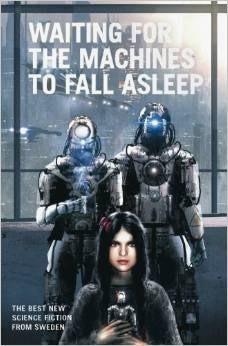

Waiting for the Machines to Fall Asleep

Waiting for the Machines to Fall Asleep

edited by Peter Oberg

(Affront Publishers, May 2015)

Reviewed by Chuck Rothman

I always like the opportunity to read science fiction from places outside the US. You often find authors reinventing the wheel, of course, but you can also find writers whose conception of the genre is more than the usual stuff. So I jumped at the chance to read Waiting for the Machines to Fall Asleep, an anthology of new science fiction from Sweden. None of the authors’ names are familiar, of course, but the exploration is a good part of the journey.

The book begins with “Melody of the Yellow Bard” by Hans Olsson, the story of Rasmus Ekblad, a scientist who has come up with a thesis about controllable wormholes and who is approached by a mysterious company who offers him a mysterious job. He eventually discovers the real goal: a wormhole is being used to take people to other worlds, but lately there have been some problems. The story sets up a situation and a mystery and Rasmus works nicely as a character, but the ending is just a downbeat revelation that hangs in the air.

Boel Bermann contributes “The Rats,” where the narrator is recruited to help solve Sweden’s rat problem. Taking a page from the Pied Piper, he develops a way to lure the rats out of the city, but the narrator has been infected with a disease that makes him empathize with the creatures, and he eventually takes the matter into his own hand. The narrator shows a change in personality – maybe even madness – from his disease. The story does a good job of drawing you down with him, and had an ending that is both disastrous and hopeful.

“Getting to the End” features a hardboiled detective who is asked by a sexy and mysterious woman to find a book. It’s set in a world where “the Event” has changed things, including creating the “Event Sector,” which warps reality in odd ways. Like any hardboiled mystery, things are not as straightforward as they seem. Erik Odeldahl uses some familiar tropes, and a revelation that is hardly original so it really just becomes an exercise in style.

Ingrid Remvall’s “Vegatropolis – City of the Beautiful” follows a couple of young women who crash a party where the beautiful people attend, in a world where there are very advanced AIs who are out to take over by force. It’s a bleak story and very futile overall, though the personality of the main character, Vega, and the description of the situation are almost enough to salvage it.

“Jump to the Left, Jump to the Right” by Love Kölle is set on a different world, where the survivors of a long-ago space expedition have developed their own legends and rites. Norma has to go through a trial – to go into the jungle and kill a beast. The story concentrates on Norma’s adventures on a well-thought-out alien world and how she survives with the help of an old disco song whose lyrics she takes to be instructions.

Lupina Ojala contributes “The Order of Things,” a dystopia where Ida lives on the outskirts of a city, where order has broken down after the robots and machines were destroyed. Her child Linus is in need of medical help, though, and she has to go to extraordinary lengths to save him. This is a familiar idea, but the society and the story are memorable as are the underpinnings that made this all happen. We sympathize with Ida, and the ending has a vivid emotional punch that makes it first-class science fiction.

“To Preserve Humankind” is a different look at the Three Laws of Robotics, where the main character, a robot Maid, tries to come up with a way to protect both the robots and humans. Christina Nordlander comes up with a clever, though horrifying, answer to the dilemma in this short piece, which only presents the idea and ends.

“The Thirteenth Tower” by Pia Lindestrand shows life after a natural disaster, where the seas have overrun the land. Set in a Prague that is now located by the sea, with knowledge of history lost, it’s about a woman, a Swede stuck there and ruminating about how much life has changed. It’s more a poetic description of the situation than a story and I don’t think it’s anything more than nice images and little else.

The only story that has been translated, “Punch Card Horses,” is about Lage, an old farmer, who travels many miles to a market town to buy a new ox. But there are no oxen to be found; the closest things are the “Punch Card Horses” – robot horses running on punch cards and which, the salesman assures him, are even better than the real thing. Lage is skeptical, but has no choice. Alas, the horse is crude and whenever he makes the long journey to the market, the salesman already has a solution – an upgraded version. Jonas Larsson’s story makes it sound like how computers are sold today, and the treadmill turns into tragedy.

“The Philosopher’s Stone” by Tora Greve is an alternate history featuring the great English scientists of the 17th century – Isaac Newton, Robert Boyle, Edmund Halley, et. al – and the German Frederika von Liebnitz. Dr. Isaac Barrow knows the men and is present when they begin to discuss the Philosopher’s stone of the title, which is nothing like the one in alchemy. It’s an interesting exercise, and changing von Liebnitz into a woman helps propel the story to the end.

Andrew Coulthard shows a future world of gaming in “A Sense of Foul Play,” where games have taken a different turn. This talks about the Nordberg Gaming Club, which holds a special game each year to determine who will be named club secretary. Player 3 wants her shot, but the game this year is kept mysterious and, once it is revealed, has a series of very strange rules, set up by an AI. The story becomes a “is this real or simulation?” story. It’s interesting, but the paranoia becomes a little too obvious.

We’re in flash fiction territory with “Waste of Time” by Alexandra Nero, a story built entirely around the title phrase. The narrator is dealing with buckets of timewaste – the moments that people wish they had made more of, and lost. It’s fairly preachy in its effect and pretty much just presents the idea and ends.

“The Damien Factor” has Lucas about to be injected into the mind of a comatose young woman who has been cruelly violated in order to find the criminal. It’s a new experience for him, made more difficult by the Damien factor, where the host mind might overwhelm his own. But there is a darker force involved. Johannes Pinter takes the idea and makes an interesting journey, though the darkness of the ending seems arbitrary

Andrea Grave-Müller serves up an odd sort of fantasy world with “Wishmaster,” where goblins live with humans. Marcus runs into Ella, a female goblin who works in his office as a cleaner, and who is in trouble, having taken a valuable watch from Christina Lorentz, who runs the company. Christina wants it back, even going to a goblin to help her. The watch turns out to be far more valuable than at first thought. The story is fast-moving light fare, with an ending that is something of a nice surprise and stands out from the rest of the book.

“Quadrillennium” by AR Yngve is set in the far future, showing a family gathering together for a traditional solstice ceremony, based on an imperfect knowledge of what the tradition was. The misunderstandings are cleverly portrayed, with a sick and sardonic sense of humor behind it all as various elements are mismatched.

My Bergström ‘s “Mission Accomplished” tells about Lt. Berger, who wakes up confused and disoriented and floating above the moon. She is told of her mission: to evacuate the Lunar base after an enemy has attacked it. But things are not exactly what they seem, even to the people who are in charge. The story slowly reveals the situation, though I found it a bit difficult to feel for the character.

Kitu is a marshal on “The Road,” keeping traffic moving on the major transportation route on another world. She finds two friars, Brod and Klim and helps them on their way. But Kitu sees through their appearance to discover that they have secrets, and offers to help, as we learn she has secrets of her own. Anders Blixt creates a vivid society, and Kitu is an excellent character.

“Lost and Found” by Maria Haskins is about the aftermath of a spaceship crashing on an uninhabited but barely habitable planet. The lone survivor has to learn how to survive in the cold environment, and slowly goes mad. There’s a lot of good description but basically the main character just curls up and dies in response to everything.

I did like Patrik Centerwall‘s “The Publisher’s Reader” a lot. It’s an extrapolation about the publishing industry where Helga is an editor. It’s a real hands-on job: the author sends her pages each day, and she goes over them to make sure they have appropriate content – “appropriate” primarily meaning “what is currently popular.” But a manuscript comes across her desk by a new author, which is brilliantly written, emotionally strong, and completely out of style. But Helga hesitates, even knowing that the entire project may never see light of day. It highlights the problems with the blockbuster mentality and how it leaves us culturally poorer and makes its point deftly and without preaching. Certainly the standout of the book.

“Stories from the Box” is a work of mystery with no real purpose. The protagonist is being kept a prisoner in a box that gives him no room to walk or even stand. But one day, the box opens and he gets out. Everyone is dead and he wanders in the empty world. Björn Engström does not give any explanations or resolutions and the work is just an exercise in futility.

“The Membranes in the Centering Horn” by KG Johansson has a narrator visiting a London club and finding an old man telling him a story about his adventures in the Sudan, where he ended up meeting an alien woman who gives his native bearer a book that supposedly has the answer to all questions. But the book is given to a native guide, and the man’s racism causes him to try to steal the book, losing it except for a single phrase. The story is a lesson in assumptions and the open ending works just fine in this context.

Oskar Källner contributes “One Last Kiss Goodbye,” where a woman goes to the house of an older man, who is shocked and angry to see her. They were married, but she had gone into space and time dilation has taken its toll. This is a strong emotional setting and the problems of the two are both realistic and sad.

“The Mirror Talks” by Sara Kopljar has the narrator buying an android son, but soon finds he has trouble dealing with it. The change from happy acceptance to darkness seems both abrupt and arbitrary and the story really didn’t work for me.

In “Keep Fighting Until the Machines Fall Asleep,” Kate is part of an underground movement to defeat the AI machines who have taken over humanity, and has come up with a way to defeat them using a computer virus. But when they try, their plot is discovered and they are under attack and hope to hold out long enough. Eva Holmquist’s story is reminiscent of the classic Jack Williamson story, “With Folded Hands,” but does not improve on it and the twist in the ending makes you wonder what the entire point of the exercise is.

“Outpost Eleven” by Markus Sköld is a hard sf story about a space station on the edge of a “black cloud,” something that drifts like a cloud, but which no one is sure what it’s made of. Marta commands it, and they begin to experience problems, including the death of some of her crew members, with a presence lurking in corridors. There’s some nice atmosphere, but the story soon devolves into a horror wannabe, with the characters all falling over like bowling pins and a “life’s a bitch” ending.

Anna Jakobsson Lund is the final author, with the story “Messiah 311,” set in a world where everything is falling apart. The main character has been sent back in time to try to prevent it but fails and some version of his keeps trying. It’s just an exercise in poetic gloom.

I was struck by the gloominess and futility that suffuses these stories. There are too many pessimistic views of the future, and two-thirds of the stories end with either the death of the protagonist or of the entire human race. There’s nothing wrong with a bleak vision of the future, but the book has nothing but bleak visons of the future. While a few of the stories (notably “The Order of Everything” and “Punch Card Horses”) manage to achieve true tragedy, most are just pure futility, where the stories just exist to break the characters into little pieces. And over 300 pages of downbeat visions do tend to wear on you. Dystopias are all well and good, but darkness for the sake of darkness does not a good story make. Still, there is enough good work here to make this a strong collection of stories.