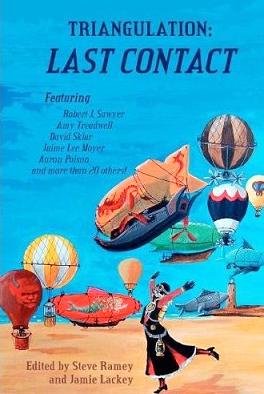

Edited by Steve Ramey & Jamie Lackey

(Parsec Ink, July 2011)

“A Claw from the Western Paradise” by Gwendolyn Clare

“The Good Daughter” by Aaron Polson

“Ghost Horses and Dream Dogs” by Shanna Germain

“The Gold in the Straw” by Amanda C. Davis

“The Bright Air That Breathes No Pain” by Eric Schaller

“Boll Weevil” by Nathaniel Lee

“The Customs Shed” by John Walters

“Ezekiel” by Desmond Warzel

“Ocean Daughters” by Jaime Lee Moyer

“City of Bones” by Deborah Walker

“In Ruins” by J. M. Odell

“In the Shadow of God, There is Fire” by Sandra M. Odell

“Lord God Bird” by Sarah Frost

“Norms” by Cynthia Ward

“To Rule, Do Nothing” T. F. Davenport

“Zafir, the Saudi Superhero” by Madhvi Ramani

“Twilight’s Last Gleaming” by H. L. Fullerton

“A Lack of Charity” by James Beamon

“To Give the Perfect Dewdrop” by Dawn Lloyd

“The Party” by Christopher Nadeau

“The Reel” by H. M. Tanzen

“The Last Cyborg” by M. Yang .

“A Feast of Kings” by David Sklar

“The Charnel Pit” by Stephen Gaskell

“God in the Machine” by Charles Patrick Brownson

“Seedling” by Eric Zivovic

“The Loss of Pain” by Amy Treadwell

“Mikeys” by Robert J. Sawyer (reprint, not reviewed)

Reviewed by Chuck Rothman

Triangulation is a series of loose-themed sf/fantasy anthologies put out in conjunction with the Confluence SF convention in Pittsburgh. This year’s edition uses the theme of “Last Contact,” and leaves it up to the writer to determine what “last contact” means. The result is a first-class anthology of 27 original stories (and one reprint) that will please any reader of speculative fiction.

The book starts out with “A Claw from the Western Paradise” by Gwendolyn Clare, about Ao Jun, the last of the dragons, who is charged with guarding the bones of his kind. A human approaches and wants to trade for a dragon’s claw, but Ao Jun is not inclined to help him. I liked the idea of the last dragon, but overall, the story didn’t really catch fire, and the solution should not have taken so long to arrive at. Not a bad story, by any means, but not a strong beginning

“The Good Daughter” by Aaron Polson starts out with a great opening: “While Evie labored at her morning chores, she dreamed of crushing her sister’s skull.” Evie lives on a colony planet, angry and resentful that her parents force her to work hard at chores, while her sister Lainie is treated like a princess, and pampered all her life, never having to lift a finger. Eventually Evie discovers that things aren’t what they seem. I liked the story a lot, finding it emotionally powerful despite the fact that there is plenty to nitpick (I’m not sure why Evie’s parents take so long to tell her what’s going on). But the ending works very well, and the revealing of the situation is very satisfying.

Shanna Germain‘s “Ghost Horses and Dream Dogs” features Dale, a former jockey in a time when horses are extinct. Dale is extremely old (I get the impression some sort of life extension technology is involved) and has to have his memories wiped (probably to make room for new ones). But he has kept the memories of the horses and races; when a new overwriter comes by, he may have to give them up. I found the story a bit vague in what it was trying to say and too much was left unanswered.

“The Gold in the Straw” is a retelling of the Rumpelstiltskin legend, told from the princess’s point of view, and her attempts to figure out Rumplestitskin’s name. Amanda C Davis has an interesting take on the story with a decent twist at the end.

“The Bright Air That Breathes No Pain” is one of the few duds in the collection. As a schoolboy, Todd was taken aside by a mysterious girl and told to dig a hole. He leaves despite her urging to finish and regrets it. Years later, he starts becoming restless with his marriage and begins thinking about the girl. Eric Schaller makes reference to several businesses that are local to me and, to be frank, the main reason I kept reading was to see if he lived nearby (he doesn’t). Todd’s longing for the girl is never adequately explained and the ending falls into a pitfall inherent in the anthology’s theme — it’s futility, not tragedy.

I was also disappointed in the futility of Nathaniel Lee‘s “Boll Weevil.” It’s a short short about an invasion of mysterious bugs — like boll weevils, but feeding on everything they can find. I love the voice and the character of Jess, but did not like the futile ending. Jess basically just gives up and dies. I don’t ask for a happy ending, but it’s not tragedy if the character isn’t trying to do something about the situation other than just giving up. I really wanted this story to be better.

“The Customs Shed” has a somewhat mundane title for an idea that is far from it, but the execution is lacking. I don’t care much for stories where the characters are wandering around wondering whether they’re dead or not, and that’s what John Walters is doing. Martin is wandering, looking for a way to cross the river and learns he has to go through the customs shed where horrible things happen. The ending is pretty much what is expected.

The anthology picks up with “Ezekiel” by Desmond Warzel, a story of what really happened to the “Roanoack” colony in Virgina. It’s in the form of an account written by Ananias Dare, father of Virginia, who becomes the colony leader and meets with the Croatan Indians, who warn him of mysterious doings on the mainland. Ananias goes to explore and discovers, basically, a version of the Iron Giant. This is an old-fashioned SF story — in the best possible sense — with good characterization and a very good feel for the period. The account truly seems to have been written by a man of the time and Warzel deserves credit for giving the story that extra level of verisimilitude.

Jaime Lee Moyer follows up to with a tale of love and the sea with “Ocean’s Daughters.” It’s about Lina, whose husband Ilya is a fisherman who was lost at sea. She tries to ask the sea to give him back. As usual, there is a catch, but it was unusual with the way Moyer takes the tale away from what you expect and into new territory. Lina learns about the price to get him back, and her decision at the end is emotionally right and a triumph for the character.

“City of Bones” by Deborah Walker is an old theme that’s not given enough to make it stand out. It’s about a group of immortals who don their old human bodies to visit the ruins of Earth. In a way, it’s a sequel in concept to Kurt Vonnegut’s “Unready to Wear,” set centuries later. I didn’t find the characters all that interesting — they’re clichéd, bored, and decadent immortals and, of course, the ending it precisely what you guess from the beginning.

J. M. Odell takes an overlooked monster — mummies — and fashions the entertaining “In Ruins.” It’s a terrific story, mostly because she comes up with a “why didn’t I think of that?” concept. Zahur is one of several mummies who have spent millennia buried with their pharaoh, protecting his grave, and unable to move on due to vengeance from the man who had been their foreman. They are roused to action when the tomb is discovered by archaeologists: “If they get in, we’ll be infested for months.” The story is filled with some entertaining and funny characterization, but doesn’t miss the opportunity for drama and an emotionally perfect ending. One of the best in the book.

Alban Hausmann is surprisingly calm when his housekeeper Rita shatters a $900,000 Ming vase, docking her pay $20 as punishment. Hausmann is a fascinating character in Sandra M. Odell‘s “In the Shadow of God, There is Fire,” but the story is about Rita, who needs the job desperately. She discovers a ghost in Hausmann’s house and begins to regret helping him. It’s a good story, though in some ways I wish it was more about Hausmann, since so much about him is mysterious.

“Lord God Bird” is an alternate world story that postulates a group of people traveling from alternate world to alternate world trying to find one where the ivory-billed woodpecker is not extinct and bring it back. Author Sarah Frost clearly likes the idea, but it seems like something that’d be pretty far down the checklist of what to do when visiting an alternate world. I don’t care much for the ending, which is gratuitously nasty, and seems pretty far-fetched even given the situation for things to work out the way they do.

Cynthia Ward‘s “Norms” deals with the age-old question, “What does it mean to be human?” Din and her friends are the “Norms” of the title — normal human beings — in a world where they are slowly being displaced by the “Jennies.” The Jennies are genetically engineered or perhaps even aliens who come in a variety of shapes and colors, with desires that Din cannot understand. It’s a nicely drawn future and the Jennies are all very imaginatively created and the ending has a touch of true tragedy, as Din makes a choice and has to suffer the consequences.

“To Rule, Do Nothing” by T. F. Davenport is a step down. It’s a pretty inconsequential short short story about Kandel, who seems to have slow-poisoned the Queen of the Eight Worlds and now lives on a moon alone, fielding threats and entreaties about providing an antidote. There’s not much else there and Kandel is too sketchy a character to be interesting. At most, this is an outline for a story, but there’s little else.

“Zafir, the Saudi Superhero” is by far the most intriguing title in the book. Zafir is a boy living in Saudi Arabia who loves American comic books and, after seeing the Muttaween (religious police) let his sister die in a fire because she was improperly dressed, starts believing he has super powers, which he uses to harass the Muttaween. It’s a great look at the culture clash between Saudi Arabia and the US, and Zafir’s feats are all right on the mark. I was confused, however, by the ending. I’m not sure what author Madhvi Ramani was getting at, nor whether it was meant to be figurative or literal, and thus triumph or just another futile gesture.

H. L. Fullerton is next, with “Twilight’s Last Gleaming,” in which the resolution of Cyril M Kornbluth’s “The Marching Morons” is told from the title characters’ point of view. Not that the characters are morons, but it is clear that they don’t see what’s going on, even when they lay the entire situation out in their conversations. In the story, Bethany goes out to watch the fireworks, which are spaceships used to escape Earth. Trouble is, only a handful of spaceships manage to escape, and most explode on liftoff, creating the fireworks. Why people are willing to take their chances and why no one sees through the whole situation is never really made clear. Maybe I’m too risk-averse, but I can’t imagine people lining up to get into space when the odds are so bad. “The Marching Morons” is certainly a flawed work (both morally and by the fact that it solves its problem by doing something that is specifically declared impossible at the start of the story), but what made it a classic was the society it portrayed, and this is barely touched upon.

I didn’t much care for “A Lack of Charity” by James Beamon. It’s an ugly story about revenge, that leaves a bad taste in my mouth. Will is searching for Chainer, who raped and murdered his wife, so he makes a deal with a demon to find him. Trouble is, the demon can’t be trusted and Will is led from one Chainer to another, killing them as gruesomely as possible — only to discover it’s the wrong man. You’d think that Will would catch on, but he still continues. So, really, what’s the point? Life is ugly? Vengeance is empty? If so, why tell the reader when Will can’t even see he’s being played.

Dawn Lloyd‘s “To Give the Perfect Dewdrop” seems to be a metaphor for worship and the pitfalls of it. The narrator spends his or her time trying to find the perfect dewdrop to offer to a higher being. No points for guessing what happens when it succeeds. The story works best as a metaphor for religion, but ultimately it’s trifling.

“The Party” is another “Am I dead or not?” story, though it’s pretty clear that Curt is (This type of story only has two possible answers, and to actually have a story, then the answer has to be “yes”). He’s at an endless party, going around, meeting and interacting with strangers. The “cocktail party hell” trope was probably tired by the 1950s, and Christopher Nadeau does not make you long for its return. It’s also voluminously unclear.

Things start improving with “The Reel,” the story of a supernatural being who gains insight as she lives as a human. The idea isn’t new, but H. M. Tanzen keeps it just interesting enough to make the story work. And while the ending isn’t the soaring affirmation it’s meant to be, it’s good enough.

M. Yang (and I’m surprised at the high number of authors here who use initials) manages to deal with loss and hope in his story, “The Last Cyborg.” It’s about Randy Ennis, who created high-tech implants to keep his body young and healthy. Trouble is, the implants work too well, and the organs become semi-sentient, overwhelming people and killing them. It’s many years later, and Randy is one of the last people with the implants. He took them off the market and now just waits for them to fail. But others might be able to do things right, and Randy is implored to let others in on his secrets. I think there are some flaws in the story, but it works quite well despite them.

“A Feast of Kings” is an excellent mood piece with Egyptian gods living in New York City. The story is weird, to say the least, but in a good way. David Sklar creates something of an epic battle as the main character is challenged, though I felt that once you got past the mood, the story was so-so.

We then travel to southeast Asia for “The Charnel Pit” by Stephen Gaskell. It’s the story of Thanh, who is surprised he has been named a pallbearer at the Emperor’s funeral. Similar in theme to “In Ruins” in this anthology, Thanh is not put into the grave to guard, but rather to make sure all who know its location and its treasure are dead. His ghost, though, has unfinished business: to make sure his wife and newborn son can live comfortably without him. It’s an excellent story, nicely plotted, with very strong characters and is one of the high points of the anthology.

However, for me, the best story is Charles Patrick Brownson‘s “God in the Machine,” something of a gonzo alternate history where the English Inquisition has already executed Darwin for heresy, clockwork computers get viruses with religious propaganda, time-traveling dirigibles visit other universes, and one of its top scientists is an intelligent marmot. Abagale is in the Tower of London for heresy, but tries to plot her escape. I loved every minute reading it and it is definitely the standout story.

So it was a real letdown to see “Seedling,” in which a sentient satellite crashes to earth. There’s very little to it, and author Eric Zivovic seems to think that the story only consists of the idea. The final line is nice, but doesn’t make this into a story.

The final new story (the last story in the collection is a Rob Sawyer reprint) is a fine piece of historical drama, but seems to have very little fantasy element. “The Loss of Pain” is about Sir Bernard, one of the Knights Templar during the crusades, who is struck with the dreaded diagnosis of leprosy and goes into a leprasarium to be warehoused until he dies. But the moors are on the march and soon the hospital and castle that houses is it besieged. Amy Treadwell gets the background and feeling right, and raises some interesting questions.

This is overall a first-class anthology (you may like it better than I did if futility doesn’t bother you). The stories are all well-written and generally good reads and this certainly stands out as a book well worth owning.