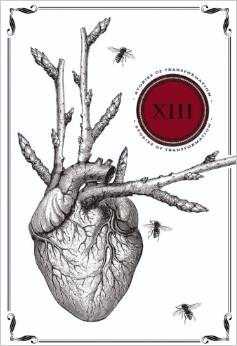

XIII: Stories of Transformation

XIII: Stories of Transformation

edited byMark Teppo

(Underland Press, March 2015)

Reviewed by Nicky Magas

Opening the anthology is Adrienne J. Odasso’s “Skin and Paper,” which sets a more or less accurate tone for the stories that come after it. Dark, playful and somewhat sinister, this short welcome to the book is chilling in its chaos, inviting in its casting off of sanity, and will stand up the hairs on your neck like a disembodied voice in the dark.

Tais Teng’s “With a Musket and a Ducat The Dutch Trading Company in Nineteen Sketches, Paintings, and Luminos” is a steampunk alternative history told in nineteen vignettes. It follows the life of Shan-Pier Memling from his birth to a poor Dutch family until his death and then on to his resurrection. As a boy Shan-Pier had a head full of adventure and curiosity which ultimately lands him in the service of The Dutch Trading Company. There he works as a sailor until he gets sick of the job, steals a great deal of wealth and returns to his family in the Netherlands. Pier is no stranger to theft before this point, and doesn’t give up his criminal ways when he and his sister Frieda set off on their own to bring the Company down via the sale of trade secrets to rival companies. But a man can only run on lies and shaky alliances for so long, and The Dutch Trading Company is not known for mercy. When they finally catch up with Pier, past loyalties and even blood relations are bartered against his life. For a man with a history as black as Pier’s, the decisions that follow seem like obvious ones.

“With a Musket and a Ducat” starts strong and had me genuinely interested in the story up until Shan-Pier returns to the Netherlands. From there it feels as though the story loses its roots as an alternate history and spins off on its own as SF without many ground rules for the reader to acclimate to. Technology rapidly advances between scenes, the characters become increasingly melodramatic, and dialogue serves as clunky exposition to inform the reader what they have missed in between each of the short scenes. Any serious tone the story originally has is lost in cultural caricatures. Additionally, the great leaps in medical advancement rob the story of any sense of danger it could have had. Even when Pier is eventually captured he is sentenced only to ninety years of hard labor, a punishment which seems ridiculously light given the fact that the reader is told at the beginning of the story that simply stealing some money from his family is enough to earn him the removal of body parts. Ultimately the characters in “With a Musket and a Ducat” are secondary to the steampunk artifacts which are showcased within it, leaving the reader with little to be invested in, once the plot finally starts moving.

Selma is voraciously hungry in Fiona Moore’s “Selma Eats.” She doesn’t know what or possibly who she is, or why she’s so hungry, but the books in the bookstore where she lives and disperses herself at night is full of delicious books to eat. Maria works at the bookstore and keeps Selma company. She gives Selma delicious old, used books to eat, instead of the new ones in the store. Selma quite likes Maria and her ideas and her books, but something is causing her friend to have dark red thoughts. The man who comes by the bookstore scares Maria, and Selma can’t figure out why. If one thing has ever been clear to Selma, though, it’s that the dark red tasting man has to go, for the sake of her friend, and for Selma’s own curiosity.

“Selma Eats” is told in a delightful first person narration that makes the reader think of Selma as a young child, ‘hungry’ for knowledge, bursting with curiosity and reaching for the simplest, most obvious solutions. While this is obviously not the case the further the story goes along, this initial impression keeps the reader endeared to Selma, even when we can see where the plot is inevitably going. Both innocent and chilling, “Selma Eats” is the sort of horror story which makes the reader cheer for the monster, and perhaps to wish that the story would continue for a few more pages

A shadowy doppelganger haunts the protagonist of “Oh, How the Ghost of You Clings” by Richard Bowes. Near the end of his life, it seems that there’s nothing left for the old protagonist to do but ruminate on the past. Fortunately (or unfortunately, however you look at things) he has a Shadow who has appeared at various points in his life, mucking about, making a mess or just whispering in his ear. While the Shadow has always seemed like an ill omen, when he looks back at his life, he can’t help but wonder if maybe this strange entity hasn’t been sent to him for a good purpose.

While reading “Oh, How the Ghost of You Clings” I found myself waiting for a punch line that never came. There is a lot of lead up in the story, but unfortunately it doesn’t go anywhere. The events which are both active in the present and remembered in the past don’t appear to be connected at all and if the final realization that the Shadow was actually beneficial in the protagonist’s life is the point of the story, then the whole thing fails to impress. Additionally, I had a hard time visualizing the protagonist (and his Shadow) as a seventy year-old man when the first person voice sounds several decades younger. This element alone was enough to keep me outside of the story, and perhaps hindered a deeper understanding of it.

A researcher goes to the dry bones of Earth to return to her roots in “You Can Go Anywhere” by Jennifer Geisbrecht. Why she’s chosen to accompany this small team to the planet so noxious it requires her to wear a lead hazmat suit is anyone’s guess. After all, having graduated with honors, the solar system and all its possibilities are wide open to her. But Earth is where she wants to go, and almost as soon as she’s touched down she parts with her team to explore on her own. What she finds are the ruins of long dead civilizations, an inhospitable environment, a sense of peace and… something else. It is both alien and familiar, frightening and comforting. And it wants to talk.

Mixing science fiction and theology, Geisbrecht creates a story that questions the origins and destination of humanity. She explores the seduction of oblivion—or perhaps a desire to return to the inevitable, primal elements that are the component parts of our animal bodies, complete with the animal instinct to survive. While the concept of God (or a god-like being) as an alien isn’t new to science fiction, Geisbrecht chooses to focus more on the singular interaction between human and alien, instead of between the alien and humanity as a whole. The result is a wholly intimate experience in which the reader feels keenly the struggle of the protagonist to identify herself and her purpose to a higher being. While the split column, simultaneous conversation between them can be at times difficult to follow, it adds to the overall feeling of the story and allows readers a sense of the protagonist’s own confusion during the encounter

Evil genius and secret agent go together like pie and ice cream, and no one knows this better than David Tallerman’s Eponymous in “Twilight for the Nightingale.” For years Eponymous has battled with Agent Nightingale and not once has he ever been disappointed. Nightingale is cunning, intelligent, strong and determined, and nothing brings pleasure to Eponymous’s life quite like knowing that Nightingale is hot on his trail. So when Eponymous sets the mother of all elaborate puzzles for Nightingale to work through, he has no doubt it will be a walk in the park for the crafty agent. A doomsday device on a countdown only sweetens the suspense. Nightingale will come. He must come. Life just isn’t worth living without him.

Tallerman works magic with pacing in “Twilight for the Nightingale.” The plot of this relatively short story, as well as all the juicy little details that make it such a pleasure to read unfolds like a slow blooming flower, one petal at a time. The reader is able to savor each element of the story this way, rising with delight and horror to the climax and the chillingly simple ending. While the prose makes the story tongue in cheek, the villain/agent dynamic isn’t what’s important in this story so much as the relationship these two share. A little touch of absurdity mixed with the deeper emotions and connections here makes “Twilight for the Nightingale” very easily palatable.

Lyn McConchie writes a tale both mournful and triumphant in “The Thirteenth Ewe.” As a Keeper of her family’s sheep, Shani is expected to make the yearly drive into the hills and back again with her twelve ewes. She returns twice a year: once in the winter to pen the flock safely, and once in the summer to sell her lambs. It is all done for the Goddess, and for the love of tradition and their animals. But one day a factory is built in their village, the first nail in the coffin for the old ways. Soon, Keepers are giving up their flocks to work in the factory, the village becomes a city and the sheep are squeezed out of the community bit by bit until only Shani and her flock remain. When her ambitious brother begins to see Shani and her sheep as an obstacle between him and a mayoral position, he does everything in his power to rid himself of all of them. But Shani has one more trick up her sleeve: the Goddess who has always protected the village and the sheep. But has she abandoned Shani the way the village has abandoned the Goddess? Truly, this is Shani’s last option.

This is a sweet story written in sweet prose, and if you’re expecting a revenge plot at the end, you’ll be disappointed. Perhaps that was the only thing that fell flat with me as I read the story. The conflict between Shani and her brother seems to blow away at the end, leaving the reader feeling a bit unsatisfied. Everything else about this charming story is a lovely delight to read however, and the reconciliation between the old and the new is enough to redeem the loss of satisfaction from the conclusion of the final conflict

Make sure you have a box of tissues handy before reading Liz Argall’s “Augustus Clementine.” The unusual hero of this story, Augustus, is a roller skate for hire at a roller rink. He’s not the prettiest or the newest roller skate, but he works well enough, and when he gets banged up or broken, he’s always repaired. Until one day the break is too great and Augustus is stripped of his parts and thrown out, certain this is to be the last of him. But somehow it isn’t. Augustus’s journey is only beginning, and it will take him to many places and give him many experiences until at last, at the very last, his usefulness is ended.

I have to admit, this story had me in tears before the end. Argall tugs at all the right heartstrings to produce a beautiful medley of emotions in the reader as she takes us with Augustus on his many adventures. From roller skate to prosthetic limb to memorial artwork, Augustus’s story is touching and tragic and redeeming all in one. With every rising hope for a new happy ending, there is instead a new transformation until finally Augustus is put to rest and the reader is left to pick up the pieces.

In Julie C. Day’s magical realism story, “Pretty Little Boxes” Celia, a Sadness Carrier, goes to extreme lengths to try to instill some empathy in her recently cold husband. After one of her sadness boxes causes a client to kill himself, all Celia wants is to get out of the business. Her husband Barry, on the other hand, thinks of nothing but the loss of income that this permanent vacation brings to their home. When Celia finds an all too conveniently placed receipt that shows just how much Barry values money over her happiness, the only option left to Celia is to make her own box, and fill it with all the sadness she wishes her husband would feel.

I get the impression that this story is trying to say a lot about many different things. Between the time jumps and the vague magical structure of the world, however, it’s hard to unravel the allegory here. The reader picks up on hints of abusive, manipulative relationships; commentary on depression and suicide; and even some commentary on the nature of sustained emotional trauma. Take “Pretty Little Boxes” just at face value, though, and the reader has a story of love, betrayal and hope—and that aside from any other meaning might be enough to make it an enjoyable read.

Grá Linnaea’s “Two Will Walk With You” is an historical fantasy in which Ayu is on the run from the wrath of the Christian missionaries in 1589 Japan. After killing her master, the seventeen year-old who had been forcefully indoctrinated into the church, flees for her life. She knows the punishment for murder is death at the hands of the Socius, the demon conjured for the sole purpose of eliminating its target. With what magic she has learned in her six years as an acolyte, Ayu manages to slip past the protection wards around her former prison, but runs directly into the demon sent to kill her. Wanting a bit of fun, however, the demon lets her go, to continue the game of cat and mouse until it grows bored. With this limited breath of freedom, Ayu runs to the aid of the first man she meets on the road, Hageatama. They strike an uneasy friendship at first, but before long are close traveling companions as they attempt to outrun and outwit the demon relentlessly stalking Ayu. But how long can Ayu run from that which is destined to destroy her? When the opportunity to settle in a quiet mountain town becomes too tempting for Ayu to pass up, can she put friendship, love and community at risk for her own happiness?

With a lengthy set-up, superfluous Japanese words and a timeline stretching over sixty years, the scope of “Two Will Walk With You” is too large to fit within even the long length of this story. Spanning nearly the entirety of Ayu’s life, there is little time for the reader to grasp important events before being whisked forward in time again. The story picks up its pace after Ayu and Hageatama reach Ojiya, and runs the risk of leaving the reader behind in short vignettes of rapidly passing time. This is particularly upsetting, as I feel the heart of the story is supposed to be in the Ojiya setting, however much of the detail and word count is put into the world building and backstory of the beginning. This results in the second half of the story feeling rushed and underdeveloped. The introduction of Megumi as the instant love interest, for example, would be onerous if the reader doesn’t pick up on the hints that she is, in fact, the Socius in disguise. In the end, the events in “Two Will Walk With You” which feel the least important get the most words, while the important events are fast-forwarded to the ending that the reader already knows is coming.

Worth and Anchor are the last angels left guarding a dilapidated citadel after the Fall in Christie Yant’s “Eidolon.” Ever since that fateful day when Worth decided not to take a stand against the oppression of heaven, he has harbored an uncomfortable crisis of identity. After all of their compatriots had fallen, only Worth and Anchor remained, the two tacitly rebellious angels who chose not to fight. Now, they do little with their time but wander around the Citadel. Occasionally, a spark of a soul flares up from the earth below as the humans dream, but they always diminish before they actually reach Worth’s vantage point. That is, until one day a soul manages to make it all the way up. Martin, as he is called, makes his way to Worth’s metaphysical plane in a dream and, seeing the crumbling Citadel, feels an instant attraction to it. The trouble is, the road had been destroyed in the Fall, and no one can get across without flying. When Worth refuses Martin his wings, Martin leaves, vowing to return. To Worth’s surprise, he does so, bringing within him all manner of building supplies to make a bridge across the gap. Worth can’t understand Martin’s strange fascination with the Citadel, nor his own growing understanding of himself. Martin, however, is a fascinating creature, and the more Worth watches him tirelessly work, the more he unglues himself from the memory of the Fall, and the subconscious guilt of his desertion.

While “Eidolon” feels a bit obscure, as though missing something vital from the mythos of heaven, it nonetheless is a touching and charming story in its subtle emptiness. There’s a peace in the setting, the characters and the prose itself that has a calming effect on the reader, and makes the whole story endearing. Worth’s unspoken fears are palpable throughout the story, and the repression of his self that stems from those fears is easily relatable to the reader. Martin, on the other hand, is Worth’s perfect foil. He’s fearlessly determined to reach his goal, no matter the cost or the danger. It is through Martin that Worth is finally able to come to terms with his past, and do what he should have done years before.

In a chilling look at the future of triage care, Rik Hoskin gives us a hospital where doctors are forced to work fifteen hour shifts…on patients from the future, in “Slow Shift.” Jane is tired. She’s been working around the clock on present-time patients and future patients both. But with the regulator—that bothersome piece of technology that allows hospital management to maximize the precious downtime of the ER by filling it with patients from the future—on standby, Jayne is able to catch a few minutes to do some low stress paperwork. Unfortunately, management catches her in the act and after a warning, it’s back to the non-stop stress of an ER doctor’s life. The regulator has certainly changed how emergency rooms are scheduled, but the downside is that even though a patient comes from the future, that future is unalterable, no matter how grave—or fatal—the injury may be. Sometimes, seeing into the grisly future is an ability far too weighty to handle.

With ER accurate setting details and characters with believable skillsets and habits, Hoskin puts the reader directly into what feels like a real emergency room. The stress and constant activity that come from being an emergency doctor is very real in every line of the story, even before the characters’ workloads are increased by the inclusion of patients from the future. Anyone who has ever been in an emergency room will instantly recognize—and sympathize—with the characters and events of this story that is so realistic, it almost doesn’t need the science fiction.

In a tree in a forest sits a witch waiting for her next meal in “The Math (A Fairy Tale)” by Marc Levinthal. When they come, they come for her feast and that’s when her minions catch them, carve them up and feed them to her ravenous hunger. Occasionally she wakes from her fantasy dream, but the world is still broken, still dead and still gripped in Dream addiction. So she returns to her tree and continues to eat those who find her. But the meals are growing fewer and far between, and every new visitor could be her last.

The twisted elements of “The Math” held me from the start, and the introduction of the science fiction aspect of the narrative only made the whole thing sweeter. What I especially loved is the fairy tale-esque prose that dominates most of the story, giving it a charming, surreal feeling that compliments the entire thing. Unfortunately, the ending is clumsily executed, and breaks the magic the story previously maintained. The point of view switch and the tin-eared, as-you-know-Bob dialogue between the remaining two characters makes the ending feel unpolished compared to the rest of the story, and since not much is added in this epilogue aside from a final image at the end, perhaps “The Math” could have done without it.

Farmer’s almanacs are nothing more than superstitions and old wives stories. Nobody relies on them anymore in an age of instant digital information. John in Richard Thomas’s “Chrysalis” sure hopes that’s the case, anyway. He lacks the experience of some of the more entrenched famers of the area. After all, he doesn’t even farm his own land, but rents it out to locals for private use. He’s read The Old Farmer’s Almanac casually, and when he starts seeing the ominous signs of a seriously harsh winter to come, John starts to wonder if there isn’t some truth to the outdated books. But it’s the Christmas season and money is scarce. Can John afford to put all his faith and cash in the warnings of the almanac, at the expense of his family’s happiness and possibly his own marriage?

“Chrysalis” is full of great sensory details that put the reader right there on the farm with John, experiencing every aspect of the autumn and winter leading up to the big storm. Perhaps because of this attention to detail in the setting, the characters and their relationships to one another feel a bit watered down. Pieces of John’s past and his interactions with his son in particular seem like they will play a key role in the story, but ultimately don’t go anywhere, other than adding tacit tension between he and his wife at the end. The story is ultimately enjoyable, however, as the reader partakes in John’s obsession, experiencing an oddly real thrill of the will it/won’t it anticipation of the storm predicted by the almanac.

In a chilling dystopian tale, Gregory L. Norris gives readers two men grasping for happiness and a ray of light where there is none. When the Treasury assigns Boke the house with the cobalt blue lamp on Maple Street, a house he knows well both by its signature lighting and the two men who previously occupied it, Boke has reservations. He remembers the house, after all, and its history before—and after—the purge. But Boke has little choice other than to be grateful for the housing, and when the Treasury assigns him a housemate, Boke has to admit, another person around does ease the loneliness. The ghosts of the past however, won’t be displaced. Boke and his new roommate Shotton are both dogged by the sounds of the lives left behind by the two men who lived in the Maple Street house before them. Real, imagined, and super natural—whatever they are, they draw Boke and Shotton inevitably closer, huddling together for warmth and light, like all the other Treasury worker families.

The gloom and loneliness are thick in this relatively short story. Very few of the key events are actually on the page, however the descriptions used and the subtle allusions to the horrors of the past make the reader grateful to not be privy to those details. Little is said about either Boke or Shotton, but within the context of the story it works. Both men are guarded, and have seen and lived through too much to be open with each other, the reader, or even themselves. The less is said the better. It is understood by the reader that there is no past and no future. Whatever happens in the present is all that is real, and what happiness can be found in this moment ought to be grasped and held onto.

“Feed Me the Bones of Our Saints” by Alex Dally MacFarlane puts the reader in a desert scorched by two suns, among a people starved of food and culture, robbed of their cities and their legitimacy by their warring neighbors. Jiresh and Iskree are two among the last remaining members of the desert tribe of woman and fox partnerships that once dominated the region. They have been chosen by their people for their bravery to return to the cities that were once theirs and retrieve the bones of their saints, which were entombed fifty years earlier. The journey is not an easy one. Between the sun and the barren desert, they only barely make it to the resting place, only to find the bones of their saints gone, stolen by their greedy enemies. All they have left is the possibility that the bones were taken to a museum in Caa, and there, Jiresh and Iskree scribe their final fate.

Beautifully obscure in its prose, “Feed Me the Bones of Our Saints” unfolds slowly, showing the readers a single side of the narrative history between Jiresh’s people and that of her enemies. While the reader knows that the story isn’t going to end well, it gives the reader a taste of blood and victory and revenge before dying off with the last coals. There is obviously so much more here than is said, leaving the reader with a desire to dig further under the sand to uncover every little bit of history buried under the dunes.

In “Creezum Zuum” by Juli Mallett an unknown narrator—perhaps a character, perhaps the artist’s own inner critic—addresses an unknown writer about his or her deepest fears of the self. It gets to the heart of art as an expression of, and connection to, the soul. We are changing who we are every moment of every day, with no idea of what will come of the change, only the knowledge that we are leaving innumerable versions of ourselves behind. In this short, self-referencing story, the writer is presumably attempting to capture the dual trauma and release of change in something trendy and cyberpunk, to write about the blind faith of accepting change as inevitable, and finding stability in the permanence of impermanence.

Among the ever growing—and rotting—bones of the towers in Fran Wilde’s “A Moment of Gravity, Circumscribed,” lives Djohnn, his father, his brothers and Raeda, the girl Djohnn’s father looks after until her uncle gets back on his feet. Djohnn is impossibly clumsy and impossibly curious, a disastrous combination when he breaks his father’s prized ticker. Faced with no other alternative, he bargains with Raeda to take him to the moldering bones of Lith, a long destroyed tower below the clouds, where he hopes to find a treasure at least equal to the one he destroyed. But though they try to make their decent in secret, they soon discover that they are not alone under the clouds. Someone else has followed them into the dark, lonely hollow, where no one goes looking for the bones of the dead.

Lovely prose and subtle descriptions combine to form a story that is entertaining as well as fast paced in “A Moment of Gravity.” The world unfolds around the reader while the characters fall through it, opening new sights and themes to the reader’s view, bit by bit. The story doesn’t take many risks, and more or less goes where the reader expects it to, but this gives the reader more time to enjoy the sights and take in the ambiance throughout the journey.

“We All Look Like Harrie” by Andrew Penn Romine is a story of the frantic life of androgynous night clubbers, dancing like candle flames in a dystopian world of drugs and organ thieves. Harrie is dance floor royalty. Everyone wants to be a part of Harrie’s orbit and mimic Harrie’s flare in cheap imitation knock offs. But Harrie has no favorites, and fame at Harrie’s side is short lived. While the dancers sicken and starve themselves for a moment of glory in the clubs, the dark world outside extinguishes them one by one, and no one, not even Harrie, is safe from that reality.

Romine gives this story some fantastic imagery that throbs with the beat of the music and the dancer’s feet. The reader can’t help but breathe the sweaty, drugged frenzy in the air as the characters swirl around each other in an unreal galaxy of fashion and music. The temporary nature of their world, however, is sharply underlined, both in the impermanence of the fame of the dancers, and in their very lives picked off one by one in the dirty streets for their glittering organs. These images side by side paint a hauntingly beautiful picture for the whole story.

A.C. Wise’s “Letters to a Body on the Cusp of Drowning” is really several stories stitched into the skin of one overarching theme. Kit wants to be a sailor more than anything else. The only problem is she’s a woman. So Kit practices at being a man, binds her breasts, cuts her hair, learns to drink and cuss and ultimately runs away and joins the crew of an outgoing ship. But when the crew pulls a beautiful, enchanting sea-witch out of the waves, Kit is given the chance to change herself at will. The price? Only the sea knows.

Told in bulk in a series of letters to a future version of Kit, confused by who she is and terrified of the sea, “Letters to a Body on the Cusp of Drowning” gives the narratives of a mermaid, a selkie and a goddess who all gave something of themselves in exchange for the dream of transformation. They, like Kit, all got their heart’s wishes, but the ocean keeps tabs, and eventually, like Kit, they all must return to the waves. The letters in part explain the nature of this give and take relationship that Kit has forgotten, and in part reassure her that the drowning part, the part she fears the most, is only a small part in the transformation as a whole.

Some people have normal problems: addiction, depression, instability. For the members of Damned Anonymous of George Cotronis’s “Blackbird Lullaby,” problems are a bit more visceral and the demons a bit more literal. Cravings for human hearts, tears of blood, and animals picking living flesh directly off of bones is a normal day for the unwillingly damned, but at their small support group they find comfort and compassion among their fellow damned, and perhaps even love.

Standing the zombie genre on its head, Cotronis gives the classic narrative a more sympathetic element. No one in the Damned Anonymous group asks to be the way they are, it just happens, and they carry on with their lives as normally as they are able, knowing that the inevitable transformation into some unknown, monstrous being is somewhere on the horizon. The first person narrative aids the empathetic feeling throughout the story, and gives readers a fresh perspective on what it means to be a monster, and a human being.

Franklin wakes one day to discover his consciousness is not in his head anymore, in “Digital” by Daryl Gregory. Ever since his stroke and subsequent tumble down the stairs, Franklin has been processing the world through his left index finger. As strange as it is intellectually, to Franklin, it feels like the most natural thing in the world. His wife Judith is less than impressed, however, and can’t understand Franklin’s new point of view. It takes a kind physiotherapist named Olivia to allow Franklin to be open and honest about his new life. Surprisingly, Olivia not only believes him, but accepts him as well. Soon, everything in Franklin’s world is hand centric, and though science can’t account for his shift, his consciousness isn’t finished with its travels yet.

With clever prose and a cute narrative, Daryl Gregory engineers a lovely tale of philosophical science fiction. The idea of where the self is homed has been a topic of debate among scholars for thousands of years, but though everything from the brain to the heart to the stomach has been proposed, “Digital” might be the only place in which an index finger is said to be the home of the self. Touched with humor and foreshadowing, “Digital” is a vastly entertaining read for anyone with a curiosity for where ‘me’ is.

In “Why Ulu Left the Bladescliff” by Amanda C. Davis, Ulu has had her heart broken by Cleaver and now there’s no going back. Her neighbors have watched her cleaning her house, preparing for Cleaver’s return all day, but he comes to her not with affection, but with the news that he’s leaving to be with Butcher. All that’s left for Ulu now is escape, and with a pull of a brass lever, her house uproots itself and rolls down the cliff. Down to where Ulu doesn’t know, but she hopes it’s a place of happiness and light and that’s good enough.

The prose in “Why Ulu Left the Bladescliff” can at times be a bit confusing. The line between what is real and what is imaginary is blurred throughout the story, but once the reader gets a sense of the rhythm and tone of the narrative, it’s easier to distinguish events from description. Somewhat lacking in any emotion other than numbness, readers empathize with Ulu not from what is on the page, but through connection with similar experiences, similar hopes born of pain, and similar needs to leave the entirety of a ruined life behind in search of the next patch of sunlight.

Jetse de Vries’s “Follow Me Through Anarchy” can be summed up in the title. Alex is an autistic, presumably, so obsessed with androgyny, so focused on communication and interaction that he/she has become both, all and nothing of everything. Alex has lost her/his ability to remain in one time, place or state, and through his/her interview with the strangely insightful, frighteningly intelligent Tanaka, Alex is whipped in and out of reality, philosophy and physics, anchored to everything and nothing, with a tenuous grip on what is real and what isn’t.

Unfortunately, while “Follow Me Through Anarchy” does pull itself together in the last couple pages in an attempt to make some sense, much of the beginning of the story truly is anarchy. A cacophony of information barely touched upon before the next topic is introduced, it becomes hard for the reader to tell what is important and what is not. If it is meant as an introduction into the thought process of an autistic individual, then this jumbled, chaotic presentation of scenes makes more sense. If not, I’m not sure what, exactly, the story is about; de Vries asks the reader to hold too many cards throughout this lengthy story and by the end, half of them have tumbled to the ground.

The ghosts of two dead twins haunt the inn of their family in Cat Rambo’s “The Ghost Eater.” Dr. Fantomas is a ghost-handler, and along with his assistant Charlotte, they wander the world, extracting ghosts from where they are causing the living stress and harm. On the surface, the ghosts of Ellie and Kim are like any other poltergeist Dr. Fantomas has dealt with, but despite everyone’s insistence that Kim is the one responsible for the unwelcomed happenings in the inn, Fantomas has his reservations. There is a mystery to be unraveled before the exorcism can take place. Were the girls’ deaths really an accident, and how deep does sibling rivalry run in matters of the heart?

Written in a gothic style, “The Ghost Eater” is dark, mysterious and emotional. Dr. Fantomas remains an apathetic character until the final scene, which serves to highlight the turmoil that happens around him as a result of the ghostly activity. I was most surprised by Charlotte, however, as even given hints in the beginning, her character went to places I did not expect, which is always a plus.

The world and all its soldiers and wars have ended in “The Soldier Who Swung on the End of a Thread” by M. David Blake. Someone pushed the button, and the destruction that the doomsday weapon brought was catastrophic enough to decimate all enemies on both sides, active and covert. Ossuera, one such soldier, has awoken to an enemy who offers to patch her up with parasitic thread technology. As he heals her, he fills her in on the dying days of the war, of how he, the leader of his side pushed the button that ended it all. It wasn’t how he intended it, and he gives her a choice. Pursue him now, kill him in the chase and be the hero the world needs, or fail and he finishes what he started. The choice is not much of a choice for Ossuera—a good soldier—and she pursues her enemy through the villages and lives he destroys, all the way to the weapon that will end all of humanity.

Admittedly it’s a little hard to follow this story at the beginning, as no specific identifiers are really used to help the reader understand the overall history of the people or the conflict that set the current scene. This is all in keeping with the general tone of the story, and its commentary on war and doomsday in general. The middle lags a bit as Ossuera pursues her foe, and by the end, I wasn’t entirely sure if the chief antagonist was the old man or the threads healing her body. Still, the writing is solid, and the overall setting so near to what the world is like presently that the story produces chills whether it is understood as it was intended or not.

“Rabbit, Cat, Girl” by Rebecca Kuder is a wandering tale about a girl, a fire, an evil felt rabbit, and the ghost of a cat. The girl, who lives alone with an angry father after her mother left the family, takes comfort in her cats. She has had many cats, but there’s one cat in particular, a cat that she must have sleeping beside her each night, even in the heat of summer. Even after the cat has died. And it’s a good thing too, because that wicked toy bunny has insidious thoughts. How else can you account for it being the one thing to survive the house fire with not a single smear of soot on its white fluff?

I liked the disjointed, tangential feeling of this story and the way it meanders from topic to topic, getting lost down the rabbit hole it references. Much of the story demands reader inference to understand, and it definitely isn’t a story that can be read with half a brain. If there is one thing about it that bothered me it was not knowing who—or what—the narrator is. I got the impression that this was going to be revealed at the end (or perhaps that was just my expectation) but it is never mentioned. The narrator’s identity feels like a key to unlocking a secret hidden meaning in the story, and without it I keep scouring each line for more clues that aren’t readily forthcoming.

In “The Thirteenth Goddess” by Claude Lalumière, something strange is happening in the city of Venera, something stranger than the river bleeding every month. Body parts are washing up on the river’s banks, and the city itself seems to be alive. Detective-Inspector Dovelander is dispatched to Venera at the request of the Church of the Earth Mother to investigate the murders but to his Catholic soul, the city is a confusing mess of obscene imagery and rituals. How is he expected to untangle the mysteries of the city when he can barely understand its heart? A heart that seems to pulse and beat and pump its own blood into the river every month.

“The Thirteenth Goddess” took a bit of warming up to, and because of that I’m glad that this one was a little longer. Filled with blunt, carnal imagery and a moist, pulsing energy, once the reader is made comfortable with the setting, the story unfolds in a series of short, engaging chapters with unique characters the reader wants to follow. While the mystery at the beginning seems to be its focus, “The Thirteenth Goddess” sheds this perception near the end and is resurrected into a whole new tale of mythology and rebirth. While I enjoyed this aspect of the story, it made me regret that it didn’t go deeper into the lives of the characters who, by the end, I had a genuine affinity for.