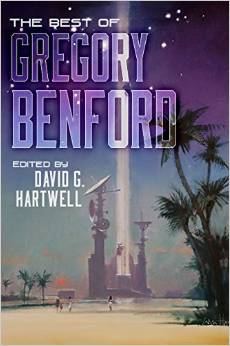

Edited by David G. Hartwell

(Subterranean Press, July 2015)

Reviewed by Bob Blough

Gregory Benford is a great science fiction author.

He is first of all a science fiction author. Notoriously one of the brand of SF authors who deals in the realities of science. I believe he calls it “playing with the net up.” His stories are full of actual scientific possibilities even if he is working in the far future. Nothing that does not fit into scientific possibility is considered for his stories. But the crucial second part of this equation is Gregory Benford is a science fiction author. He is a literate, well-read author who knows not only how to write a good sentence but also how to make a sentence sing. He writes hard SF with the pen of a poet. That is what makes his works so enduring and masterful.

As an example, in an early story, “In Alien Flesh” he tries to describe an encounter with an alien with the first sentences:

“-green surf lapping, chilling-

Reginri’s hand jerked convulsively on the sheet. His eyes were closed.

-silver coins gliding and turning in the speckled sky, eclipsing the sun-

The sheets were a clinging swamp. He twisted in their grip.

–a chiming song, tinkling cool rivulets washing his skin–

He opened his eyes.”

The sheer poetic power in those lines is mesmerizing to me. More follows as we learn Reginri’s story of why he has these dreams. He has literally crawled inside an immense alien. The story is fantastic in the genre sense with completely unknowable aliens. How this is described by Dr. Benford is nothing short of masterful.

In my opinion, Benford has three major types of stories (which overlap often). One is the story of scientists. This kind of story usually revolves around scientists just a step beyond what is being discussed at the time of the writing. “Exposures” is an excellent example (and personally my favorite short story of his). An astronomer is compiling various plates of film taken at the Palomar Observatory into an order that makes sense. In so doing the astronomer discovers the impending end of the world. His search for answers is mirrored in his personal life, one that includes his son’s teacher who has cancer. Benford creates a warmly human man who discovers that the world will be ending much too soon and measures it with a woman whose life is ending much too soon. There is no major action — no rallying the troops to change things. It is an elegiac story that ends in a church (even though the scientist is not a man of faith) where he and his son’s teacher experience the connectedness of all things.

So many of Benford’s early stories follow this pattern. In “Time’s Rub” the fact that some types of ancient pottery can be listened to as recordings is used to express the folly of humanity’s desire for remembrance. Or in the brilliant “Matter’s End” Benford posits the finding of the exact end of matter. The results, much like Clarke’s “The Nine Billion Names of God” create a very different reality. Other stories along these lines are “Bow Shock,” “A Desperate Calculus,” and “White Creatures.”

The second type of story Dr. Benford excels at are those of space and the alien. In these, he uses the science of our time to postulate what could be. His sense of poetry is most often applied in these stories. The already spoken of “In Alien Flesh” is an example. In “Redeemer,” he beautifully shows us a smaller craft coming alongside a gigantic ramscoop ship:

“The ramscoop vessel ahead was running hot. It was a long steel-gray cylinder, fluted fore and aft. The blue-white fusion fire came boiling out of its aft throat, pushing Redeemer along at a little below a tenth of light velocity. Nagara’s board buzzed. He cut in the mill mag system. The ship’s skin, visible outside through his small porthole, fluxed into its super-conducting state, gleaming like chrome. The readout winked and Nagara could see on the situation board his ship slipping like a silver fish through the webbing of magnetic field lines that protected Redeemer.”

Benford’s use of color and carefully chosen words makes this more than your average story about space. Another story, “Relativistic Effects,” is placed on a runaway generation starship (a la Tau Zero by Poul Anderson) using the main drive janitorial crew as his cast of characters. In it they observe great wonders wrought just by their ship’s passage:

“The ship itself, grown vast by relativistic effects, shone in the night skies of a billion worlds as a fiercely burning dot, emitting at impossible frequencies, slicing through kiloparsecs of space, with its glutinous magnetic throat, consuming.”

Others along these lines are: “Dark Sanctuary,” “World Vast, World Various,” and “A Dance to Strange Musics.”

Benford’s third type of story is of the “if this goes on…” variety. In “Freezeframe,” he tells a tongue-in-cheek story about work and family in the future. It is told, very cannily by Benford, in a monologue by a highly unpleasant man who feels entitlement to be his right. The story works so well because the voice is perfectly rendered. The man is unaware of his sense of privilege, his attitude towards others, especially women, and the fact that he, himself is a bore. In it he talks about the high tech needs of workers in the future and how that fast paced lifestyle may deal with the struggle of work vs. family. This one is very funny – and pointed, as well.

This type of story is well served by “Nobody Lives on Burton Street” (an idea that has, according to Dr. Benford’s afterword, been subtly used in riot control), “Doing Lennon” (which is probably his most famous piece of short fiction – and rightly so) and “A Life with a Semisent.”

Anther important factor to keep in mind while reading this collection is that Benford’s writing changed radically after 1989. David Hartwell mentions this in his introduction saying: “In the 1990s, by now an acknowledged master of hard science fiction, he became more playful in some works… That playful thread became more central after the turn of the millennium.”

I don’t know if playful is the word I would use. Benford’s works after 1989 are less passionate – not as full of his trademark beautiful writing. They are still excellent stories – based on hard SF concepts more along the lines of George O. Smith and Hal Clement, but what makes them singular creations of Gregory Benford is missing. Perhaps Dr. Benford gives us some idea of why this is in his story, “Mozart in Mirrorshades” from that cusp period. This is not an SF story at all, but an achingly realized account of Benford’s survival after an almost fatal burst appendix. In it he even mentions “White Creatures” (another story in this volume) by name saying he wrote it over ten years ago. But the line that struck me was:

“My fear of death was largely gone. It wasn’t any more a fabled place, but rather a dull zone beyond a gossamer-thin partition. Crossing that filmy divider would come in time but for me it no longer carried a gaudy, super-charged meaning. And for reasons I could not express a lot of things seemed less important now, little busynesses. People I knew were more vital to me and everything else seemed lesser – including writing. Maybe even physics.”

Perhaps this was a reason for the change in his later SF, perhaps not. So when you read these stories be aware that you will encounter two very different types of writing. Both are concerned with the same issues – scientists and their impact on earth, far future cosmological themes, and the alien – but there is a distinct dividing line which keeps the two separate. And while in the latter half of his career we are given excellent short fiction, the time travel (or, more truthfully, parallel universe) stories – “Mercies,” about killing past serial killers and “In the Dark Backward,” about visiting famous writers just before death – are good additions to that trope. Then there is the utter in-your-face horror of “A Desperate Calculus” in which the depredations of today’s world (overpopulation, destruction of ecologies, and rampant power in the hands of a moneyed few) are met by steel-hard truths. These and others are excellent works.

If you like your hard science fiction written in a plain, no-nonsense style, these latter stories will be for you. As for me, it is the intricate and beautiful stories of the early part of Benford’s career that beckon. In a story to commemorate the most poetic of SF writers – Roger Zelazny – Benford penned “Slow Symphonies of Mass and Time” in 1998. In it he tries to wed Zelazny’s beautiful prose with his own hard science fiction and while he nails some of the manner of Zelazny’s writing with admirable precision, he just doesn’t quite capture the elegant beauty that only Zelazny could envision – but then who could? But, I believe that Benford, in his early stories, had been doing that all along – marrying elegant prose with the science and in so doing became the poet laureate of hard science fiction.