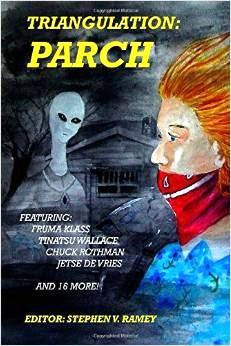

The 2014 Edition of PARSEC Ink’s

Annual Confluence of Speculative Fiction

(2nd edition, September 2014)

Edited by Stephen V. Ramey

Reviewed by Louis West

This is a collection of tales about being parched, not for water, but for purpose, justice, power or life. Many of these stories also include allusions to water, whether too much or not enough.

In “A Prayer at Noon,” by John M. Shade, a girl and her sister scratch out a meager existence, managing their father’s gun shop in a town that stubbornly defies the encroaching desert. Although the girls aren’t blood sisters, they only remember their lives after the man they called Papa rescued them from near death. The girls didn’t know if Papa was a god or not, but he did protect the town from the occasional rogue god that came to cause mischief. They were family, until Papa left for the factories on the other side of the desert and never returned. Then the patchwork man/god arrived, and the town gifted him with things, hoping he would save them. Except, the patchwork man takes the younger sister, declaring she is his reason for existence. Now the older sister has to leave all that she knows to rescue the only family she has.

This quick-paced tale is filled with people desperate for purpose yet spiced with the hope of something different for the sisters at the end. An enjoyable read.

In Jacob Edwards’ “Koan,” Koan has led a sheltered existence, living out of his one-room apartment buried deep under the supposedly lifeless surface, commuting with his personal T-mat device. The day water poured through his ceiling, flooding his place and destroying his T-mat, ended that. Now all he has is a view of a bright spot high above, through all the intervening apartments that should have been occupied but were unaccountably vacant. Then he hears a chirp, and thirst for freedom beckons. Sometimes we have to lose it all to recognize what else there is that can be so much better. A quick, fun read.

In “Passages,” by Jacques Barbéri, a young boy, Jermy, visits Plexiglas-protected ancient books and finds the holos of the book contents beautiful. Thirty years later, he discovers how to break into the high security museum and actually handle and read the books. In his greed, though, he exposes the books to the elements, destroying them. There is nothing about being hungry for knowledge that yields rational actions.

Madhvi Ramani’s “Noah” portrays a post-flood Noah racked by doubts and guilt. Through the haze of his escape into wine, he vaguely recalls breaking down during the horror of the flood itself. Now the wine is gone and, until the new crop ferments, he suffers withdrawal, paranoid about what he thinks his extended family is saying behind his back. He finally decides that no one respects him anymore. In a fit of rage, he reasserts his sense of empowerment by raping his grandson, Cannan. While there are legions of possible religious ramifications from this story, I found the ending way too dark and twisted for me.

In “Dust Storm,” by Chuck Rothman, Belinda silently suffers the never-ending dust storms of 1930s Kansas, the abuse from her alcoholic husband and the indifference she feels for her scrawny child, Earl. Ever since the death of her daughter, Dolores, and the onset of the storms, all meaning seems to have fled her life. After an alien crash lands in her yard, she rescues him, but her husband kills the alien thinking he’s Belinda’s lover. Then the alien’s mother comes looking for her dead son. In this grief-wrought being, Belinda finally recognizes her own grief and loss, enough to harden her resolve to change it all. I rejoiced at Belinda’s rebirth into a person of purpose. A good read.

In Diane Turnshek’s “Vegan,” a Godzilla-like creature, a mother laden with ready to hatch newborns, leaves her mountain home determined to find a place where she can feed without hearing the mental sorrow of her sentient prey. She ventures to the lowlands and discovers large (nearly a mouthful each) “insect-like” creatures that walk on two legs and fight her when she tries to eat them. But they’re not sentient, for she hears nothing from their minds as they die. Joyfully, she decides to settle here and teach her young to husband this new crop of food. One could conclude that these “insects” are humans and our understanding of what constitutes “sentient” is horribly wrong. But then, that’s up to the reader to decide. Deliciously entertaining. Definitely recommended.

“Dream Warriors: Ramayan Redux,” by Rochelle Potkar, requires a lot of careful reading unless you already possess a detailed understanding of Indian Ramayan mythology. It’s a story about justice for the dispossessed, especially women of Indian society who still suffer in silence for outrageous abuse, discrimination, and “honor” killings. But the veil of silence is falling. This tale follows detective Kapeesh as he searches for a woman missing for six months. It blends his real-world search with deep-sleep dreams filled with characters and imagery from the Ramayan epics. A different yet deeply substantive tale. Recommended.

Kenneth B. Chiacchia’s “The Well” is a hard SF tale set on an alien planet liberally spiced with religious conflicts over ancient artifacts, a spy thriller and smuggling adventures gone bad. Sergei’s a translator, banished to a provincial second city and diplomatic backwater for unnamed sins. Now he’s involved in efforts to smuggle an alien religious artifact off-world to a buyer, all to raise funds for a well for a water-starved native village. The deal, of course, goes sour. Now he has to survive involvement by gray-man elements of the Spacearm’s dirty-tricks branch, an alien military contingent there for purposes of “business” and capture by a fanatical native warlord who will do anything to possess the artifact. Rescue comes in the improbable form of a gaunt, old native shaman who appears to Sergei out of thin air. But, it’s only when Sergei realizes that the shaman has put multiple counterfeits of the religious artifact into circulation that he sees his way to escape the carnage swirling around him and secure the water well that had gotten him into trouble in the first place. Wonderfully complex. Definitely recommended.

“Floorboards,” by Christopher Nadeau, is a horror tale about a man tortured by his need to keep his demon-spawn children alive, all while desperately wishing he had the resolve to end it all. The ending was obvious from the beginning.

John A. Frochio’s “A Fine Selection of Wines and Poisons” is a tale about a butler mad with aspirations for world domination, triggered by hosting nanotech that turned his body into a poison antidote factory. Crosstime detective Emile is drawn to the crime site of the poisoning of Sir Talbot Cabot. By using clues he or other agents already planted, he deduces that the butler did it. Lots of exposition and just plain telling with no real tension.

“The Straw-Mother,” by Jamie Lackey, is a short tale about a woman made of straw and burlap. Only the spring rains refresh her. In between, she diligently performs all the drudgery of cooking, cleaning and housekeeping, until sparks catch on her arms from the oven, and she becomes afraid. Only waiting for the rain gives her any hope. A poignant allegory for the rigid roles women are expected to fill in many cultures and times. Recommended.

Tinatsu Wallace’s “Smitten” is about forced love and jealousy. Simone had been in love with her husband, made that way by a series of injections. Now the effects have worn off, and she hates how she feels. Her doctor describes it as a “rough patch,” but agrees to give her a new injection of “love juice.” While waiting for the drugs to change her, she confides in her sister who’s just been dumped by her married boyfriend. Her sister advises that Simone can’t keep drugging herself because “the heart wants what the heart wants.” When she gets home, she discovers that her sister had just had sex with her husband. However, overwhelmed by the hormonal flood from her drugs, she ignores her husband’s physical abuse and kisses him until they end up in bed. Perhaps this is an allegory for women who endure abusive relationships, but I didn’t find the tale compelling.

“Parched in Purnululu,” by Jetse de Vries, is a survival story told by an old frog, Sally, to the young ones too busy enjoying the bounty of the wet season to be concerned about providing for themselves once the dry times come. Throughout the tale, scenes flip between talk about geologic events and Sally’s unfolding tragic life. Didn’t get this one at all.

Julia August’s “Bitter Water” is a tale about the impetuous folly of young men who are thwarted time and again by the intricate machinations of “barbarians” who first raid their caravan, then rescue them. Arion is a recently manumitted slave. His master’s father has often traded quite profitably with the powerful peoples of the desert, so Arion, his master and some friends seek to run a caravan themselves. After being left for dead in the desert by raiders, they’re rescued by a relative to the Tekel Great King. While Arion’s master recovers from extensive wounds, Arion tries to figure out how to regain the stolen caravan goods. However, the Tekel clan culture is rife with intricate family and cousin relationships, and Arion’s rescuers seem more amused than serious about his concerns. Arion forces a meeting with a cousin to the King he thinks knows both the raiders and where the caravan goods are being kept. He eventually finds the raiders, but they pitch him into the desert because he can’t pay what they ask to get the goods back. This time, he’s saved by the subtle, lethal humor of desert peoples who think themselves great jokers. Deliciously twisted and definitely recommended.

In “Mask of Sleep,” by Rosemary Bensko, a man is punished for a horrific crime by being confined in a mask that prevents him from seeing, drinking or eating, forcing him to ponder his sins and all those that had died because of his folly. However, the first and second sentences were so atrociously constructed that I immediately lost interest: “… as the mask’s eyes droop into the last increment in the horrible progression of a month toward closure. It sleeps in wood, paint peeling off the edges of the visible world.” Huh?

Kaitlin McCloughan’s “The Hope of a Thirsty Planet” is space opera about people of a drought-ravaged world trying to secretively colonize a terraformed Mars. To accomplish this, they’ve raised Lin, one of their own, from childhood on Earth, gotten her into the astronaut program and outfitted her with the components of a bomb to destroy a deep-space monitoring station on Mars, thereby allowing a secret invasion fleet to approach. But Lin wimps out at the end. The story reads like a badly written YA tale with shallow, unrealistic characters, simplistic plot and 20th century technology, even though Earth has terraformed a planet and colonized the stars. A definite pass.

“Before Bastrop,” by Michael Collins, is a post-apocalyptic tale about how much people are willing to endure just to get a drink of scarce water. A linear plot without any insightful twists.

In Jen White’s “Shuttle Season,” Drayer is a shuttle rider, running supplies back and forth to the moon before returning to the shuttle base in the Australian outback. Budget cuts have compromised maintenance; consequently, on his latest return trip, his aging ship encountered some kind of energy barrier and duplicated him. (The mechanism of this event is unexplained.) He returns home to his family, before the “other” of him can arrive, to reassure them (and himself) that he is the real Drayer. But doubts abound, both in his mind as well as his family’s. Several days later, he evaporates.

The premise of this story isn’t new: a Star Trek episode also had Captain Kirk duplicates vying for dominance over each other. While this story could have explored new ground regarding who is the real “original,” such as “yes, both of them,” it just rehashed the old. Disappointing.

In “A Long-Forgotten Memory,” by Elizabeth Spencer, an ancient memory AI, Alucia, has stood guard over a long-forgotten mage city abandoned over 15 centuries ago when the water ran out. Now new peoples come in a steam and magic-powered airship. Alucia is eager to learn everything she can from these newcomers, but they refuse to talk with her. In her desperation, she disables their ship, dooming them to die from lack of water. But now they have no choice but to talk with her. The moral: Never piss off an AI hungry for new knowledge. A nice twist to the end. Recommended.

Fruma Klass’ “The Way We Were” is a tale about aging were-creatures, living out their final days at the Bide-A-Wee Home for the Aged and Wery. They pass their time talking about the old days, until local townfolk learn of their presence and mount a vigilante protest. Looking to be accepted as just another minority wanting to be left alone to live in quiet peace, the were-folk mount their own offensive, but not one of violence. A cute tale. Recommended.

Louis West. Sub-atomic physics, astronomy, biophysics, medical genetics and international finance all lurk in Louis’ background. He’s fond of hard SF, writes reviews for a variety of Speculative Fiction publications and volunteers at several New England SF&F conferences. As an Author-in-progress, his SF writing embraces both Nanopunk and Biopunk genres.