“That Matter at Hand”

“Retro-Virus”

“Pun Gazing”

“Smooth Maneuver”

“Bidding the Walrus”

“Euphemism Skin”

“Pidgin”

In his introduction to this collection, Mark W. Tiedemann says that science fiction writers love to evoke the Ooh Factor. I agree. The aims of literature are about as varied as the actions of the human beings they mirror, but one thing that unites most science fiction writers is our fascination with nifty ideas.

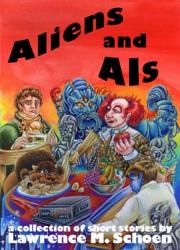

Lawrence M. Schoen’s fiction is chock-full of nifty ideas. His futuristic computers alone are fascinating, and he designs really cool aliens, then turns them loose to interact with everyday humans—ordinary people encountering the extraordinary—one of literature’s favorite tropes.

Most of the stories here feature a human dealing with one or more aliens. In “Pidgin,” language is the problem—it’s a short, funny story told in a single scene. “Euphemism Skin” is also an extended scene—a negotiation with an alien confederation who may or may not grant us humans starship capabilities . . . if only their prejudices against our more disgusting traits can be overcome. (The disgusting traits are not the obvious ones.) Like the above, “Smooth Maneuver” is a single character observing aliens, thinking out the consequences of a single action on the part of aliens in a public forum.

“Bidding the Walrus” is a slightly more complex story, with two humans. The narrator is Walrus, who runs a small business designing modular robots in a space station where A.I.’s are strictly forbidden. He has a single worker, Weird Tommy, who has a lot of emotional and mental problems, but who works hard, and about whom the narrator cares. I liked this story best, I think, for its human interaction mixed with nifty ideas—these arising from a gift (?) an alien gave Walrus in thanks for a job well done.

The opening story also has two humans—the protagonist, a wealthy, successful business-man who was once a stage hypnotist and his slightly shady card-shark sidekick, Left-John Mocker, who are up against an alien gambler who wants an all-or-nothing game over a business deal. A telepathic alien. Playing a game, called Matter, which has no rules. I could tell by little signs in the story where it was going, but I wanted to see how it would get there.

It’s a fun story. These are all fun stories—very short, with perhaps one, or at the most two, plot complications. Readers who demand more complexity to their characters might wish for more depth, for change, for interaction outside of the central idea—readers whose tastes run to sfnal ideas and imaginative aliens will be right at home.

The remaining two stories read differently to me. I hesitate to proclaim that they "aren’t stories"—the author clearly intended them as stories, and they were published as stories. Who’s to say what a story really is, especially these days, when Snarkoblog is raving about Author X who cannot write a story to save zir life—at the very same moment that Bloggodoom is commending Author X for lethal kewlth in slipstream (or flash) fiction?

Instead I will say that “Retro-Virus” functioned less successfully for me as a story than as a possible chapter one for a smashing novel. Here’s Jonathan, whose corporate A.I., Marcie, has somehow sucked up a virus. The story opens with an involving scene with a weary Jonathan trying to solve the viral problem while interacting with Marcie, who is experiencing the data craziness as physical symptoms. When Jonathan vanishes from the scene and we’re left with Marcie the ideas take over—with a breathtaking concept that is told us, not shown, in one quick narrative punch. The questions I was left with overwhelmed the rest of the story—I don’t think I’ve ever wished harder for Chrestomanci to drop by and shift me to the next universe over, one in which there would be five hundred pages following that opening chapter.

The next one, “Pun Gazing,” read to me like the outline of another fabulous novel. It opens with an intriguing graph:

“Imagine autumn. Smell the tang in the air; someone is burning leaves the way they used to all over New England. . . . Wriggle your toes in your socks and ponder for a moment how it must feel to your shoes. Do all these things and ask yourself if any of it constitutes the human experience. No, wait, don’t bother; it’s a rhetorical question. Here’s one that isn’t: ask yourself what it would take to build an A.I. that could do these things . . “

It was just stunning in its breadth of ideas. Mentioned was only one character, Burt, who wonders about such things. We’re only given his background—we never actually see him in a scene, he has no conflict or change or even direction. This story, as presented, is pure idea, starting from Burt’s work in college (designing a expert system named Parry that could generate multi-lingual puns) and I believe if it were matched with characters, conflict, scenes to equal the potential scope, Schoen could give Neal Stephenson a run for his money.

Publisher: Eggplant Literary Productions

E-Book Price: $3.50

ISBN: 1932207414