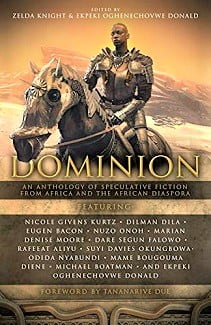

Dominion: An Anthology of Speculative Fiction from Africa

Dominion: An Anthology of Speculative Fiction from Africa

Edited by

Zelda Knight & Ekpeki Oghenechovwe Donald

(Aurelia Leo, August 2020, hc, 270 pp.)

“Trickin'” by Nicole Givens Kurtz

“Red Bati” by Dilman Dila

“A Maji Maji Chronicle” by Eugen Bacon (reprint, not reviewed)

“The Unclean” by Nuzo Onoh (reprint, not reviewed)

“A Mastery of German” by Marian Denise Moore

“Convergence in Chorus Architecture” by Dare Segun Falowo

“To Say Nothing of Lost Figurines” by Rafeeat Alivu

“Sleep Papa, Sleep” by Suyi Davies Okungbowa (reprint, not reviewed)

“The Satellite Charmer” by Mame Bougouma Diene

“Clanfall: Death of Kings” by Odida Nyabundi

“Thresher of Men” by Michael Boatman

“Ife-Iyoku, the Tale of Imadeyunuagbon” by Ekpeki Oghenechovwe Donald

Reviewed by Victoria Silverwolf

This anthology contains stories by African writers, as well as fiction by authors of African ancestry living elsewhere. Some of the tales take place in Africa, but others do not. Content relating to African cultures, or themes relevant to the experience of persons of African descent, appear in most of the pieces. In some, ethnicity plays only a minor part. Many of the stories freely combine science fiction and fantasy, making use of futuristic settings and mystical concepts in equal measure.

“Trickin'” by Nicole Givens Kurtz takes place in a post-apocalyptic setting. A supernatural being takes on human form on Hallowe’en, emerges from a cave, and journeys to the devastated city, in order to engage in a macabre version of Trick or Treat.

This gruesome tale is effectively chilling. The ruined metropolis provides an additional sense of menace to a well-written horror story, but is otherwise irrelevant to the plot.

The title character of “Red Bati” by Dilman Dila is a robot in the form of a dog, meant to serve as a companion for an elderly woman, now deceased. Placed in storage aboard a spaceship in a distant part of the solar system, it creates a simulated version of its dead mistress for company. As its batteries run out of power, it comes up with a plan for survival that will change everything for the other robots aboard the vessel.

The author manages to create an emotionally appealing story without living human characters. Although the reader is sure to sympathize with the robot’s struggle, the plot requires it to have abilities far beyond what one would expect for such a machine.

The protagonist of “A Mastery of German” by Marian Denise Moore works for a biotechnology company. She accepts an assignment to supervise a project that will allow memories to pass from one person to another, as long as there is some genetic similarity between them. The process has more profound consequences than expected.

Written in a realistic style, with fully developed characters, the story makes its speculative content believable. The author offers a thoughtful look at the way in which our memories make us who we are.

“Convergence in Chorus Architecture” by Dare Segun Falowo begins in an isolated community that emerges after a devastating war. A powerful storm strikes the land, and lightning strikes down two people, sending them into an extended period of deep sleep. When they wake, a gigantic vessel from another dimension draws one up into the sky. The other goes down into the Earth, on an odyssey that will allow him to save his people from the invader.

This brief synopsis gives only a hint of the extremely complex plot and background of the story. There are many striking images, and the author displays a vivid imagination. At times, the narrative is difficult to follow, and the ending, although intriguing, is obscure.

The main character in “To Say Nothing of Lost Figurines” by Rafeeat Alivu travels from one universe to another in order to recover a stolen object of great power. With the aid of a half-human inhabitant of the other universe, he recovers the item from hostile forces, but only by helping her in return.

This tongue-in-cheek adventure story has the feeling of a lighthearted sword-and-sorcery tale, with wit and trickery used in place of brawn and weapons. The characters are likeable, but they triumph over their enemies a little too easily to create any real suspense.

“The Satellite Charmer” by Mame Bougouma Diene takes place in a future Africa at a time when opposing Chinese forces both use beams from satellites to mine riches from the continent. The protagonist, struck by lightning as a child, has a strange mental connection with the satellites. The story follows him from youth to marriage and fatherhood. Because of his extramarital affairs, he loses wife and son, eventually winding up in a radioactive wasteland created by a satellite accident. Although he should be dead, his body nearly completely destroyed by the poisonous environment, he survives to join the satellites in a final, mystical vision.

The author manages the difficult task of blending near future science fiction with cosmic fantasy in a graceful way. The geopolitics of the setting are plausible, and the main character wins the reader’s empathy while remaining believably flawed. The style is sometimes plain and realistic, and sometimes poetic. Instead of clashing, these two contrasting techniques create narrative harmony.

“Clanfall: Death of Kings” by Odida Nyabundi follows the adventures of the last survivor of her clan after an attack by invaders, two warriors from different clans who find her in the desert, and a warrior from yet another clan whose assignment is to rescue the woman and kill the others. Although the setting is Kenya in the far future, the story has the feeling of violent space opera. It ends very suddenly, just when the reader is beginning to understand the complex background and politics underlying the plot.

“Thresher of Men” by Michael Boatman is a gore-drenched horror story in which a goddess of vengeance takes over the body of a human woman, in order to bring bloody justice to those who oppressed her people. The plot is episodic, involving both a modern police killing as well as a massacre that happened well over half a century ago.

Written with white-hot anger, the story powerfully conveys the rage of those who suffer injustice. The reader needs a strong stomach to endure its explicit violence, and may wonder if the punishments are sometimes worse than the crimes.

“Ife-Iyoku, the Tale of Imadeyunuagbon” by co-editor Ekpeki Oghenechovwe Donald takes place in a region of Africa that survived a third world war. Many of the inhabitants possess seemingly magical powers, which grow stronger as the population decreases. Contact with the outside world, made in a desperate attempt to avoid extinction, leads to a decimating battle with invaders. The main character is the only surviving woman of the disaster. She leaves the community, faces mutated outcasts, and undergoes a miraculous transformation.

The multifaceted plot deals not only with conflict between Africa and the rest of the world, but with a woman’s role in society. The African characters are varied and three-dimensional, but the outsiders are faceless soldiers who only kill or die in battle. (This may be excusable, since the main characters see them this way.) The special abilities of the inhabitants, and the way they grow extremely powerful as the population decreases, are difficult to accept, even as pure fantasy.

Victoria Silverwolf notes that this anthology also contains a poem by the author of “A Mastery of German.”