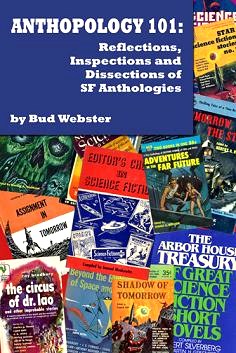

Reflections, Inspections and Dissections of SF Anthologies

by Bud Webster

Introduction by Mike Ashley

(The Merry Blacksmith Press, 2010, 328 pp.)

Reviewed by Indrapramit Das

When Tangent’s editor-in-chief Dave handed me Bud Webster’s Anthopology 101 (figuratively speaking; he mailed it to me), he told me he was convinced that I would, as a writer of sf, and a pursuer of sf knowledge, both learn a lot from and love this book. Obviously, Webster’s book isn’t entirely a recent release, having been published in 2010. One can’t begrudge an editor occasionally wanting his staff to review a book to increase its exposure; this is a useful way to stimulate the genres we love by hopefully pairing new readers with books they’ll recognize as right for them.

And since I know Dave’s a true believer, a devout fan of sf/f with experience, knowledge and devotion far surpassing my own (and I do consider myself an ardent acolyte of the genre), I had no reason to doubt his assertion that I’d love Webster’s compendium. So I’m rather interested in the response I had to the book. That is to say, I didn’t love it. Often, I didn’t even like it. I did learn from it. A lot.

And since I know Dave’s a true believer, a devout fan of sf/f with experience, knowledge and devotion far surpassing my own (and I do consider myself an ardent acolyte of the genre), I had no reason to doubt his assertion that I’d love Webster’s compendium. So I’m rather interested in the response I had to the book. That is to say, I didn’t love it. Often, I didn’t even like it. I did learn from it. A lot.

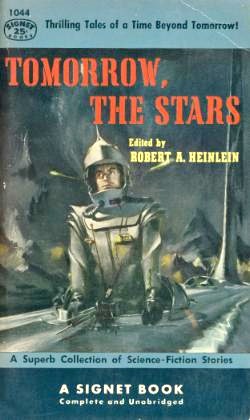

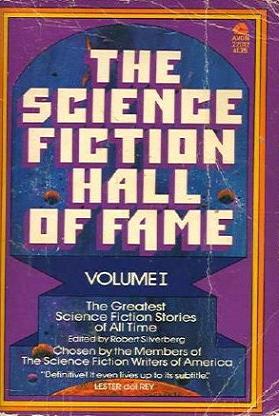

Anthopology 101 does much of what it sets out to do; that is, provide an extensive and useful index of classic science-fiction anthologies and their contents. Webster’s love for the genre, and for the unique form of the anthology (both reprint and original), wafts off this book like cheese-scent off a pizza-box. As a result, you’ll find your own appetite for the genre stoked. His passion and delight for the medium will likely prove infectious for any fan of sf reading him. I know I felt like seeking out many of the items in his lists of exotically aged repositories of sf short fiction from the ages. Indeed, I felt inspired enough to actually (seriously) try my hand at being an anthologist, reading his sometimes fascinating profiles of legendary anthologists like Frederik Pohl, Groff Conklin, Judith Merril and Robert Silverberg.

The problem that I found here is that I didn’t like the writing, and the method. The book is a success as an index of sf anthologies, but I wanted more than that. I wanted a book, not a list. Much of these articles (18 of the 25 reprinted from Webster’s eponymous column for the SFWA Bulletin; the initial 7 columns appearing first in a trio of other venues before landing a permanent home at the Bulletin) have too little substance, merely going over the contents of the anthologies with a clear love for them, but little actual insight. It doesn’t really make for good reading when the articles tell you that a story’s excellent or not that great, but deigns to elaborate in any way on such a statement. Too often, Webster’s articles are filled with lines like “Better than I have tried to describe [this story], and I won’t even attempt to, but it was a remarkable story when it appeared in 1934 and it remains an affecting, evocative story.” (p.73). Personally, that tells me nothing, and leaves me thinking that in such cases, Webster should just leave the list of stories in and exclude any commentary.

Consequently, the book is at its best when Webster goes into more detail, going beyond indexing to actually give us a picture of the people involved behind the colorful covers of these anthologies, or distilling the essence of the stories in these volumes. For example, in the article “The Non (Final) Stage” (p.103) Webster paints an insightful and balanced portrait of the late Carol Rinzler, editor-in-chief of Charterhouse, and one of the guiding hands behind the botched anthology release, Final Stage: The Ultimate Science Fiction Anthology (Charterhouse, 1974; Penguin, 1975). He explains how Rinzler was demonized for being flippant about the genre and ruthlessly cutting up stories in the anthology without permission from the authors. As one might expect, this did not leave her with a lasting positive legacy, but Webster explores this with a clear-eyed and interesting perspective, avoiding a simplistic tarring of the editor and instead reminding one of the difficulties of being a female editor in a male-dominated field (and genre) in the 1970s, and how that might have informed her seemingly callous decisions.

Consequently, the book is at its best when Webster goes into more detail, going beyond indexing to actually give us a picture of the people involved behind the colorful covers of these anthologies, or distilling the essence of the stories in these volumes. For example, in the article “The Non (Final) Stage” (p.103) Webster paints an insightful and balanced portrait of the late Carol Rinzler, editor-in-chief of Charterhouse, and one of the guiding hands behind the botched anthology release, Final Stage: The Ultimate Science Fiction Anthology (Charterhouse, 1974; Penguin, 1975). He explains how Rinzler was demonized for being flippant about the genre and ruthlessly cutting up stories in the anthology without permission from the authors. As one might expect, this did not leave her with a lasting positive legacy, but Webster explores this with a clear-eyed and interesting perspective, avoiding a simplistic tarring of the editor and instead reminding one of the difficulties of being a female editor in a male-dominated field (and genre) in the 1970s, and how that might have informed her seemingly callous decisions.

There are other high points; including the articles “Three Nines Five,” the two-parter “WoWie, and Likewise ZoWie,” and “D-71: A (Sp)Ace Oddity,” in all of which Webster delves deeper with rewarding results. In these articles, Webster actually talks about the stories a bit, giving the reader some choice excerpts, instead of just a basic positive or negative appraisal. He also provides wonderful, illuminating snippets from personal interviews with editors and writers alike in his best pieces (it bears repeating that the man certainly did his research, and knows sf like a well-loved spouse).

His earlier articles suffer the most, with repetition (betraying their origins as a column, since he begins in the same way several times) and padding (using second-person voice to carry on a one-sided conversation that contributes little to the article). I also found Webster’s promise of providing a “historical context” to the anthologies disappointingly lacking most of the time, being limited to providing a rundown of major historical events in the years of publication, and not much else. To be sure, his grasp of sf publishing history is pitch-perfect, but he makes little effort to connect the history of the books with the history of the world they were born into.

This is a book for real fans of sf; that much is clear. But the question is, what kind of fan does it target? I’ll admit I don’t quite know. This isn’t exactly a friendly book for new readers of sf, despite being highly informative, since Webster often exhibits a subtle irritation towards those less acquainted with the genre he loves, as seen in an unseemly characterization of the common reader as “Joe Lunchpail.” There is an element of factual esoterica on display here that just didn’t engage me; it’s all interesting, but it didn’t bring these works or the times they were a product of alive in my head. I don’t see it being anything but dry reading for anyone who’s not already a fan of genre fiction. This is unfortunate, since a book this well researched and filled with fine recommendations of classic sf short fiction would greatly benefit those starting out with genre reading. But alas, Webster seems to ally himself only with collectors and seasoned sf bibliophiles who should already know what he’s talking about. This kind of exclusionism doesn’t befit sf/f at all, and it’s bound to encourage the Margaret Atwoods of the literary world who would characterize genre fiction as a silly little boys’ club.

This is a book for real fans of sf; that much is clear. But the question is, what kind of fan does it target? I’ll admit I don’t quite know. This isn’t exactly a friendly book for new readers of sf, despite being highly informative, since Webster often exhibits a subtle irritation towards those less acquainted with the genre he loves, as seen in an unseemly characterization of the common reader as “Joe Lunchpail.” There is an element of factual esoterica on display here that just didn’t engage me; it’s all interesting, but it didn’t bring these works or the times they were a product of alive in my head. I don’t see it being anything but dry reading for anyone who’s not already a fan of genre fiction. This is unfortunate, since a book this well researched and filled with fine recommendations of classic sf short fiction would greatly benefit those starting out with genre reading. But alas, Webster seems to ally himself only with collectors and seasoned sf bibliophiles who should already know what he’s talking about. This kind of exclusionism doesn’t befit sf/f at all, and it’s bound to encourage the Margaret Atwoods of the literary world who would characterize genre fiction as a silly little boys’ club.

To sum up; Anthopology 101 is a well-researched, extensive index compiled by an avid, knowledgeable fan of science-fiction. If that sounds like something you’d find useful, it’s worth buying. If you’re looking for an entertaining newbie-accessible text on sf anthologies, or a broader historical analysis of anthology fictions, I can’t say this is the best choice. Perhaps I’m being a young upstart by judging this book so, but if this venerable, malleable and infinitely powerful genre that we call science-fiction doesn’t have time for young upstarts, who’s it going to look to, to carry the torch in the future it so often represents?