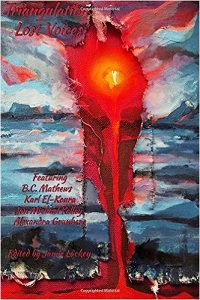

The 2015 Edition of Parsec Ink’s

Annual Confluence of Speculative Fiction anthology

(July 2015, tpb, 160 pp.)

Edited by Jamie Lackey

Reviewed by Harlen Bayha

Triangulation: Lost Voices turned out far better than it appears from the title or looks on the cover. Most of the stories in this volume follow the “lost voices” formula fairly closely, with someone or some thing losing the capacity to communicate. This focus yielded a fantastic crop of heartfelt, thoughtful stories, including several highly recommended pieces.

“Loss of a Second” by B. C. Matthews starts off with a simple premise, but eventually blossoms into a powerful examination of the meaning of self, the meaning of friendship, and the meaning of love. Miranda-Nym lived together in the same body, each a second to the other. Nearly everyone has a second, each taking primacy when necessary or desirable. They have different skills, hobbies, and tastes, but when one is lost, what does that mean? Miranda must deal with the consequences now that Nym has inexplicably gone silent.

What does that mean for Miranda’s friends? How do they grieve? Should Miranda consider going to support groups for her loss? What does it mean that she hates herself without her second? Where can she go to evade the social stigma of being a single mind in a world full of pairs?

In a way, this is an allegory about relying too much on someone and losing yourself, but it’s also about simple wisdom and resilience. Highly recommended.

“Passing Through” by Alexandra Grunberg has a prosaic, meditative feel. It’s about life after death, and not in the usual light in the tunnel, zombies eating heads, or vampires clawing up out of a grave sort of way. It’s more of a secular afterlife, a quiet fading away. Short, but good.

“A School Report on My Great-Grandad, a Retired Superhero” by Karl El-Koura has some awkwardness in execution, but the overall concept is so charmingly heroic that a reader may let those misdemeanors slide. The story’s an interview report written by a sixth grader. At times the report is too childish and other times too adult, but it does provide a few chuckles when the inconsistencies appear, and there’s perhaps a scientific reason for this precociousness.

The narrator spent a frustrating afternoon with his retired-superhero great-grandfather, Sam Twyson, who (despite being in miraculously good health) appears strangely unable to focus and refuses to answer questions with straight talk. However, reading between the lines, which the narrator cannot, perhaps due to his age and inexperience, we get a good feel for what has happened to Sam as his powers became renowned and the public started to demand more and more of him. He eventually let his voice and his presence fade into the background, and now takes his retirement, but there remain hints that all is not as it seems.

“The First and Second Offerings” by H. L. Fullerton examines what might happen should we breach the boundaries of communication between humans and our furry forest friends. Vivie is an attorney with a tree-hugging boyfriend, Sky. Sky goes crazy, gets violent, and has to be locked up, but Vivie starts to sense there’s more to those events than one psycho ex-boyfriend can explain. The animals Sky claimed plagued him seem to be taking a liking for Vivie now, and she seems to have a way with them as well. Recommended for spooky animals, awkward relationships, and a wicked last line.

“The Bear-Woman of the North” by Rebecca Harwell seems to be about a woman who used to be a bear, but the true story really revolves around her friendship with an American slave, Julian, who befriends her. Because it’s told through the eyes of the bear-woman, issues like love, abuse, and slavery require the reader to add many details and guesses from their own imagination, but unfortunately, the bear-woman’s perspective provides little in the way of clues to work with. It’s a good try, but the bear-woman’s story seems to detract from Julian’s instead of augmenting it.

In “Sea Queen, Sailor Queen” by Melissa Mead, Liaula the siren battles Captain Tethys, a woman who captains a ship in a male-dominated society. Tethys captures Liaula, and makes a deal with her. This deal goes wrong for both of them. Liaula gets presented to Tethys’s king, who doesn’t know what he’s got and places her in a menagerie with other oddities, all of which are animals but her. Tethys, for her part, gets the shaft and loses her command. Once the dust settles and Tethys realizes how little she is valued, they become unlikely allies and take to the seas once again. For an action story, the pacing felt a little off, and the critical lies Liaula tells herself at the end felt out of character.

In “Wandering Swallows” by Jennifer Crow, a starving North Korean boy on the run captures a bird to eat, but is himself captured by a guard. The man claims to be his father, and to have watched him in the prison camp where he grew up. This awkward relationship morphs into a gruesome modern folk tale as imagined on behalf of one of the last angry, separatist states. There are points where it avoids a logical, if homicidal, solution to the problem of obtaining food, but its creepy, dark tone and unique situations give this story wings. Recommended.

“Moving Metal” by Joann Oh animates a man made of twists of wire and clockwork. As Amanda tries to figure out where he came from, she becomes enamored of the expertise of his manufacture and the bizarre fortune-cookie sayings that spout from his mouth. She names him Daniel. The only problem is that Daniel never meant any of the written words he purportedly “said.” His feelings are far more complex and varied, but he cannot speak, and his animatronics are not adept enough to allow him to communicate precisely.

Amanda takes him home and tries to assimilate him into the world, showing him to her boyfriend and taking him out to do things with them. The twists of wire and faux-Confucian slips of communication eventually betray them both. Engaging, but rather sad.

In “Not All Their Own” by Erin Cole, Lyssa’s fisherman husband, Devlin, dies at sea. Lyssa brings him back with a sacrifice, but when he walks out of the surf, it’s evident that he’s “not the same” (Lyssa’s surprised at this because apparently she never rented Pet Sematary). Lyssa and her friends all end up having to do this because their men, who are also fishermen, also die at sea. When they come back they’re all “not the same.”

However, since the reader never sees Devlin before his disappearance, and since nothing truly weird happens after his recovery, the story lacks the actual horror of having something actually go wrong. The vague feeling of disquiet and the sacrifice of animals by the women never rise to the level of horror as promised by the setup.

The story’s antique message appears to be that emotionally distraught women cannot get along alone and have no means of taking care of themselves or their families without a man. Not only that, but any man will do, even a creepy undead man, a noxious message that many real-world women have justifiably fought against for decades.

In “Pacific Standard” by Anita Dolman, Claire works in a hospice where she falls in love with a patient who cannot move or speak. It’s not quite as wrong as it sounds, since Claire’s comatose beaux is able to communicate with her. She has a psychic ability to speak to the near-dead. Fortunately, she’s not crazy: the other hospice workers acknowledge her freaky tendency to communicate with other voiceless patients as well. Because of her ability, Claire’s a lonely sort who really wants to reach out to people, but has limited choices on how to do so.

The story’s well-constructed ending is bitter, with a side of extra-bitter, and a dash of sweet. Highly recommended.

“The Dragoon of the Order of Montesa, or the Proper Assessment of History” by Sue Burke isn’t really a story, it’s more a humorous deconstruction of archaeology and anthropology. It’s a farce created for everyone who’s ever heard a talk on the habits of ancient people as imagined based on the implements found in a pre-historic trash heap or grave, anyone who has thought “How did they ever come to such sweeping conclusions from a few scraps of trash and some petrified feces?”

If you’ve ever sat in a class wondering how they concluded all ancient humans had particular habits, diets, and social structures from the way a few chips of stone were hewn or the carvings on someone’s thunder mug, you’ll appreciate this delicious sendup of pseudoscience.

“By Way of Answer” by Sean Jones is another of several bird-themed stories in this anthology. It’s a first person tale of a quest for revenge against a Comanche raiding party by the last survivor of a small village of viking descendants living in North America. Uldayn’s world is filled with animist magic, a combination of Norse and Diné (Navajo) influences. The tale and action is engaging, but this story could have focused on the son of any pre-colonial nation. Uldayn’s Norse-ness doesn’t actually affect the outcome of the story, except for his mysterious talking crow, which would have worked fine with any totemic or animist culture. Since a man of any nation could have filled this role and subtracted not at all from the story, and since the author took pains to treat the Comanche and Diné with respect, it leaves one to ponder, why did the hero have to be a white guy?

The protagonist, David Lewitt, feels like a proper mysterious friend in “The Frykstadbanan” by Michael Nayak. This energetic and mysterious young-adult story brings together rural Sweden, a globe-trotting hero with mysterious powers, ominous and villainous creatures, and a simple but sweet love story.

Unfortunately, some logic issues might throw off some readers. This would be a less bothersome story if it was dated in the 1960s or 70s, but while the time period of the story is unclear, it definitely occurs after Sweden joins the European Union in 1995, and possibly as recently as 1999, the year of the creation of the eurozone. Therefore, a modern reader must question why David hasn’t tried two very simple solutions to his problems: phones and the internet. He doesn’t seem interested in calling his hometown authorities or finding his family, even though he left them accidentally only four years prior, and there’s no indication they aren’t looking for him every day. These days, they’re only a trip to Google and a phone call away.

Still, there’s an undeniable emotional resonance to this story: David’s visceral sense of confusion when he falls through cracks in reality to new locations, his need for human companionship, the way he falls for his benefactor’s daughter as they stay up all night reading or looking at the stars. It harkens back to an earlier time, when a kid in trouble might have wild adventures, and the world was not as small and close-knit as it is today. Despite some plot holes, highly recommended.

“Matryoshka” by J. J. Roth takes an analogy and makes it magically real. Dolores finds a toymaker who can take her apart and remove her shells like a Russian nesting doll, each time removing more and more pain from her boring, sad little life. It’s a story trying to be sad and deliver meaning, but without first establishing the main character as interesting enough to care about. At the end, the inevitable happens.

“Empty Reception” by Vincent Baverso is a forgettable story about two astronauts, Rosewater and Lavcifka, who decide to abandon their space station and return home after an atmospheric event devastates the earth.

“Offering” by Kathryn Yelinek centers on a young narrator (probably male) who is scared to death of a copse of apple trees on his family’s land that his mother swears is full of ghosts. Confronting those fears, he goes out at night to do some stargazing, but gets treated to a ghastly surprise instead, one that will not let him go. Fortunately, he has resources to solve his problem: a wise local librarian, his own creativity, and the Google. Another bird story in this anthology, but one of the best.

“The Ghost of Arriscado Basin” by Jon Michael Kelley feels like a Platonic dialogue, with much philosophizing and explaining by one wise-appearing party who has little or no science to prove his claims, and with polite noises made by the young people who have come to him for answers. The entire story feels like exposition that might lead to a larger adventure, but the pedantic exercise seems to miss the main emotional driver: that the young boys were out in a jungle observing monkeys and came across something terrifying. That terror, the vivid emotions of seeing something horrible that cannot be explained, is undercut by sharing that discovery in the most antiseptic way possible.

“Nature Could Not With His Art Compare” by Leigh Harlen comes and goes quickly, attempting to surprise or horrify by putting the reader in the mind of a statue come to life.

Anik discovers a beast of myth in “Aurora Borealis” by John Walters, and decides to risk her life to save it from a trapper who would likely kill it for fame and fortune. While on the run, she discovers that she has more in common with this myth than she could have imagined. Anik’s story bears some similarity to the earlier story, “The Bear-Woman of the North,” both in theme and setting, but “Aurora Borealis” has more impact.

“Opportune” by Paul Abbamondi tells the story of ships imbued with life, forced to do the bidding of the wizards who constructed them and now ready to rebel. A short, snappy tale of what it means to be self-aware, but unable to speak.

“Love at the End of the World” by Frank Oreto gets off to an awkward start, but ends beautifully. Vincent is a professor who bid farewell to his partner, Alex, years ago because Alex was convinced ghosts were coming to destroy the world. In the years since, Alex has developed a following of believers, and has taken to shouting from the watchtowers (via online media and television) that a dead race of beings from many light-years away has just died when their star went nova and they are racing toward Earth. He and others claim to have already experienced the bodily possession caused by encountering these beings.

Vincent couldn’t take Alex’s crazy when he was younger, but when Alex comes back into his life, Vincent realizes there’s a difference between his perception of what Alex does and who Alex really is. The story is about overcoming blindness and accepting things you may not understand, things that don’t fit into established formulae or rules, because they are true, and their truth is undeniable. It’s also about allowing ourselves to hear the voices that may have been lost to us as we age and forget to listen: the voices of love, courage, and imagination. A fitting thematic ending to the Triangulation: Lost Voices anthology.

Harlen Bayha gets more funny looks in a single day than most people get in a lifetime. Reading his fiction could make you get funny looks too, but no promises.

Triangulation: Lost Voices

Triangulation: Lost Voices